Everywhere Antennas, by Julie Delporte. This is Delporte's first major work of fiction after publishing the visually-similar book Journal with Koyama Press. Delporte's open-page layouts, use of colored pencils and cursive script create an almost uncomfortably intimate atmosphere as a young woman documents her increasing inability to cope with the world. In the course of the story, we learn that she apparently has a heightened sensitivity to the sort of highly concentrated electromagnetic energy that one might see in modern, urban life. As the book goes on, the young woman (named Lily) desperately finds herself withdrawing more and more from society in a series of stopgap attempts to create a life separated from technology. The more she stays in someone's cabin for a couple of months or hops from couch to couch, the more she feels a variety of conflicting emotions. The headaches, exhaustion, confusion and burning sensation she felt at the height of her sensitivity all ebbed (though didn't completely disappear) as she avoided technology, but that was offset by the feeling of being an outcast.

There's another level of narrative at work here beyond what Lily describes. This book is about the narratives, experiences and observations of women and the ways in which those experiences are ignored and discounted by men in authority. In particular, her anxiety is at first barely tolerated and later dismissed by her then-boyfriend and the doctors she sees, whose response each time is to prescribe a different antidepressant. Her father doesn't question her on her problems only because he doesn't want his daughter to comment on his alcoholism. Her desperate need for connection and for people to believe her reduced her to desperate codependence at first, something that she leaves behind as she starts to leave behind the other constrictions of society. While the end has no real solutions in sight for her affliction, she at least is in control of her own fate and own decisions. Delporte's use of colors is disorienting in a way that's meant to reflect her own increasing sense of alienation in her own environment. That alienation is something she has to cope with, understanding that the very forces she tried to cling to early in the book were literally killing her and driving her insane.

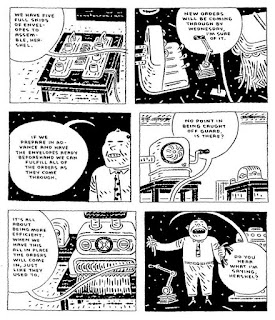

The Envelope Manufacturer, by Chris Oliveros. In the early days of his former publishing concern, Oliveros contributed to the D&Q anthology and also published two issues of this story, The Envelope Manufacturer. The realities of running a publishing company on a shoestring prevented him from finishing that story until he started it again from scratch in 2011. Turning the day-to-day operations of the company over to his trusted lieutenants (and new co-publishers) Tom Devlin and Peggy Burns meant that he had time to finish the book, which he is self-publishing but is having distributed by D&Q. Reading the book made me realize how much I had missed his cartooning, which has elements of Seth and Chester Brown in the sense that they had a number of common influences. Oliveros line is gloriously scratchy and cartoony at the same time, with the book's themes of obsolescence and loss resonating with the profoundly old-fashioned character design. The patchy hair of the company's owner, the suit-bursting girth of his main employee and the bespectacled dowdiness of his other employee are all striking, iconic images that feel strange and almost out of place in a modern book.

That sense of alienating the reader with the evocation of a past time and place is one of the central points of the book, which on the surface resembles Seth's Clyde Fans in that it depicts a failing company that fell prey to obsolescence and its now-useless employees. Where it differs is that Seth's story is at once fixated on surface details but also a deeply interior story that follows the twisting memories of two bitter brothers. The Envelope Manufacturer, on the other hand, has a sense of humor that's both absurd and black as pitch, creating what amounts to scene after scene of dark slapstick. The book's plot, such as it is, involves the last days of a tiny office supply producer. When a key machine breaks down, it signals the end of the company, even as the owner is in complete denial regarding this and has been for some time.

The owner, Mr. Cluthers, is constantly muttering to himself about ways to save the company. His employee, Hershel, is sunk because he's owed a lot of back pay, but it emboldens him to mouth off constantly. So much so that Cluthers thinks he sees Hershel bloviating on a bus and hallucinates choking him. Hershel takes to yelling at failing businessmen to jump from their tall buildings. There's a hilarious sequence where a business owner who's in the process of jumping off the building comes into Cluthers' office, uses his bathroom, offers him some advice and then jumps. When all of the broken-down equipment is repossessed, Cluthers is still obsessed with the idea of making the envelopes by hand, as just one order can help them get out of the red.

The book works as a metaphor for any kind of personal endeavor that's endangered by the whims of the market, and it's not too much of a leap to transfer the sheer absurdity of a three-person envelope manufacturing concern to an equally small art-comics publishing company. Yet one can see Oliveros in D&Q's darkest days, betting on the next book to keep the company going. That said, what marks the characters in this book are their unrelentingly obsessive personalities, an obsession that borders on narcissism and self-delusion. The tiny, scratchy lines on the page give them a nervous, twitchy energy that is especially effective juxtaposed against the classic character and building design. Oliveros proves to be highly proficient in both character and caricature, and the blending of those two worlds gives the book an uneasy sense of both charm and desperation.

No comments:

Post a Comment