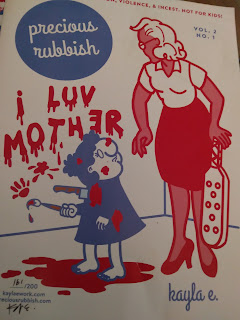

Kayla E. is one of the most exciting young talents in the world of alternative and literary comics in quite some time. I've been following her progress in minis and in places like Nat. Brut, but she's gone to another level recently. She's working on a memoir for Fantagraphics, and hints of what will wind up in that book can be found in two recent minicomics: Fun Time Fun Book and Precious Rubbish Vol. 2 No. 1. Kayla E. writes about her horrifying childhood and the unthinkable abuse she suffered, but it's mediated through Ivan Brunetti-style simplicity and filtering her experiences through old Archie and ACG comics.

In much the same way that her comics collection was her safe haven as a child, so too does the style of people like Harry Lucey and Bob Wickersham inform and guide her through a harrowing juxtaposition of kid comic wholesomeness with mental illness, abuse, family dysfunction, violence, incest, and withholding of emotion. In Fun Time Fun Book, Kayla. E gives the reader word searches, paper dolls, fashion, and crossword puzzles. However, they are all about horrible things, like her mother's borderline personality disorder, Kayla E.'s desperate attempts to please her, and details like her older brother having a peephole into her room. There are also references to her drinking issues and desperate need to imprint on others for love and approval.

Precious Rubbish is a series of short stories done in the model of ACG stories, MLJ stories, and Archie. Most of them are about her mother and the bizarre behavior she engaged in. Her parents divorced and Kayla mostly lived with her mom, who had little interest in actual parenting. Throughout her stories, religious iconography is crucial, as her own unique interpretation and relationship with Christianity informs her comics now, just as it did her beliefs as a child. There's a heartbreaking sequence where she fantasizes that Jesus is her mother, and she becomes Christ-like, only to have an overwhelming desire to have her insides scraped out so that she becomes someone else. In the Archie-style story involving baking, the dialogue all comes from the book of Job while the captions are all memories of abuse, but also bizarre events like watching her mother go through an exorcism. No fantasy and no nightmare could keep up with actual events that were occurring, and this is a reality barely kept at bay in her comics with her grotesque self-caricature facing a series of impossible trials with little to no reward or any sense of a way out. Yet, the art itself is a reaction, a howl against her experiences, and a statement of purpose.