The following article was originally published at sequart.com in 2007. Austin is now the publisher of Domino Books. Please consider buying one of the many excellent works he's released, especially since he's losing his base of operations (the legendary Cartoon House). Get the first five Domino books for just 26 bucks, with free shipping. All of them are quite good and unlike most comics you've ever seen.

*************************

My favorite kinds of publications about comics, as I have noted in this series, are those that reflect the idiosyncrasies and passions of its editors. Windy Corner Magazine (WCM) is an exemplar of such a publication. I am particularly drawn to WCM because I share some of editor Austin English's more eccentric tastes, and he does little to buffer or prepare the average reader for them. It's a tact that can be a little demanding on a reader not familiar with English's approach to comics and criticism. The focus of WCM is artists writing about and talking to other artists, an approach that makes sense given English's status as an artist and critic.

I like the give-and-take collaborative feel of WCM. Lis Timpone designed a clever table of contents. Molly Goldstrom opened up the magazine with an odd two-page strip where a man prattling on about his love of bricks fails to notice his companion turn into a tree. Juliacks contributed the back cover, a typically dense collage of image, tone and text with a certain wistful quality.

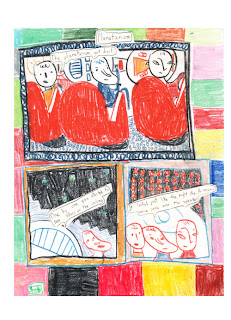

English continues his autobiographical series of comics with a couple of evocative entries. The emphasis of these stories is on his earliest childhood memories, and I love the way he homes in on tactile sensations from memory, like the feel of the chair he sat in, the distress he felt upon hearing the sound and flash of a star "explode", and the soothing sound of the planetarium show's narrator. In "Movie", his memory is as much about the way he interacted with his parents before and after a movie he saw as the movie itself. The former story looks like it was done in colored pencil, and the decorative quality of the colors he uses to balance out his panels is striking. It balances the panels and actually draws the eye in, something lacking in the second story. That sort of pleasantly ramshackle design quality of his works nicely in his second "Life of Francis" episode, which is almost expressionistic in the way it depicts feeling and emotion. Fiona Logusch's "Entangled Relationships" reminds me a bit of Jules Feiffer's work, both in terms of the way she moves her characters around and the rawness of the emotions she portrays.

The feature article on children's book illustrator Lois Lenski was positively inspiring. English is unusual for a critic in that he seems to have an intuitive sense in how to discuss the formal qualities of a work in such a way as to bring it alive for the reader. I knew nothing about Lenski's work going into this article, and English probably would have been well-served to have at least some sort of introduction to her work. That said, I appreciate his enthusiasm about the subject and the way he quickly immerses the reader in the formal and aesthetic qualities of Lenski's art.

The interview in this issue was one of the most enlightening I've ever read with a cartoonist. John Hankiewicz, creator of enigmatic & beautiful comics in minicomics and the collection Asthma, was interviewed by cartoonist Onsmith. Hankiewicz reveals much about his working process, the way he approaches doing comics, why he loves printmaking, the specifics of certain stories and his general aesthetic outlook. Onsmith uses his deep knowledge and appreciation of Hankiewicz's work to take the conversation to some interesting places, but he always allows Hankiewicz room to expand on his thoughts.

The standout feature in an issue filled with great features is Dylan Williams's strip about Alex Toth. It's a series of stand-alone images done in what looks like colored chalk, each accompanied by a caption loosely associated with (almost interpreting) the text. It's a wistful piece dedicated to Toth and the intermittent correspondence that Williams had with him over the years. It's also about relationships and friendships and the way Williams approached them and how his feelings about them changed. It ends with a statement of purpose that connects his feelings about being an artist, about Toth, about comics and about long-distance friendships. I can only imagine this piece running in a magazine like Windy Corner , and that's why Austin English's indulgence in his aesthetic passions winds up as a gift to readers.

*************************

My favorite kinds of publications about comics, as I have noted in this series, are those that reflect the idiosyncrasies and passions of its editors. Windy Corner Magazine (WCM) is an exemplar of such a publication. I am particularly drawn to WCM because I share some of editor Austin English's more eccentric tastes, and he does little to buffer or prepare the average reader for them. It's a tact that can be a little demanding on a reader not familiar with English's approach to comics and criticism. The focus of WCM is artists writing about and talking to other artists, an approach that makes sense given English's status as an artist and critic.

I like the give-and-take collaborative feel of WCM. Lis Timpone designed a clever table of contents. Molly Goldstrom opened up the magazine with an odd two-page strip where a man prattling on about his love of bricks fails to notice his companion turn into a tree. Juliacks contributed the back cover, a typically dense collage of image, tone and text with a certain wistful quality.

English continues his autobiographical series of comics with a couple of evocative entries. The emphasis of these stories is on his earliest childhood memories, and I love the way he homes in on tactile sensations from memory, like the feel of the chair he sat in, the distress he felt upon hearing the sound and flash of a star "explode", and the soothing sound of the planetarium show's narrator. In "Movie", his memory is as much about the way he interacted with his parents before and after a movie he saw as the movie itself. The former story looks like it was done in colored pencil, and the decorative quality of the colors he uses to balance out his panels is striking. It balances the panels and actually draws the eye in, something lacking in the second story. That sort of pleasantly ramshackle design quality of his works nicely in his second "Life of Francis" episode, which is almost expressionistic in the way it depicts feeling and emotion. Fiona Logusch's "Entangled Relationships" reminds me a bit of Jules Feiffer's work, both in terms of the way she moves her characters around and the rawness of the emotions she portrays.

The feature article on children's book illustrator Lois Lenski was positively inspiring. English is unusual for a critic in that he seems to have an intuitive sense in how to discuss the formal qualities of a work in such a way as to bring it alive for the reader. I knew nothing about Lenski's work going into this article, and English probably would have been well-served to have at least some sort of introduction to her work. That said, I appreciate his enthusiasm about the subject and the way he quickly immerses the reader in the formal and aesthetic qualities of Lenski's art.

The interview in this issue was one of the most enlightening I've ever read with a cartoonist. John Hankiewicz, creator of enigmatic & beautiful comics in minicomics and the collection Asthma, was interviewed by cartoonist Onsmith. Hankiewicz reveals much about his working process, the way he approaches doing comics, why he loves printmaking, the specifics of certain stories and his general aesthetic outlook. Onsmith uses his deep knowledge and appreciation of Hankiewicz's work to take the conversation to some interesting places, but he always allows Hankiewicz room to expand on his thoughts.

The standout feature in an issue filled with great features is Dylan Williams's strip about Alex Toth. It's a series of stand-alone images done in what looks like colored chalk, each accompanied by a caption loosely associated with (almost interpreting) the text. It's a wistful piece dedicated to Toth and the intermittent correspondence that Williams had with him over the years. It's also about relationships and friendships and the way Williams approached them and how his feelings about them changed. It ends with a statement of purpose that connects his feelings about being an artist, about Toth, about comics and about long-distance friendships. I can only imagine this piece running in a magazine like Windy Corner , and that's why Austin English's indulgence in his aesthetic passions winds up as a gift to readers.