Friday, June 29, 2012

Talking Tatsumi: Fallen Words

At the age of 77, it's remarkable to see just how restless Yoshihiro Tatsumi is as an artist. The father of gekiga ("dramatic pictures"), a subset of manga notable for its realism and mature subject matter, can't seem to help wanting to continue to innovate, even in the twilight of his career. There's no question that the quality of his cartooning is still masterful, with a loose but fluid line at work in depicting the characters in this series of period-piece short stories. Indeed, his book of all-new material, Fallen Words, acts as a work of comics fusion, with some very interesting source material. He combines the dark tones and harsh emotional truths of gekiga with the oral storytelling tradition known as rakugo ("fallen words"). In many respects, this innovative fusion actually goes back to his roots and the roots of modern manga itself.

Tatsumi started drawing manga as a teenager by submitting 4-panel comedy pieces to publications that catered to children and sought their material. Before manga was widely available, there were also men who used to go around in public and charge a small fee to read and re-enact popular stories of the day. Though Tatsumi quickly grew bored with doing gag strips, and those performers disappeared after the paper shortage ended, it's clear that some part of that development remained a part of his creative DNA. It's no wonder he was drawn to rakugo, a comedic and performative oral storytelling tradition that goes back many centuries and is still alive today. His task was turning these fables into visual narratives on the page, bringing out the pathos as much as he guided each story to its gag or twist ending. His light, cartoony style makes it easy to retain the humor in each piece, but his deliberate pacing adds an air of solemnity to even the most ridiculous story. That actually makes it funny, as Tatsumi the artist becomes the perfect straight man for Tatsumi the jokester.

Take "Escape of the Sparrows", which may well be the world's oldest shaggy dog story. It's a fascinating, elaborate and even elegant story about an artist with no money who manages to con himself into a stay at an inn, complete with being severed sake morning, noon and night. Tatsumi begins this story talking about a particular piece of Japanese history regarding travel: it was done either by horse or by palanquin, a sort of carriage carried by two men. Known as "the cage", the highly disreputable rough-and-tumble types who carried them were known as "cage drawers". That detail is set aside as the artist paints the innkeeper some sparrows as collateral until he returns with money. Miraculously, the sparrows fly off of the canvas every morning and eat, returning to the stillness of the painting afterwards. Tatsumi builds tension by piling on detail after detail of how the innkeeper started to grow rich thanks to the customers who wanted to witness this miracle. An older man comes by, guesses who painted the sparrows, and then notes that they are dying. He offers to paint a branch for them to sit on so they can rest, and draws a cage around that. When the young artist returns weeks later, he is despondent. The reason he gives is the shaggy dog joke's punning punchline, a head-slapping groaner that took me completely by surprise. Like all great shaggy dog stories, it's the details between premise and punchline that make it stand out.

The other stories range between the mundane and the totally ridiculous. A spooky story featuring the spirits of a man's wife and mistress battling each other beyond the grave has another shaggy-dog joke ending, but that doesn't detract from the can-you-top-this viciousness of their jealousy. A story about a brat getting a small bit of comeuppance is entertaining not so much for the punchline (which is weak sauce) but for the way Tatsumi brings the brat to life with astonishing force. He really is the worst kid in the world, matched only by his indifferent father. "The God of Death" is a genuinely creepy story with yet another gag as a punchline--only this time the gag has fatal consequences. Not every story resonates with a non-Japanese audience; the ending of "The Innkeeper's Fortune" fell flat because the punchline (having to do with wearing sandals indoors) is something that would be obvious to a Japanese person but a bit out of the purview of Western audiences. Leading off the collection with this story (and the equally weak gag of "New Year Festival", the story about the brat) was confusing to me as a reader, because I had no idea what on earth Tatsumi was trying to do. Reading some of the background information about the history of rakugo helped, but things also became much clearer by the time I got to "Escape of the Sparrows".

There's an earthiness to these stories that made them feel quite modern. Considering that most of the characters in the book were either trying to get drunk or trying to get laid at a brothel (the source of many jokes), Tatsumi cleverly bridges the divide between cultural politeness and the realities of everyday living. The final story in the book, "Shibahama", is a bit more along the lines of an O. Henry story in its mild twist ending that sentimentally confirms that a wife's decision to fool her husband into thinking that his discovery of a walet stuffed with money was just a drunken dream was the right one. Tatsumi takes the lessons and jokes dealt at the end of each of these stories and reverse-engineers the stories into one that matches the tone and earthiness of his own stories. Oral traditions depend on the cleverness of each generation to subtly adapt and evolve their stories while retaining their essence, and Tatsumi's attention to background detail and period eccentricities is a big part of the creating the atmosphere in these stories that allows the joke to develop naturally. It also doesn't hurt that a performative art like rakugo is an inherently visual medium, making it a little easier for Tatsumi to frame his comics. Still, it's Tatsumi alone whose character design is so essential in getting across so much of the humor, allowing even a Western audience to understand most of what he was attempting without too much difficulty. More to the point, this book sees the short story master creating a coherent work that is nonetheless comprised of the short stories for which he is known. While none of the stories are directly linked to each other, they still take place in the same time, the same place and with the same sense of humor, a pitch-black kind of comedy that incorporates the lowest forms of humor with a frequently nasty view of humanity. Tatsumi's work manages to be simultaneously dark and uplifting, allowing the reader to identify with and laugh at foibles we all share.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Talking Tatsumi: Black Blizzard

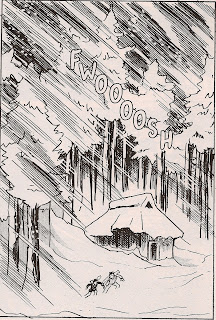

In 1956, at the tender age of 21, Yoshihiro Tatsumi was already a three-year manga veteran, having drawn 17 volumes and numerous short stories. As depicted in his memoir A Drifting Life, he was inspired by the novel The Count of Monte Cristo to create a prison escape yarn. Always driven to innovate and experiment, the young man blasted out the prison escape thriller Black Blizzard in a mere twenty days, a spate of creativity that saw him write and draw six pages a day! It was unlike anything that had been produced by a Japanese artist, though its hard-boiled story will seem familiar to modern audiences. The book really does look like it poured out of Tatsumi's pen, even as he came up with interesting formal tricks on the fly. For example, as Tatsumi's brother points out, a large portion of the story is dominated by diagonal lines, so as to represent the titular blinding snowstorm. It's all part of what Tatsumi does best in this story: create atmosphere.

The story involves a hard-boiled cardshark and a pianist framed for murder traveling under police supervision on a train. When the train derails, the pair, handcuffed together, flees the scene. Tatsumi creates a tense atmosphere for the duo, with howling winds, unrelenting police searches and their own distrust of each other. The card shark eventually declares that they'll never get anywhere bound together and pressures the pianist to chop off his hand. When he naturally refuses, this becomes a running conflict that is set on hold temporarily when they try to escape their pursuers but later picked up again in earnest. If Tatsumi makes a mistake as a storyteller here, it's the way he has the pianist artlessly talk about his backstory, wherein he fell in love with a circus singer and was subsequently given the brush off by the man who claimed to be her father--the ringmaster. While Tatsumi makes it pretty obvious who the real killer is, he throws another curveball at readers that's quite clever, redeeming the long flashback in the middle of the otherwise tense narrative. The concluding scenes are genuinely gripping, with all sorts of interesting twists and turns.

Tatsumi's formal tricks are interesting, even if they all seem familiar today. Still, they fit seamlessly in with the narrative, with every technique serving the story and the atmosphere he creates. At this point of his career, his grasp of anatomy was rudimentary at best, giving a number of pages a cartoony quality that he was unlikely trying to convey. As a result, his figure drawing is a bit on the melodramatic side as he really tries to sell the book's uneasy showdown scenes. At the same time, his understanding of body language and how figures relate to each other was already quite strong, giving these scenes their true power. The overall result is something every bit as good as a contemporary EC comics potboiler (in terms of the writing and formal innovations), which is pretty astounding when one considers Tatsumi's age and the fact that he was making it up as he went along. Tatsumi described the feeling of doing this book as the cartoonist's equivalent of the "runner's high"; at a certain point, things like fatigue fell away for a sensation of pure joy in the sheer act of putting pen to paper. While lacking the thematic sophistication of his later comics, Black Blizzard is a fine genre comic that delivers thrills and pathos in equal measure.

The story involves a hard-boiled cardshark and a pianist framed for murder traveling under police supervision on a train. When the train derails, the pair, handcuffed together, flees the scene. Tatsumi creates a tense atmosphere for the duo, with howling winds, unrelenting police searches and their own distrust of each other. The card shark eventually declares that they'll never get anywhere bound together and pressures the pianist to chop off his hand. When he naturally refuses, this becomes a running conflict that is set on hold temporarily when they try to escape their pursuers but later picked up again in earnest. If Tatsumi makes a mistake as a storyteller here, it's the way he has the pianist artlessly talk about his backstory, wherein he fell in love with a circus singer and was subsequently given the brush off by the man who claimed to be her father--the ringmaster. While Tatsumi makes it pretty obvious who the real killer is, he throws another curveball at readers that's quite clever, redeeming the long flashback in the middle of the otherwise tense narrative. The concluding scenes are genuinely gripping, with all sorts of interesting twists and turns.

Tatsumi's formal tricks are interesting, even if they all seem familiar today. Still, they fit seamlessly in with the narrative, with every technique serving the story and the atmosphere he creates. At this point of his career, his grasp of anatomy was rudimentary at best, giving a number of pages a cartoony quality that he was unlikely trying to convey. As a result, his figure drawing is a bit on the melodramatic side as he really tries to sell the book's uneasy showdown scenes. At the same time, his understanding of body language and how figures relate to each other was already quite strong, giving these scenes their true power. The overall result is something every bit as good as a contemporary EC comics potboiler (in terms of the writing and formal innovations), which is pretty astounding when one considers Tatsumi's age and the fact that he was making it up as he went along. Tatsumi described the feeling of doing this book as the cartoonist's equivalent of the "runner's high"; at a certain point, things like fatigue fell away for a sensation of pure joy in the sheer act of putting pen to paper. While lacking the thematic sophistication of his later comics, Black Blizzard is a fine genre comic that delivers thrills and pathos in equal measure.

Monday, June 25, 2012

Talking Tatsumi: A Drifting Life

Despite my interest in international comics, one of my long-time blind spots has been manga. This is for any number of reasons: the clannishness of its American fans that makes entry into manga seem impenetrable at times; the sheer amount of material; but most especially the juvenile nature of much of its subject matter. Of course, there is also a long history of adult, experimental manga, and a smattering of that is being translated for American audiences. What better place to start than with the work of Yoshihiro Tatsumi, one of the creators of gekiga. That word refers to comics that broke that standard rules of manga and eventually dealt with the kind of ideas and topic of everyday life that alt and underground comics would later address in the US and Europe. I'll be examining three of Tatsumi's translated comics this week: A Drifting Life, Black Blizzard and his new collection of comics, Fallen Words.

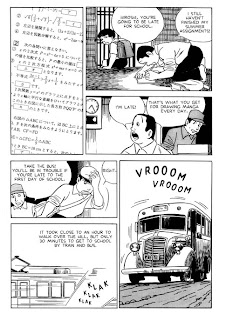

A Drifting Life is a slightly autobiography, detailing Tatsumi's entry into doing manga as an amateur and ending with his continuing allegiance to the style he pioneered. For a book that's 800+ pages, it's quite a breezy read, with Tatsumi breaking up his personal narrative with chapter breaks, complete with splash-page illustrations for each new chapter. He also makes a point of ending each chapter either with a cliffhanger, a concluding panel or an allusion to how current events might affect the future. For Tatsumi, who started getting his work published as a teenager (along with his brother), the personal and professional are entirely intertwined. Telling the story of how he became an artist meant not only talking about his family and personal life, it meant talking about the cultural and political history of Japan in the postwar era and the 1950s. It's a story that begins with deprivation and a family beset by sickness and an undependable father, with any number of ups and downs as Japan slowly rebuilt itself into an international economic power. During a time when there weren't necessarily a lot of great jobs available, it was perhaps less of a big deal for young "Hiroshi Katsumi" (Tatsumi's name altered for the book) to be a manga fanatic.

There's a delightful purity in Tatsumi's obsession with reading and drawing manga, especially when he's able to meet with the great Osamu Tezuka (the most influential manga artist of all time and a standard top-five pick for greatest cartoonist ever) and gain confidence. Throughout the book, Tatsumi is a man in the right place at the right time, even if it leads to the directionless "drifting life" of the title, where one is at the whim of one's publishers. As a result, he's able to publish an astounding number of books (mostly aimed at children) in a ridiculously short period of time, even as he becomes dissatisfied with what he's doing and longs to do full-length, intelligent comics--at the very least, comics for teenagers and not pre-teens.

This book is masterful because Tatsumi is able to create a remarkable storytelling rhythm while keeping a number of scenarios in his rotation. The book is partly about his family, with his occasionally shiftless father and his older brother being the key characters. His brother, who is sick for the early part of the book, is also a manga fanatic and is jealous that his brother is making money from publishing manga and hanging out with Tezuka while he has to go to the hospital. Later, his brother joins him as an author and co-initiator of the gekiga movement. The book is also about the bizarre and colorful characters in the world of Japanese manga publishing, with the Hinomaru group being the craziest. Publishers trying to get sole custody of artists, wars between publishers, representatives tracking down artists in person and other histrionics are played both seriously and for laughs by Tatsumi. He plays up the ridiculousness of the situation in the goofy way he draws a number of these characters, giving their eyes a crazy glint. Kurodo, the hard-drinking, bitter "sensei" of Hinomaru, is an amusing figure with his beret and unshaven face. The book is also about Tatsumi's quest to develop himself as an artist, his struggles with productivity at times, his creative breakthroughs and the ways in which the money flying around for manga had an enormous impact on him and his friends. In this way, the book reminds me a bit of the three-volume The Dick Ayers Story, by the American artist whose tenure extends back to the Golden Age. He spends a lot of the book discussing his assignments, how much he makes for each one, and how that adds up at the end of each year. The book is also about the artistic community and the friendly nature of their competition as the young guns tried to one-up each other with new and more creative new techniques in making comics. Finally, the book is also about Tatsumi as a young man trying to figure out how to deal with women and how to best incorporate other cultural influences, even as Japan slowly starts to revive as a country and a culture.

Tatsumi's portrayal of himself is fascinating. He draws himself wide-eyed and goofy as if to emphasize his naivete', with a cartoony block head and slightly bulbous nose. He's hopelessly earnest about his art and hopelessly clueless about business, until he starts to grow up a bit and puts his artistic interests ahead of everything else. He also doesn't spare himself for criticism when he goes to Tokyo and starts to act irresponsibly. It's a bit distracting at times to read about this goofy-looking character who takes himself and his ideas so seriously, but Tatsumi makes it work with his overall light touch and stunning talent for caricature. His understanding of body language, gesture, and the ways in which bodies relate to each other in space is surpassed only by Jaime Hernandez, and this is why A Drifting Life is such a compelling read, despite the occasional dryness of its subject matter. Tatsumi uses his instincts as a former detective story writer to keep the reader in suspense, plays up the crazy nature of publishing in the 1950s, and when in doubt, uses himself as comic relief. The result is a memoir that's less about the author than it is about the author's ideas and a particular era. For this reader, it served as both as a powerful narrative and a much-appreciated introduction to an underdiscussed aspect of manga history.

A Drifting Life is a slightly autobiography, detailing Tatsumi's entry into doing manga as an amateur and ending with his continuing allegiance to the style he pioneered. For a book that's 800+ pages, it's quite a breezy read, with Tatsumi breaking up his personal narrative with chapter breaks, complete with splash-page illustrations for each new chapter. He also makes a point of ending each chapter either with a cliffhanger, a concluding panel or an allusion to how current events might affect the future. For Tatsumi, who started getting his work published as a teenager (along with his brother), the personal and professional are entirely intertwined. Telling the story of how he became an artist meant not only talking about his family and personal life, it meant talking about the cultural and political history of Japan in the postwar era and the 1950s. It's a story that begins with deprivation and a family beset by sickness and an undependable father, with any number of ups and downs as Japan slowly rebuilt itself into an international economic power. During a time when there weren't necessarily a lot of great jobs available, it was perhaps less of a big deal for young "Hiroshi Katsumi" (Tatsumi's name altered for the book) to be a manga fanatic.

There's a delightful purity in Tatsumi's obsession with reading and drawing manga, especially when he's able to meet with the great Osamu Tezuka (the most influential manga artist of all time and a standard top-five pick for greatest cartoonist ever) and gain confidence. Throughout the book, Tatsumi is a man in the right place at the right time, even if it leads to the directionless "drifting life" of the title, where one is at the whim of one's publishers. As a result, he's able to publish an astounding number of books (mostly aimed at children) in a ridiculously short period of time, even as he becomes dissatisfied with what he's doing and longs to do full-length, intelligent comics--at the very least, comics for teenagers and not pre-teens.

This book is masterful because Tatsumi is able to create a remarkable storytelling rhythm while keeping a number of scenarios in his rotation. The book is partly about his family, with his occasionally shiftless father and his older brother being the key characters. His brother, who is sick for the early part of the book, is also a manga fanatic and is jealous that his brother is making money from publishing manga and hanging out with Tezuka while he has to go to the hospital. Later, his brother joins him as an author and co-initiator of the gekiga movement. The book is also about the bizarre and colorful characters in the world of Japanese manga publishing, with the Hinomaru group being the craziest. Publishers trying to get sole custody of artists, wars between publishers, representatives tracking down artists in person and other histrionics are played both seriously and for laughs by Tatsumi. He plays up the ridiculousness of the situation in the goofy way he draws a number of these characters, giving their eyes a crazy glint. Kurodo, the hard-drinking, bitter "sensei" of Hinomaru, is an amusing figure with his beret and unshaven face. The book is also about Tatsumi's quest to develop himself as an artist, his struggles with productivity at times, his creative breakthroughs and the ways in which the money flying around for manga had an enormous impact on him and his friends. In this way, the book reminds me a bit of the three-volume The Dick Ayers Story, by the American artist whose tenure extends back to the Golden Age. He spends a lot of the book discussing his assignments, how much he makes for each one, and how that adds up at the end of each year. The book is also about the artistic community and the friendly nature of their competition as the young guns tried to one-up each other with new and more creative new techniques in making comics. Finally, the book is also about Tatsumi as a young man trying to figure out how to deal with women and how to best incorporate other cultural influences, even as Japan slowly starts to revive as a country and a culture.

Tatsumi's portrayal of himself is fascinating. He draws himself wide-eyed and goofy as if to emphasize his naivete', with a cartoony block head and slightly bulbous nose. He's hopelessly earnest about his art and hopelessly clueless about business, until he starts to grow up a bit and puts his artistic interests ahead of everything else. He also doesn't spare himself for criticism when he goes to Tokyo and starts to act irresponsibly. It's a bit distracting at times to read about this goofy-looking character who takes himself and his ideas so seriously, but Tatsumi makes it work with his overall light touch and stunning talent for caricature. His understanding of body language, gesture, and the ways in which bodies relate to each other in space is surpassed only by Jaime Hernandez, and this is why A Drifting Life is such a compelling read, despite the occasional dryness of its subject matter. Tatsumi uses his instincts as a former detective story writer to keep the reader in suspense, plays up the crazy nature of publishing in the 1950s, and when in doubt, uses himself as comic relief. The result is a memoir that's less about the author than it is about the author's ideas and a particular era. For this reader, it served as both as a powerful narrative and a much-appreciated introduction to an underdiscussed aspect of manga history.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Help Fund Steve Lafler's Tour

Steve Lafler is going on tour to promote Menage a Bughouse, his new collection of the three superb Bughouse books originally published by Top Shelf. In the interest of full disclosure, I will be appearing at one of his stops to do a panel with Steve and Austin English, at MOCCA in New York on July 12th. Since he's using Indiegogo, he will receive all funds donated. Take a look at his website, and please donate if you are so inclined.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Answering The Two Questions: Everything, Vol 1: Blabber Blabber Blabber

It's heart-breaking to think how close Lynda Barry's works came to falling into complete obscurity. A mainstay of the dwindling alt-weekly newspaper market, her collections were all out of print and no publishers were interested in her books. To the rescue came Drawn & Quarterly, publishing two original books based on her creativity course, the excellent and inspiring What It Is and Picture This. D&Q's next project was reprinting her complete works, in a series of volumes aptly titled Everything. The first volume, subtitled Blabber Blabber Blabber, is a new kind of comics reprint. It's a reprint that features new annotations by Barry done in her unique mix of handwriting, collage, painting and comics, the style she used for her past two books. It's an approach that makes the book look constructed as much as it's drawn, and puts her comics into historical and personal contexts. Given that What It Is was as much autobiography as it was instructional book, it's obvious that the simple act of drawing is the single most important factor in understanding Barry and how she reacted to a clearly fractious childhood.

Barry sadly notes that there aren't many of her actual childhood drawings that are extant, so the bulk of the strips here are from ages 25-28. The comics in this volume can be divided into roughly three sections that are all quite different. The first features the early years of "Ernie Pook's Comeek" and mostly tend to be sweet, silly and absurd comics. The second section features "Two Sisters", a strip that merged that early surrealism with a painful verisimilitude that felt too personal too be fictional. The third section features "Boys and Girls", a collection of strips about relationships that tipped heavily on the bitter side of storytelling. Barry talks about trying to balance bitter and sweet in her storytelling, changing her strip depending on which style she felt more affinity with. She also notes that the two ingredients require a third, ineffable quality that is difficult to talk about but obvious when present.

Very early in her career, Barry's style had the "beautifully ugly" quality that she continues to employ in her modern comics. One can see the hand of her friend Gary Panter at work in a lot of her early work, but it's clear that the cynicism of her former college editor Matt Groening inspired her to explore the darkest areas of her mind. Even the darkest of her strips still has a strange buoyancy, in part because drawing itself is a buoyant activity for Barry. When exploring the ways in which a parent can be uniquely hurtful to her children, or the ways in which men and women mistreat each other or refuse to understand each other, there's a cheeriness in the quality of her drawings that makes these strips inspiring to read. It's a quality she shares with Mark Beyer, whose suicidal Amy and Jordan strips were hilarious precisely because of the quality of his line. The raw nature of Barry's stylization brings out what's funny about the darkest of situations, letting us laugh even when her characters are despondent.

The depth and richness of characterization Barry would achieve later in her career with her weekly strip is not present in this first volume of strips, as she mostly flits from situation to situation and character to character. The exception is in the strange conclusion of Two Sisters, where the unseen mother of the quirky girls is suddenly thrust front and center as she goes back in time to her teenage years, only she has her current memories. It's strange and touching to see her struggle with her life and her sister after seeing the way she struggled as a mother. Barry understandably lost steam with that strip, clearly wanting to explore not only a new tone of storytelling, but she laid the foundation for the kind of comics for which she would become best known. That's probably the best way to look at this book, as the seeds for greater work to come, but there's plenty to like here on its own merits. Anyone seriously interested in her work needs to read this book, especially for her annotations. It's gratifying that this, the Golden Age of Reprints, is not neglecting great and uncollected work from the 1980s, and the fact that Barry is being unambiguously being regarded as one of the great cartoonists is a direct result of the care that D&Q has shown in keeping her work alive.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

The Color of Night: The Wrong Place

Brecht Even's The Wrong Place is a simple triptych of stories about the nocturnal social adventures of two longtime friends.It's a visually stunning achievement in the way Evens uses watercolors to create his comics page, giving it a surprising amount of structure and solidity. What I like best about it is Evens' lack of judgment regarding his two protagonists, Gary and Robbie. Gary is a classic comics sad-sack loser who is desperate to be liked and loved, while Robbie leads a charmed life, creating entire social scenes simply by showing up. Robbie has a fantastic sort of naivete', flitting from person to person without entirely understanding the effect he has on them. Gary is oblivious in a different way, not entirely wanting to understand why people have no desire to be around him. They're both social mirrors: Robbie reflecting confidence, joy and spontaneity and Gary reflecting self-loathing and desperation. To be around them is to see either the best or worst in oneself, though neither seems to fully understand this as both are narcissistic in different ways.

The book's first segment sees Gary throwing a party, luring a bunch of people up to his lame event in a fifth-floor walk-up apartment. The reader slowly learns that every guest came because they though Robbie, Gary's childhood friend, would be there. In a series of hilariously awkward interactions, Gary completely fails to successfully engage any of his guests (my favorite part is when he tells one of his guests to crank up Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze" as party music), keeping them at his part only because Robbie has assured him he would show up later. When he finally doesn't show, everyone leaves. The second segment begins with a shy young woman who is hung up on Robbie going through the process of getting ready to go out to a club he likes, in hopes of seeing him. She hits the jackpot, hooking up with Robbie and getting caught up in his magical trail. Robbie is one of those rare individuals who has the power to create a magical adventure no matter where he goes, and if you're lucky enough to be picked to go with him, you get to be part of that story. The price one pays, as she learns, is that once the night is over, so is the magic. Robbie's ability to totally engage with someone and then detach completely is what makes everyone fall in love with him and follow him around, hoping that he might come around to them again.

That's what makes the third segment so interesting. Gary goes to Robbie's favorite club, and his old friend greets him warmly. While Robbie is happy to reminisce about old times, it's clear that Gary wants to bask in the glow of his friend's charisma and go on a magical adventure. Gary clearly wishes that he could have Robbie to himself all the time, though the attraction isn't a sexual one; Robbie's charisma makes straight men want to be his partner in adventure. Robbie takes him on one of these adventures, but when the time comes for Gary to jump off a balcony to get caught by a crowd like Robbie just did, he demurs. Robbie assures his friend that the crowd will catch him, but Gary doesn't do it. Part of the reason he draws back, I would guess, is that he's simply afraid to take a risk; he has no confidence in himself. There are other reasons, though: he may well think that the crowd won't catch him, because he's Gary and Robbie is Robbie. More to the point, he can pretend to be like Robbie, but in the end he can't do the things that Robbie does, and that scene is cold, hard proof. That scene is the dawning realization that he's kidding himself to think otherwise. Though Robbie urges him to push on through, he eventually lets his friend go, accepting him as he accepts everyone.

This book is one of the splashiest characters studies I've ever read, as Brecht uses the looseness of his watercolor approach to get expressionist and almost abstract on some pages, like the sex scene with Robbie and the girl he picks up in the second part of the book. The reader is fully pulled into the strange night world of the club, with patches of darkness being illuminated by gaudy outfits and colorful lights. The sections of the book that are devoted to characters thinking and talking about Robbie are as interesting as the Robbie segments themselves, and Evens doesn't disappoint by talking up Robbie for a chapter and a half before finally introducing him to the reader. Robbie is a tall, odd-looking person who has a simple and powerful sense of enthusiasm that others emulate because of the way he embraces life and the ease in which he negotiates every environment. One gets the sense that if he had asked to hear Jimi Hendrix at Gary's party, others would have gone along with it gladly. Evens impressively conjures up a setting where the stakes are high for its participants, even if they seem low to an outside observer. It's a period of time as a young person where one's nocturnal adventures are both a tether to youth and what gives meaning in an otherwise dull life, and Evens captures every detail along the way, both for his male and female characters.

Monday, June 18, 2012

No Romance: Paying For It

Chester Brown's highly-publicized Paying For It drew a lot of controversy for his views on the legalization of prostitution. To be sure, he spends much of this book discussing his experiences as a john and discusses the pros and cons. He backs all of this up with a detailed set of appendices arguing his points further, making the book less a memoir than an out-and-out polemic. I would argue, however, that the view he's arguing most vehemently is not in favor of prostitution, but against romantic love. To be sure, he has to move the goalposts several times in order to precisely define what he's opposed to with regard to romantic love, eventually settling on "possessive monogamy" as the villain of his book. I don't use the word lightly, given that he out-and-out declares marriage and romantic love to be "evil", an assertion that he argues almost entirely by anecdote rather than reason or statistics. As a philosophical argument, arguing by anecdote tries to make universal one particular personal observation. However, asserting that fire is bad because one person you know got badly burned is an erroneous leap of logic. By the same token, Brown's own miserable experiences in romantic relationships naturally prejudice him against the very concept of "possessive monogamy".

It's difficult to review this book without coming to grips with the arguments he puts forth. As such, in most respects I find it to be Brown's least significant work in a body of work that is obviously extremely accomplished and significant. One can't overestimate the impact a story like Ed The Happy Clown and I Never Liked You on a couple of generations of cartoonists, and Louis Riel was also a stunner. Unfortunately, Brown handicaps himself in a myriad of ways in this book. For example, he notes that if he were able to provide more details on the women he saw that made these experiences so worthwhile, he would have had a stronger book. He's right. The rote, almost robotic nature of the interactions as he depicts them here make him come across as an emotionally stunted, borderline monstrous person. Obviously, there are any number of people in the world of comics who vouch for Brown's sweetness and caring as an individual, but that's neither here nor there with regard to the Brown we see in the text itself. In the book, Brown tries to defend seeing escorts who might possibly have been mixed up in human trafficking by downplaying the likelihood that the scenarios he encountered might have fallen under that category. What cannot be denied is that one young woman he saw was reluctant to see him and was urged to do so by the madam in the room; if that's not sex under coercion, I don't know what is.

There are other critiques of Brown's portrayal of sex to be made. One implied aspect of romantic love is mutual sexual satisfaction. Obviously this does not occur for every couple in every scenario, but a financial transaction by its very nature is supposed to be an investment on the part of the purchaser that their pleasure is the only important part of the transaction, which is a rather limited way to experience sex. Certainly, many escorts advertise "the girlfriend experience" which can imply mutual pleasure, but a world where all sexual encounters were purely financial would be a more tedious and less warm one.

Beyond any critiques of Brown's defense of prostitution and to what degree he draws satisfaction from these experiences, it's his attack on romantic love that I find more interesting and more problematic. There are a number of fascinating exchanges between Brown and his longtime friends Seth and Joe Matt (and the scenes with the three of them are uniformly fantastic), with Seth scoring the most direct hits. When Brown says that he enjoys talking to the escorts makes the experience seem "less cold and impersonal". Seth retorts, "If you want a sexual experience that's not cold and impersonal--get a girlfriend." Later, Brown makes a reasonable point against lifetime ("possessive") monogamy when he says that people change over time, and can't be expected to be compatible in the same way several years into the relationship. When the escort he's with says that if you love you're partner, you'd at least be willing to try to make it work. Brown's reply is truly the heart of his position against monogamy "Romantic love is work. Call me lazy, but I don't want to do the work". What it boils down to is that he's not interested in doing the kind of scary communicating and negotiating with a partner that leaves one vulnerable to being hurt, in exchange for the possibility of strengthening bonds and retaining intimacy. Nor is he willing to risk the possibility of drifting apart and breaking up, with the messy outcomes that involves. That is entirely his right, but using this argument by anecdote to create a universal maxim a la Ayn Rand is astoundingly puerile and in denial of empirical evidence. It denies the existence of romantic love and the potential value of monogamy as he defines it simply because it's too much work for him.

The punchline is that he's effectively monogamous with an escort named Denise. He justifies this by saying that there's no contract tying them together, which is a weak sauce argument given that few marriages stay together simply because of that piece of paper. What is sad in the end is that Brown admits he's not sure Denise would still have sex with him if he didn't pay her, despite the fact that he's her only client at this point. While he derives a certain thrill from being able to have sex with women without the burden of going through social rituals that he's not adept at playing, that thrill has to be blunted by the knowledge that without the financial aspect of that relationship, they wouldn't spend time with him. Brown makes no differentiation between sex and intimacy in this book, nor does he ask himself the question if intimacy is truly possible in a purely financial transaction. If intimacy isn't important to him, it's not his right to declare romantic love to be "evil" if one of its benefits is something he doesn't experience. If it is important to him, how can this be experienced in an escort/john situation? Intimacy involves vulnerability, and vulnerability implies risk. Intimacy implies the possibility of getting one's feelings hurt and hurting someone else's feelings. In other words, it involves the frequently painful aspects of human interactions in a relationship and means that in order to achieve it, a commitment to working for it is necessary. Just because Brown isn't interested in that kind of work doesn't mean the rest of humanity isn't willing to try the frequently painful and frustrating but also often rewarding and fulfilling process of love. Brown is so busy engaging technical and moral arguments about prostitution's legality and existence that these other issues either barely register or are brought up and never engaged. It's a shame, because Brown is otherwise amazingly forthcoming about his desires (in a way that is usually not especially flattering to himself), is clever in his cartooning, and provides many moments of humor.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Notes On The Script: The City Troll

Aaron Whitaker breathes new life into the sad-sack loser/slice-of-life genre with his long-form debut, The City Troll. With page after page of simple, expressive art that emphasizes gesture, movement and body language, Whitaker skillfully moves his characters through a love triangle plot with a number of hilarious and moving twists and turns. The genius move Whitaker makes is to take the central conceit of mopey losers--their navel-gazing insistence that they are the center of their own narrative--and have its protagonist knowingly live his life as though he were a character in a story. The story is this: god capped off his creation by bringing to life The Perfect Man. His name is Ian, and all women fall in love with him and all men want to hang out with him. God grew jealous of his creation, so he cursed The Perfect Man by forcing him to be friends with the most loathsome, disgusting, pessimistic creature, and named it The City Troll.

The City Troll, of course, is the imagined alter ego of Paul, a young man with massive confidence problems who survived living with an abusive mother. Whitaker nimbly moves back and forth from depicting Paul as himself and as the City Troll, depending on his mood and state of depression. It's a clever bit of magical realism that fits smoothly into the narrative thanks to his cartoony drawing style. There's another remarkable scene early in the book when Paul (who doubles as the narrator) describes the possibility of love at first sight as being a combination of one's first girlfriend, the "sixth grade teacher who always smelled like cucumber melon scented shampoo", a quirky indy actress, the image that first provided masturbation fodder and one's mother. That leads him to meet Emily. It's a wonderfully-written and drawn sequence, one that's remarkably evocative, funny and charming.

Paul meets Emily but is too petrified to say anything, and she winds up with Ian. The "perfect man" description is quite apt; early in the book, he has to deal with having two women in love with him at once, then having to figure out how to get out of both of them wanting to be in a polyamorous relationship with him. Despite that, he remains remarkably devoted to his best friend Paul, and vice-versa. Paul suffers in silence as Ian dates Emily and they fall in love, even as Emily and Paul spend time together as screenwriters. That leads to a number of funny scenes where Paul tries to become a better person in order to translate that to one of his characters after Emily lists out that character's flaws. That includes a series of funny scenes with Paul, his father, and his father's new hippie girlfriend (named "Understanding").

Paul eventually does take action to try to win Emily, which leads to a clandestine affair. Paul tries to figure out a way to keep Emily and still stay friends with Paul, but it all blows up in his face. The end of the book contains its own critique, as a character who "wallows around in [his] own misery" isn't going to get the girl--especially when that girl has her own City Troll issues. Whitaker throws those clues in when Emily tries to make excuses for why she goes off her anti-depressants, claiming that they impeded her output as an artist. It becomes clear that she's not well by the end of the book in her own way, and Ian is a victim of the pathologies of two friends. At the same time, Paul eventually learns his lesson and makes tentative moves toward change by the end, even if it's not clear that he's learned how to be less selfish or more empathetic. There's a lot to chew on in this book, which is filled with funny and true-to-life dialogue, odd situations and characters who take on a life of their own. It's one of the more impressive debuts I've seen from a young cartoonist, and I'm excited to see what Whitaker chooses to do next.

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

A Day In The Life Of A City: Denys Wortman's New York

One of my favorite comic art books from the past couple of years is Denys Wortman's New York, a bok that arose thanks to some digging by the head of the Center for Cartoon Studies, James Sturm. Wortman was one of those famously anonymous cartoonists from the first half of the twentieth century who produced a new one-panel comic four times a week for about thirty years. Other than a couple of collections with limited print runs, the strip mostly just disappeared from the public consciousness the way that so many strips are gone and forgotten, byproducts of an ephemeral form of media. Sturm was fortunate enough to get in touch with Wortman's son, who happened to be sitting on a treasure trove of over 5,000 originals by his father. Sturm, along with former student Brandon Elston, took a selection of these strips to form a narrative of sorts. The narrative doesn't follow a particular person, but rather the life of the city itself over the span of just one day. It's an extraordinary solution to the problem of how best to present this material in a way that doesn't drag.

What's interesting about this book is that the quality of the drawings is far better than a book that simply reprinted his work from newspapers or tear sheets would be. The book is shot directly from Wortman's pencils, which have an amazing power and sheer presence. This is a book about the teeming millions: young and old, rich and poor, working and unemployed, on the sidewalks or at the beach. It starts off in the morning, as housewives hang laundry outside their fire escapes and craggy old men rush to the subway. Young women rush to work as secretaries or factory workers, while middle-aged men try to find ways to collect on bills. Though the strips are not printed in anything resembling chronological order, Sturm & Elston still whip us across the city at work: the theater district, the garment district, maids, janitors, executives, and cooks at diners. With much of the strip running through the depression, Wortman shows us people desperate for aid and jobs. There's a jaw-dropping set of strips set in Coney Island, the vacation spot of choice for the working class. Though Wortman worked with a lot of photo references, he still does an uncanny job at capturing the spirit and the motion of so many people. The beach scenes are memorable because they depict huge crowds of people on the beach, on the boardwalk and under the boardwalk (with some poses that must have made the newspaper's censors a little nervous). He captures that sense of people wanting to pretend that they were somewhere exotic, even if every other New Yorker seemed to be there as well.

Wortman was also aces at drawing kids: out on the street, reading comics, running through fountains, and playing macabre games like "electric chair". His understanding of gesture and body language made every strip come alive, and his attention to detail like clothing is especially remarkable. This book is practically a class on New York fashions over a thirty year period, both of the rich and the working-class. We take a peek into classrooms, hospitals, doctor's offices, and beauty salons. We follow shopping trips and pretzel salesmen. We take a look inside the Museum of Natural History (that blue whale has been in the same place for a long time) and see the game from behind home plate at the Polo Grounds. We see the city in the sun and in the rain, go out on the town to dinner and the theater/movies/opera. We follow sailors going dancing and attend many a wild, late-night party. Finally, we see people make their way home, including one man on an empty subway who nonetheless can't help but stand up out of sheer habit.

Most of the captions to the images were written either by Wortman's wife or someone else; they were more capstones to the images than real gags. Some of them don't even try to be very funny--just accurate. The captions help provide some context and flavor for the images, though most of them could easily stand on their own. What I like most about Wortman's drawing is just how intuitive it is. He seems to know just when to use his charcoals to add some fuzz and shading to an image, and when to sharpen his pencil and let certain kinds of details pop off the page. These are not photorealist drawings, nor are they entirely expressionistic. These captions carry their own sense of reality, thrusting the reader into the image and giving one a true sense of what it might have been like to been in that particular moment, to see a wide range of actions unfolding in front of your eyes. The mass of humanity he depicts in page after page creates an imaginary buzz, as the reader imagines what all those people together must sound like. It's a rare art book that turns out to be a page-turner, but that's certainly the case with Denys Wortman's New York, and that's a tribute to the talent of the artist and the vision of the editors.

What's interesting about this book is that the quality of the drawings is far better than a book that simply reprinted his work from newspapers or tear sheets would be. The book is shot directly from Wortman's pencils, which have an amazing power and sheer presence. This is a book about the teeming millions: young and old, rich and poor, working and unemployed, on the sidewalks or at the beach. It starts off in the morning, as housewives hang laundry outside their fire escapes and craggy old men rush to the subway. Young women rush to work as secretaries or factory workers, while middle-aged men try to find ways to collect on bills. Though the strips are not printed in anything resembling chronological order, Sturm & Elston still whip us across the city at work: the theater district, the garment district, maids, janitors, executives, and cooks at diners. With much of the strip running through the depression, Wortman shows us people desperate for aid and jobs. There's a jaw-dropping set of strips set in Coney Island, the vacation spot of choice for the working class. Though Wortman worked with a lot of photo references, he still does an uncanny job at capturing the spirit and the motion of so many people. The beach scenes are memorable because they depict huge crowds of people on the beach, on the boardwalk and under the boardwalk (with some poses that must have made the newspaper's censors a little nervous). He captures that sense of people wanting to pretend that they were somewhere exotic, even if every other New Yorker seemed to be there as well.

Wortman was also aces at drawing kids: out on the street, reading comics, running through fountains, and playing macabre games like "electric chair". His understanding of gesture and body language made every strip come alive, and his attention to detail like clothing is especially remarkable. This book is practically a class on New York fashions over a thirty year period, both of the rich and the working-class. We take a peek into classrooms, hospitals, doctor's offices, and beauty salons. We follow shopping trips and pretzel salesmen. We take a look inside the Museum of Natural History (that blue whale has been in the same place for a long time) and see the game from behind home plate at the Polo Grounds. We see the city in the sun and in the rain, go out on the town to dinner and the theater/movies/opera. We follow sailors going dancing and attend many a wild, late-night party. Finally, we see people make their way home, including one man on an empty subway who nonetheless can't help but stand up out of sheer habit.

Most of the captions to the images were written either by Wortman's wife or someone else; they were more capstones to the images than real gags. Some of them don't even try to be very funny--just accurate. The captions help provide some context and flavor for the images, though most of them could easily stand on their own. What I like most about Wortman's drawing is just how intuitive it is. He seems to know just when to use his charcoals to add some fuzz and shading to an image, and when to sharpen his pencil and let certain kinds of details pop off the page. These are not photorealist drawings, nor are they entirely expressionistic. These captions carry their own sense of reality, thrusting the reader into the image and giving one a true sense of what it might have been like to been in that particular moment, to see a wide range of actions unfolding in front of your eyes. The mass of humanity he depicts in page after page creates an imaginary buzz, as the reader imagines what all those people together must sound like. It's a rare art book that turns out to be a page-turner, but that's certainly the case with Denys Wortman's New York, and that's a tribute to the talent of the artist and the vision of the editors.

Labels:

denys wortman,

drawn and quarterly,

james sturm

Monday, June 11, 2012

Black and White: Nurse Nurse

Katie Skelly's Nurse Nurse is the first book to be published by Sparkplug Comic Books after the death of its publisher, Dylan Williams. Plans for collecting Skelly's original miniseries had long been in the works, pending Skelly's completion of the story. With the boost of an Indiegogo campaign that helped fund a year's worth of books, Nurse Nurse finally made its debut in May of 2012, eight months after the death of Williams and a few months after it was announced that the trio of Virginia Paine (a former Sparkplug employee), Emily Nillson (Williams' wife) and Tom Neely (Williams' close friend) would take over operations of Sparkplug. Skelly noted that Paine did a lot of production work on her psychedelic epic, and it shows in the way that even Skelly's earliest images pop off the page with great clarity. When we reach the more explicitly psychedelic portions of the story, the pages look especially beautiful. I would have preferred them going to a larger page size to truly feature that aspect of the storytelling, but the simplicity of Skelly's line is such that no details are lost going to a digest-sized format.

The comic was inspired in large part by Roger Vadim's film Barbarella, which in itself was adapted by the Jean-Claude Forest comic. Both are essentially complete nonsense, and really act as an excuse to indulge in style as well as T&A. Skelly was not so much inspired by the sexual content of Barbarella but rather its style. Each chapter of the book is a chance to dip into a different set of stylistic flourishes, to the point that in Nurse Nurse, style is substance. The story of vaguely Candide-like outer space nurse Gemma finds her going from one set of perils to the next, just barely staying ahead of doom and/or insanity. She winds up on Venus, where a careless chemist has created a goo spread by the planet's many butterflies that causes those who touch it to become super-horny. She is captured by space pirates, who include a masked woman and a half-woman/half-panda hybrid as well as her ex-boyfriend. She commandeers an escape pod to Mars and winds up with mysterious natives who are hosting the most popular pop band in the universe.She winds up having a bad trip but recovers, only to discover that her likeness is being used in a popular TV show. Investigating further, she is nearly torn to bits by a group of her clones, until she's rescued by her pirate ex-boyfriend. She finally winds up on Earth and simply drops out, laying in a field.

All of those episodic plot points are to be enjoyed on their own, as Skelly throws a kitchen's sink worth of crazy and cute images at the reader. With a very simple and spare line, Skelly tosses in classic psychedelic images, which at its core is all about the ways in which black and white interact with each other. There are a number of pages that reflect that sort of interplay between the two opposites, with figures and background melting into and warping into each other. Skelly is still interested in telling a story, which is why the visuals draw the reader in rather than overwhelm the eye, as a lot of psychedelic art might. Her character designs are simple but effective, drawing in the eye with the use of key details like carefully-placed freckles, odd clothing and body paint. The simplicity of her character design makes the psychedelic quality of her pages all the more effective, since it's still easy to follow the action in every sequence. In addition to character design, character costuming is another important aspect of this comic. In addition to the crisp nurse uniform Gemma wears, the outfits worn by the pirates are a sort of futuristic mutation of 1960s mod fashion. Skelly's use of gesture and body language drives each panel, with character poses that almost look cinematic in their dramatic nature. The overall effect is a breezy, lighthearted, relentlessly strange and amusing narrative that must be accepted by the reader on its own terms. The conspiracy theory and adventure narrative that might have driven other comics are less important in Nurse Nurse than simply enjoying the journey and taking in all the sights.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Great Responsibility: The Death-Ray And Daniel Clowes' Film Career

Daniel Clowes' super-hero story The Death-Ray provoked a lot of very interesting commentary. The two best articles on the subject are from Isaac Cates (published at the time the original source material, Eightball #23, came out back in 2004) and Ken Parille, upon the re-release by Drawn & Quarterly last year. I will address some of those points in bullet-point fashion, but I wanted to start with an observation not many have discussed.

To wit: few critics have addressed the effect that becoming a screenwriter has had on Clowes. While film has always been an obvious influence on his work Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron makes that clear, but the humorous follow-up strip where the Hollywood version of LVG is a huge, embarrassing flop that eviscerates Clowes' original text is interesting in light of him adapting his own material for film. Beyond the psychological and eschatological themes that run through much of Clowes' work, the three issues of David Boring (Eightball #19-21, published annually in 1998, 1999 and 2000) are structurally produced like a three-act Hollywood script. There are so many film-related trappings in this comic that I could film an entire column, but the film-poster cover of Eightball #21 lays it all bare. These comics were created at roughly the same time Clowes was writing the script and working with Terry Zwigoff on the film version of Ghost World. The infatuation with film so present in this comic may well reflect Clowes' creative enthusiasm in writing the script and seeing it come to life in such a satisfying way.

Conversely, the reality of distributing and promoting a film as well as the all-encompassing nature of its release, may well have had a significant impact on the creation of Ice Haven, originally released as Eightball #22. Regardless of the motivation, it seems obvious to me that Ice Haven is a reaction to film as Clowes endeavors to put the language and feel of the comic into very comic-book terms. It's as anti-cinematic a comic as I can imagine, fracturing the narrative and look of the comic into newspaper-style strips. There are frequent narrative digressions into killer bunny rabbits and cave men that have nothing to do with the temporal narrative but have significant connections to the emotional narrative that moves in a straight line from strip to strip. More to the point, the character of Vida (the struggling zine writer who proves to be kidnapper Random Wilder's poetic nemesis) is about to quit writing when "a phone call came from Hollywood!" Improbably, she was "being summoned immediately to work on a big movie project!!" She promises to "be the biggest, richest, most popular writer in history! You just watch dear reader, I'll be the biggest whore ever!" It doesn't seem to be too much of a leap to see this as a sardonic autobiographical statement about how Clowes felt as an artist while working in Hollywood, especially as he started to take on work that wasn't based on his own comic.

Still, there's a joy at work in Ice Haven that celebrates the language of comics and the way it can easily mash up genre, obscure language, and convey meaning in ways no other art form can. It's still his master work in my opinion, as his formal command of comics is dizzying and his characterization is rich, complex and frequently hilarious. People tend to forget just how funny Clowes can be, and Ice Haven displays his merciless sense of humor at its sharpest. The central conflict of Ice Haven winds up having no teeth, as even the kid who seems like a thug is just all talk. It's all a put-on, a joke Clowes shares with himself and the reader as he makes you do a little bit of work in deciphering the text.

By contrast, The Death-Ray feels uglier and more cynical. It was originally the 23rd and final issue of Eightball, and it feels like a coda of sorts to a certain body of work. Isaac Cates said in his article that the critic Sean Collins said that this book isn't so much a super-hero story as it is the origin story of a serial killer. After the success of the film version of Ghost World, Clowes followed that up with Art School Confidential, an ugly and cynical film that was a huge critical and commercial bomb. If Ghost World represents a film that accurately conveys the spirit of the original and substantive source material, then Art School Confidential represents a film made from the slightest of source material (the original short story is more a rant than an actual narrative) dressed up with an absurd serial killer plotline. Sure, Clowes pokes fun at this with the metatextual commentary of the filmmaker in the story doing something sillier, but the fact is that Clowes wrote a serial killer movie. In his own parlance, he perhaps "became the biggest whore ever!" There are things to recommend in this film, not the least of which is the daring choice of making every one of the characters completely despicable by the end of the film. The character of Andy from The Death-Ray even reminds me a bit of Jerome, the protagonist of Art School Confidential: at the beginning of each story, they are naive if alienated. By the end, they have completely shed any pretense to moral or ethical behavior as a result of being buffeted by the forces surrounding them. Something in them simply snaps, and when they cross the line, there's no coming back.

Steeping The Death-Ray in the language of comics and Steve Ditko's Spider-Man in particular creates a tension between the exaggerated ethical struggles Spider-Man found himself faced with and the fact that Andy and his sidekick/instigator Louie had to create all of their own struggles. In both cases, the "heroes" triumph because of their superior application of violence rather than the correctness of their own moral position. Unlike Spider-Man, and because of the uniquely brutal nature of his titular weapon, Andy only occasionally feels pangs of guilt. He gets to decide who lives and who dies, a power that would overwhelming for anyone, much less the typical Clowesian alienated loner desperate to make connections. Like Steve Gerber's Foolkiller character, the line between "evil" and annoying behavior is a thin one--is it just to murder a jaywalker or litterer? There are no good or evil characters in this story, per se, just frustrated and angry people. Or perhaps, there are no heroes to be found, but plenty of Marvel-style villains: misunderstood misanthropes who lash out after a lifetime of abuse or neglect, paying back their misery a thousandfold when they find themselves with powers. Louie is clearly the protagonist of his own story (as are all teens) but winds up acting as a sort of malicious Greek chorus for Andy, pushing him and pushing him to act so as to fulfill his own dark and juvenile urges until Andy finally does it. That's when he understands that there's a line, and that he's pushed Andy across it, and there's no turning back now. There is no justice, no retribution, no resolution. Even Clowes teases the reader with a "choose-your-own-adventure" ending, with a couple of them winding up as typical genre resolutions and the third being in line with the rest of the book: Andy keeps living his life and occasionally "falls off the wagon" and kills some more people for ridiculous and selfish reasons. It's not surprising that Clowes' later comics (Mister Wonderful in particular) were far more in touch with humanity and connecting with others in a successful manner (despite many pitfalls); The Death-Ray represents Clowes at his darkest, most cynical and most grim, and I don't blame him for not wanting to return to that place anytime soon.

To wit: few critics have addressed the effect that becoming a screenwriter has had on Clowes. While film has always been an obvious influence on his work Like A Velvet Glove Cast In Iron makes that clear, but the humorous follow-up strip where the Hollywood version of LVG is a huge, embarrassing flop that eviscerates Clowes' original text is interesting in light of him adapting his own material for film. Beyond the psychological and eschatological themes that run through much of Clowes' work, the three issues of David Boring (Eightball #19-21, published annually in 1998, 1999 and 2000) are structurally produced like a three-act Hollywood script. There are so many film-related trappings in this comic that I could film an entire column, but the film-poster cover of Eightball #21 lays it all bare. These comics were created at roughly the same time Clowes was writing the script and working with Terry Zwigoff on the film version of Ghost World. The infatuation with film so present in this comic may well reflect Clowes' creative enthusiasm in writing the script and seeing it come to life in such a satisfying way.

Conversely, the reality of distributing and promoting a film as well as the all-encompassing nature of its release, may well have had a significant impact on the creation of Ice Haven, originally released as Eightball #22. Regardless of the motivation, it seems obvious to me that Ice Haven is a reaction to film as Clowes endeavors to put the language and feel of the comic into very comic-book terms. It's as anti-cinematic a comic as I can imagine, fracturing the narrative and look of the comic into newspaper-style strips. There are frequent narrative digressions into killer bunny rabbits and cave men that have nothing to do with the temporal narrative but have significant connections to the emotional narrative that moves in a straight line from strip to strip. More to the point, the character of Vida (the struggling zine writer who proves to be kidnapper Random Wilder's poetic nemesis) is about to quit writing when "a phone call came from Hollywood!" Improbably, she was "being summoned immediately to work on a big movie project!!" She promises to "be the biggest, richest, most popular writer in history! You just watch dear reader, I'll be the biggest whore ever!" It doesn't seem to be too much of a leap to see this as a sardonic autobiographical statement about how Clowes felt as an artist while working in Hollywood, especially as he started to take on work that wasn't based on his own comic.

Still, there's a joy at work in Ice Haven that celebrates the language of comics and the way it can easily mash up genre, obscure language, and convey meaning in ways no other art form can. It's still his master work in my opinion, as his formal command of comics is dizzying and his characterization is rich, complex and frequently hilarious. People tend to forget just how funny Clowes can be, and Ice Haven displays his merciless sense of humor at its sharpest. The central conflict of Ice Haven winds up having no teeth, as even the kid who seems like a thug is just all talk. It's all a put-on, a joke Clowes shares with himself and the reader as he makes you do a little bit of work in deciphering the text.

By contrast, The Death-Ray feels uglier and more cynical. It was originally the 23rd and final issue of Eightball, and it feels like a coda of sorts to a certain body of work. Isaac Cates said in his article that the critic Sean Collins said that this book isn't so much a super-hero story as it is the origin story of a serial killer. After the success of the film version of Ghost World, Clowes followed that up with Art School Confidential, an ugly and cynical film that was a huge critical and commercial bomb. If Ghost World represents a film that accurately conveys the spirit of the original and substantive source material, then Art School Confidential represents a film made from the slightest of source material (the original short story is more a rant than an actual narrative) dressed up with an absurd serial killer plotline. Sure, Clowes pokes fun at this with the metatextual commentary of the filmmaker in the story doing something sillier, but the fact is that Clowes wrote a serial killer movie. In his own parlance, he perhaps "became the biggest whore ever!" There are things to recommend in this film, not the least of which is the daring choice of making every one of the characters completely despicable by the end of the film. The character of Andy from The Death-Ray even reminds me a bit of Jerome, the protagonist of Art School Confidential: at the beginning of each story, they are naive if alienated. By the end, they have completely shed any pretense to moral or ethical behavior as a result of being buffeted by the forces surrounding them. Something in them simply snaps, and when they cross the line, there's no coming back.

Steeping The Death-Ray in the language of comics and Steve Ditko's Spider-Man in particular creates a tension between the exaggerated ethical struggles Spider-Man found himself faced with and the fact that Andy and his sidekick/instigator Louie had to create all of their own struggles. In both cases, the "heroes" triumph because of their superior application of violence rather than the correctness of their own moral position. Unlike Spider-Man, and because of the uniquely brutal nature of his titular weapon, Andy only occasionally feels pangs of guilt. He gets to decide who lives and who dies, a power that would overwhelming for anyone, much less the typical Clowesian alienated loner desperate to make connections. Like Steve Gerber's Foolkiller character, the line between "evil" and annoying behavior is a thin one--is it just to murder a jaywalker or litterer? There are no good or evil characters in this story, per se, just frustrated and angry people. Or perhaps, there are no heroes to be found, but plenty of Marvel-style villains: misunderstood misanthropes who lash out after a lifetime of abuse or neglect, paying back their misery a thousandfold when they find themselves with powers. Louie is clearly the protagonist of his own story (as are all teens) but winds up acting as a sort of malicious Greek chorus for Andy, pushing him and pushing him to act so as to fulfill his own dark and juvenile urges until Andy finally does it. That's when he understands that there's a line, and that he's pushed Andy across it, and there's no turning back now. There is no justice, no retribution, no resolution. Even Clowes teases the reader with a "choose-your-own-adventure" ending, with a couple of them winding up as typical genre resolutions and the third being in line with the rest of the book: Andy keeps living his life and occasionally "falls off the wagon" and kills some more people for ridiculous and selfish reasons. It's not surprising that Clowes' later comics (Mister Wonderful in particular) were far more in touch with humanity and connecting with others in a successful manner (despite many pitfalls); The Death-Ray represents Clowes at his darkest, most cynical and most grim, and I don't blame him for not wanting to return to that place anytime soon.

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Total Immersion: Daybreak

Brian Ralph came to prominence with the publication of Cave-In, a wordless story that followed the adventures of a monkey-like character exploring an underground kingdom. It was the clearest distillation of the Fort Thunder group of artists inspired by video games, role playing games, super hero comic books and fine art, wherein the environment is every bit as important as the characters, if not more so. Daybreak (originally published as a series of three magazine-sized comics by Bodega) transplants this aesthetic to the zombie genre, thrusting the reader into the story by making them a silent character whose first-person view dominates the story. In this manner, Daybreak mimics the action of a first-person shooter where one's character avatar is entirely off-screen.

What makes the book such a chilling read is that most of the action, and the zombies themselves, are also seen off-screen. We only get shadowy views of the monsters and charred arms and legs sticking through doors and windows. There is no explanation given as to what caused their emergence or how the world got to be the way it is. It's simply assumed that the reader understands what's going on, and this implied understanding cleverly dovetails with Ralph's skill in quickly bringing a reader up to date with exactly what's at stake in the first few pages of the story. We're introduced to our fellow protagonist, a cheery one-armed man who graciously shares his possessions with you as you move from one charred, burnt-out environment to the next. Every panel is filled with rubble, broken objects and just plain stuff--the detritus of civilization.

Ralph slowly amps up the action as we learn that it's our fellow humans that are the real cause of concern, not just zombies. Ralph heightens tension with any number of tricks: a driving rainstorm that darkens each panel for several pages. We tumble around the page as a car the one-armed man is driving with you in it tumbles over and over after an accident. The unseen protagonist and their friend are captured by a lunatic who plans to feed them to his "family", a group of zombies he had in his attic. The one-armed man is bitten, leaving the reader/protagonist with a horrible decision to make: when do they kill their former friend? The final page is especially unsettling, because it's unclear just how far along the one-armed man is in becoming a zombie, as we see his facial expression change subtly from panel to panel in a manner that suggests the spark of humanity is still in his burnt-out eyes--but for who knows how long?

Backstory is irrelevant here, because the only narrative that matters is being alive. The question that Ralph poses is what does humanity mean in a world that's the apotheosis of Thomas Hobbes--nasty, brutish and short? With no laws and no rules, what does ethics mean in this world? Ralph suggests that one's choices while one is still human are the only thing that matters. The one-armed man still wound up as a zombie despite his generosity, but at least he wasn't a head-toting lunatic like the man who tried to kill him with his "family." Ralph puts the reader through the wringer in scenes where the unseen protagonist is wandering around in the dark with a flashlight before discovering a gang of zombies after he spies only their legs. The frequently silent storytelling approach is doubly immersive: we are immersed in this world thanks to the details in each panel, and we are immersed in how to negotiate this world thanks to panel-to-panel transitions, black-outs, and quick cuts. Ralph's storytelling is absolutely masterful, filling the reader with dread and fear even as he injects moments of hope and black humor, alternating between blindingly quick moments of violence and languid looks around the environment. When the unseen protagonist is unconscious, the story goes on without them, a disorienting but effective technique that helps break tension at particular junctions while resetting it at the same time.The tiniest victories have a great resonance in this story, even as each defeat feels like a harbinger of inevitable doom. The six panel grid works nicely to keep the pace of the story steady, though I did miss the bigger pages of the original comic.

What makes the book such a chilling read is that most of the action, and the zombies themselves, are also seen off-screen. We only get shadowy views of the monsters and charred arms and legs sticking through doors and windows. There is no explanation given as to what caused their emergence or how the world got to be the way it is. It's simply assumed that the reader understands what's going on, and this implied understanding cleverly dovetails with Ralph's skill in quickly bringing a reader up to date with exactly what's at stake in the first few pages of the story. We're introduced to our fellow protagonist, a cheery one-armed man who graciously shares his possessions with you as you move from one charred, burnt-out environment to the next. Every panel is filled with rubble, broken objects and just plain stuff--the detritus of civilization.