On the book's spine, Shaw bills his story as "family/comedy/drama/horror/ mystery/romance", and it indeed has all of these elements--with "family" being a good catch-all to to describe the book in a nutshell. Focusing in on a final family reunion shortly after David & Maggie Loony have very matter-of-factly informed their children that they were going to divorce after 40 years of marriage, the book is a microscope on how families do (and don't) work, with a number of horrific and laugh-out-loud moments. There isn't a real plot, per se, but rather a series of individual emotional arcs that have varying degrees of resolution. That lack of plot is acutely felt by the characters themselves, who try various activities as a way of dealing with (or not dealing) with this announcement. It's also reflected and amplified by a number of background elements, including a TV show following a celebrity couple's rise and fall and the plot of a movie seen by a couple of the characters.

Let's set the stage for this story. David and Maggie live in a house by the beach and apparently rarely see their children. Neither of them are big talkers and are both clearly creatures of routine. Dennis is the oldest, someone who never quite lived up to his youthful studly potential as an athlete. He's married to Aki and they have a toddler son, and it becomes quite evident early in the book that their marriage isn't exactly on the strongest of footings (but perhaps not evident to Dennis himself). Claire is the middle child, who came along with her 16-year-old daughter Jill. Being a teen, Jill is constantly mortified by her mother. Claire married and divorced at a young age and clearly has had a difficult time separating her youth from her responsibility as an adult. Peter is the youngest child, a quiet loner/loser who always felt out of place and isn't close to his father.

Shaw brilliantly introduces the family through a brief series of flashbacks using one of his clever repeating motifs. The motif that recapitulates the theme most succinctly is that of sand. The house is at a beach, and Shaw begins the book by talking about different kinds of sand and then segues into talking about different types of Loonys; that is, different incarnations of the Loony family as a unit, each of which has its own importance. At this point in time, however, "Black Hole Loonys" takes precedence--a state where there is no family, only individuals. Like sand, it's a vast tapestry (across time especially) whose unity is illusory: it's really composed of tiny particles. Shaw also makes use of another common element in his work: the schematic drawing. In particular, we see a number of drawings and plans of the Loony house as part of the narrative (one of many ways Shaw jars the reader). These plans serve multiple purposes in the story: for Dennis, it's a key to solving a mystery; for Maggie, it's a way of compartmentalizing her life; as a narrator, it's a way of providing small emotional clues.

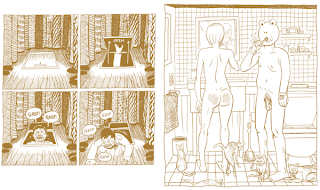

Shaw subverts both the expectations of the reader and his own characters. The most restless characters hope that their plans for activity will somehow improve things or solve mysteries; instead, they are met with failure and humiliation. The passive characters somehow find their way into new lives, only becoming active when they're not trying to actively impose their will on their situations. Showering/washing is another active motif in this story, as various characters use it as a sort of springboard for potential attempts at renewal that don't stick. The active characters above all else are trying to create meaning: Dennis frames the week as a mystery (complete with secret keys and strange maps), Claire and Aki hoping for a magical encounter in town that will relieve them of their ennui, Jill is desperate to be an adult. Yet they find that these attempts just lead to emotional dead ends. Let's now focus in a little closer on the emotional arcs of each major character, since this individual view plays into how Shaw tells his story:

Dennis: His parents divorcing provokes a reaction that is entirely self-absorbed because he's only wrapped up in how he feels about it. Specifically, he's (rightly) worried about the stability of his own marriage but can't grapple with this on a conscious level. With that total lack of self-awareness, he seeks to frame the divorce as a "mystery" that must have some solution, so that he his own marriage can be saved. The physical wounds he incurs (and ignores/hides) in the story are apt metaphors for his inability to acknowledge his own vulnerability. It's no accident that Shaw drew him with Homer Simpson five-o'clock-shadow: he's a buffoon he thinks he's an alpha-male, a "self-parody" as his sister put it. He only accesses his real feelings entirely by accident (after a fainting spell) and even then pawns them off on what he thinks his mother must feel. His wife, petrified, finally understands her husband at that point and perhaps starts to feel a little guilty for the first time. It was strongly implied that she had been cheating on him and was perhaps ready to give up on their marriage, lying to herself and him. When Dennis reaches out to his father and invites him to live with his family, it's both a generous gesture and unconscious attempt to save himself and his family (if he can save his father, then he will therefore save himself)--and Aki perhaps understands this.

Peter: The visual depiction of Peter as Mr. Toad is an understated stroke of genius. Shaw spells it out only toward the very end that this has always been his self-image as the family's quiet outsider. He's filled with self-loathing and alienation, yet there's also a certain kindness, affection and generosity of spirit that he possesses that's not present in the rest of his family. His courting of a local nanny named Kat whom he meets at the beach is hilarious and sweet, unlocking some of his potential. Still, his emotional alienation immediately arouses his latent feelings of paranoia and insecurity, as he's on the lookout for clues, mysteries and conspiracies. Typical of an immature person, he smothers his object of affection when finally given an emotional outlet. After being together for just a day, he tells her that he's fallen in love with her. Of course, their relationship is a transient one (something he doesn't fully comprehend till it's over), but the experience has not only altered his relationship with his family (for the better), but it's transformed him. The most passive character in the book wound up developing the most, even if he was sort of goaded into that development. The way Shaw makes him both hilariously inept (the scene where he masturbates watching TV, cleans up using a cloth on a table that turns out to be his mother's knitting, and then tosses the whole thing out of a window in embarrassment is fantastic) and poignant is one of the most interesting ways in which he subverts reader expectation.

Claire and Jill: One has to examine both of them at once, because they are mirror-images. Jill is about the same age her mother was when she got married. Her husband was an artist who couldn't handle having a kid and so he split. That rejection still haunts her, preventing her from maturing. Claire and Jill are both alienated and disaffected from their environments, and both are obviously frightened how much they can relate to each other on this level. Claire doesn't want to admit that she's that alienated and puts on the pose of "perfect mom", while Jill can't see that her mother has gone through and that she is going through experiences similar to her, and so they both pretend that they're not anything alike. That is, until they're forced to realize that they are. One major similarity is the difficulty they have with men and male affection. Claire grew up in fear of her father, while Jill grew up without the benefit of a strong male presence. The scene in which both women deal with potential suitors is one of the most gripping and sad in the book, as both quickly lose control of their environments in hilarious and pathetic fashion. In the end, each character gives the other a better understanding of their selves. Neither character is any closer to happiness, but they perhaps understand why they're not happy a bit more.

David and Maggie: Understanding one's parents can be very difficult, especially when neither one is especially expressive or communicative with their children. In this story, neither one cares to talk much about their decision, other than saying that "they were no longer in love with each other". Dennis probes into their old love letters, finding one letter written entirely in code. It was written thus because Maggie's father hated David, so he wrote her in code when he was in the military. The latter is actually pretty easy to decode, as David has trouble finding the words for his first love letter, eventually telling her how much he loves her "bottomless belly button". What's striking about the letters is the sense of longing for each other they evince. When the couple separates at the end of the story, there's finally an understanding that they'll miss each other. The unanswered question here is, will they miss their routines together, or each other? It became clear that both had long settled into being individuals and not a couple. Maggie saw the world as a set of rituals and chores, sometimes desperately attempting to draw a deeper meaning from coincidental events. David had stopped trying to think about what he was going to do next, moaning that he was going to die soon.

Shaw's line and approach is fairly restrained in Bottomless Belly Button. He mostly sticks to six-panel grids, only popping the reader out of this pattern when he shows us photos, diagrams, letters, clippings, etc. or else when he wants to accelerate the action (emotional or physical). His characters all have a touch of the grotesque about them, which is fitting because Shaw's stories have always had a visceral quality to them. That quality helps establish the humanity of his characters even as he uses a sketchy quality in his line. There were times that I thought he got almost too conservative in some of his choices in this book as a sort of trade-off for greater accessibility, especially in terms of the visuals. That said, it was an understandable decision in what was obviously his most ambitious work to date and a clear candidate for book of the year.

No comments:

Post a Comment