Thursday, December 17, 2015

Emergency High-Low Fundraiser

I've taken a bit of a hiatus to start to backfill the 30 Days of CCS feature, but I wanted to see if any readers were interested in helping with an emergency fundraiser. I need to raise a couple of hundred dollars to help bridge through a tough time. Any readers who would care to even make a small donation, it would be enormously appreciated. Thanks to all who read this blog, this year and the many years it's been in existence. There's a paypal button to the right for those who care to donate. Thanks in advance.

Saturday, December 5, 2015

Thirty Days of CCS #35: The Comics Journal on CCS

This article was originally published in The Comics Journal #301 (2011).

Cartoonists Leading Cartoonists: The Trials and Rewards of Getting Mentored By The Likes of Alison Bechdel, Jeff Smith, Stan Sakai, R. Sikoryal, Jesse Reklaw, Denis Kitchen, Tom Hart, Dylan Horrocks David Macaulay and Evan Dorkin, by Robert Clough.

Matt Aucoin was always anxious to hear back from his senior thesis advisor, Stan Sakai, because "I would wonder how bad I messed up each time. But that's the same with every critique. Stan was always so polite when he gave a critique, that it was never disheartening. Stan was also very patient with me." At the Center for Cartoon Studies, the nature of each student-mentor interaction is different for each artist, but it seems that nearly every artist wants the unvarnished truth. "He asked me flat out, 'How much feedback do you want me to give you on your work?' I told him, 'I want it all, everything you've got.' Stan let out a long sigh and then jumped into all the holes I had with [my comic] Die, Baby, Die! He understood what I was going for, but I had sorely missed the mark on my first draft. He added a few scenes and told me how he would tell that story."

Having a mentor is a rare opportunity for young cartoonists to hone technical aspects of their craft that they might not have had the opportunity to either develop on their own or in a larger classroom setting. "I felt that Stan's strong points were my weak points as a cartoonist, and I wanted to work on those as much as I could in my senior year. Stan's great at lettering, storytelling, page layout, composition, perspective and pacing. I wanted to be great at those things too." Going into specifics, Aucoin said, "He would tell me the panels that worked and let me know of the ones that didn't. He would even go so far as to print out my pages, draw all over them, and send them back to me. This was a real treat, getting to see Stan draw my characters in his style. At first, I didn't want to redraw the panels and told him so. After thinking about it, I realized that he was right and ended up redrawing every panel he suggested. Stan was the kind of advisor who told me everything I did wrong, but in such a gentle manner that I never felt put out. After getting feedback from him, I was ready and excited to go back to the drawing board."

Interviewing nearly two dozen graduates of CCS, I discovered the quality of the student-advisor relationship tended to vary widely. Sometimes a negative experience was the fault of an advisor was wasn't prepaed to commit the sort of time and effort that a motivated student would need. Sometimes students were inadequately organized and didn't follow through on their commitments. On other occasions, students and advisors simply weren't appropriate matches on an aesthetic and sometimes personal level. Every graduate had different advice for future students on how best to make this relationship work, but Aucoin hit the nail on the head when he said, "The ball is mostly in the student's court. If you can't produce work for your advisor to critique, they can't critique your work. If you don't tell them what kind of feedback you want an need, they might not give it to you."

Creating Cartoon College

Teaching cartooning at a university level is not a new idea. Indeed, the School of Visual Arts was co-founded by legendary cartoonist Burne Hogarth. There are a handful of other institutions where one can learn how to become a cartoonist, like the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) and the Minneapolis College of Art & Design (MCAD). Those schools offer cartooning and illustration programs as individual majors that are part of a more diverse curriculum. Then there's the Kubert School Of Cartoon & Graphic Art, a trade school that seeks to train the next generation of genre artists.

The expanded curricula from these schools has been a response to the rising demand by young cartoonists for formal education. Whereas art schools used to sneer at comics as an art form (one is reminded of Daniel Clowes' classic short story "Art School Confidential"), such pedagogy has now become much more widely accepted. The fact that such highly regarded cartoonists as Gary Panter, Zak Sally, David Mazzucchelli, and Carol Tyler are faculty members at various art schools and universities is a testament to how seriously those institutions have responded to this demand. That said, the cartooning programs at these schools are a small part of those institutions' overall scope. To a certain degree, the schools had to adjust to the demand by expanding programs, rather than building a cartooning program from the ground up. There wasn't an art school whose sole focus was on comics--not animation, not illustration--until quite recently.

In 2005, cartoonist James Sturm and designer Michelle Ollie founded the Center for Cartoon Studies in the small town of White River Junction, Vermont. Sturm had been a professor at SCAD and Ollie at MCAD, and they pooled their collective experiences to create a vision of a pedagogy for comics that sought to provide training and guidance for young cartoonists, pushing them to put theory into practice right away. What at first appeared to be a quixotic notion has now blossomed into a successful enterprise, thanks to the generosity of state and local governments and the kindness (& resources) of dozens of important figures from the world of comics. (Full disclosure: TCJ publisher Gary Groth is a member of the school's advisory board.) Indeed, what sustained CCS through its earliest months was a sound business plan that attracted investors. A look at its board of directors includes publishers, local businesspeople, non-profit experts and academicians. After years of experience as educators, it was obvious that Ollie & Sturm put a great deal of thought into this endeavor.

While the school is not accredited (a drawback that prevents them from being able to offer federal loans to students), it has been granted the ability to offer MFAs. This has no doubt helped them in getting more prospective students to apply, given the promise of a degree that might help them earn future positions in academia. Wisely, Ollie & Sturm decided to open CCS up to those who did not have college degrees, allowing for a more diverse student population. Those accepted for the two-year MFA program were welcome with a degree in any academic discipline; no previous training in art was required or expected. From the very beginning, Sturm made it clear that he viewed cartooning, storytelling and drawing as distinctly separate but related skills. That's certainly reflected in the first-year courses, which all students are required to take. It was also clear that he thought all three could be taught to highly-motivated students.

The initial founding of the school drew mixed reactions in the world of comics. Some observers sneered at the idea of paying $30,000 to learn how to make minicomics. A few veteran artists scoffed at the notion of formal education being needed to learn how to become a cartoonist. So many members of the underground and early alt-comics generations were self-taught that they viewed this as the best way to learn the craft. They possessed a sense of the artist as rugged individualist, making comics solely to please themselves. The idea of submitting to someone else's idea of what making a comic should be and being judged on it at a formal level was perhaps anathema to them. At a deeper level, this critique of CCS is more about comics as a manifestation of the cultural zeitgeist than it is about actually learning how to become a cartoonist. For many artists of the underground era, comics were their way of expressing themselves within the greater counter-cultural framework. For the generation that came to prominence in the early 80s, many saw comics as an extension of the DIY punk rock ethic, with the Hernandez brothers being the most prominent example. I would contend that it wasn't until what I refer to as the Xeric generation of artists in the 1990s that the idea of outside guidance and assistance became an acceptable part of the culture, a concept that became further entrenched with the rise of alt-comics conventions like APE and SPX in the late 90s.

While those conventions have a distinctive DIY flavor to them, they've also spawned a new generation of cartoonists eager to be inspired by their peers as well as their elders. What's interesting about CCS is that it's captured the intimacy and community of these convention experiences and has fused it with an intense, demanding curriculum where one is pushed by one's peers as much as one's teachers. In detailing the difference between CCS and other art schools, faculty member Robyn Chapman said "Probably the most significant difference is size. We only accept 24 students each year. That class of 24 is a very tight community. They all take the same classes, together, for 2 years. Outside of the classroom, they spend a lot of time together drawing, and also watching movies, playing board games, partying, even playing sports - all the normal social activities of college students. But with a lot more drawing."

"As a community, they learn a lot from each other, and they push each other to do their strongest work. The community here is key. I went to SCAD, at that point I think there were a few hundred students in the Sequential Art program. Most of them I never knew, and the few I knew, I didn't know very well. Here, you know all your classmates pretty intimately. [Fellow faculty member] Steve Bissette has used the word "tribe" to describe the unique community here. I think it's apt."

The CCS Curriculum and The Thesis Advisor

The first year curriculum has been described by Sturm as a "cartoonist boot camp". Each student takes a drawing class (with a life drawing session), a history of comics survey, a cartooning class, a writing workshop and also participates in visiting-artist seminars. Those have ranged from genre artists to children's book illustrators to minicomics stalwarts to the cream of the alt-comics set. While drawing is obviously crucial in this program, there's an understanding that cartooning itself is a kind of writing and can't be reduced to simple draftsmanship. While this approach is not unique, what is unusual is their early focus on design and publication. Chapman notes, "CCS understands that comics is a publishing art. This may sound basic, but this point is missing from some cartooning programs. Some cartooning programs tend to dissect the medium into its more superficial aspects and focus on methods and techniques. CCS is focused on telling stories and making books. From day one, our students are self-publishing."

The second year at CCS, for those who choose to take it, is as loose as the first year is regimented. The thesis project, to quote materials from the school, is "at the heart of CCS's second year curriculum" and "should reflect two semesters' worth of exploration, culminating in a well-constructed final project." That project is evaluated on the content itself, presentation and the work in context with the amount of time spent on it. The thesis determines a passing or failing grade and so carries with it an enormous amount of pressure, although this is to be expected at any kind of graduate program. During the year, each student meets regularly with both faculty and peers to evaluate works-in-progress in an effort to keep everyone on track. The tight-knit nature of this community, further aided by the lack of distractions in the tiny railroad town of White River Junction, means that no one is forgotten. In addition to these measures, each student is expected to pick a thesis advisor, usually from outside of the school.

As Sturm notes, it is hoped that the advisor will help the student with "the nuts and bolts of their cartooning" but also add "insight as to what it takes to make cartooning the center of their life going forward." Michelle Ollie described their role as offering "the benefit of another outside perspective, a point of feedback, extending beyond the interaction with the core faculty of the program and peers." I communicated with two dozen graduates and a handful of advisors about this experience and what it meant to them. That relationship, in many ways, reflected the nature of the thesis process itself, because it forced students to create their own schedules and deadlines and learn how to work with other professionals. Sturm said "The advisors aren't responsible for whip cracking or grading or anything like that. The onus is on the student to produce work for the advisor to respond to. Every advisor/student relationship is different. [For] some it's a week-to-week engagement, for others it's once or twice a semester. All depends on what makes the most sense to the individual personalities involved."

While Sturm said that the feedback for this process has been "mostly positive", he did note that "sometimes advisors drop the ball; they get too busy with deadlines or on tour or just don't make the proper time for whatever reason." Given that this is a paid position (a prospect that advisors Jesse Reklaw & Evan Dorkin both noted was a significant inducement), there's a risk involved in investing in services that may well not pan out for the students. Chapman notes that CCS understands this possibility and plans around it: "The nature of the thesis advisor relationship depends on the dedication of both parties, the student and the advisor. Sometime that dedication is not adequate – both students and advisors have been guilty of this in the past. That is a reason that advisors are only required to commit to one semester. If the relationship is not working, they can choose to end it after one semester. The same goes for students - if they are not satisfied with their advisor, they can select a new one after one semester."

The Perils of The Advising Process

One thing that became clear in the course of these communications is that picking an advisor was more of an art than a science. For every glowing description of how much their advisor helped them, I also heard stories about advisors who were impossible to track down. Some students had radically different experiences with the same advisor. For example, CCS graduates Sean Ford and Laura Terry both had Alison Bechdel as their advisor in different years. Terry was absolutely effusive in her praise for Bechdel and her commitment. After an initial face-to-face meeting (a rarity in this process), Terry set up a "rigorous schedule" with Bechdel, sending a package with her work-to-date on a weekly basis during the first semester. Terry said "Every two weeks we phoned or Skyped and there were occasional emails between us. Her criticism was always apt, and she let me know what was working, what wasn't working, and always guided me towards the right path, but was never didactic."

On the other hand, when Ford chose Bechdel a couple of years earlier, he found that "she was incredibly busy with Fun Home and working on her next book for Houghton Mifflin and didn't have a ton of time to respond to emails." When asked what advice he might give to future students about the process, he concluded it by saying "Don't pick someone who had a book just come out that's forcing them to do book tours. Seriously." Fellow graduate Colleen Frakes echoed this, as both of the advisors she selected wound up going on book tours during her senior year. She still got a good bit out of her brief contacts, as Jeff Smith advised her to "Figure out how the story is going to end before you start it", noting, "You look smarter that way." The input from her second advisor led her to scrap her initial thesis idea. Given that her eventual thesis project led to a Xeric grant, that was sage advice indeed.

While the needs of each student and the styles of each advisor differed, a few trends emerged in the responses I received. Choosing one of your personal heroes as an advisor wasn't always a good idea. Some of them simply didn't have the skills or temperament to excel as an advisor in some cases, while in other examples the student was too starstruck to establish a real working relationship. One graduate who preferred to remain nameless chose a well-regarded underground legend as their advisor and found that their styles and personalities clashed to the extent where nothing was gained from the relationship. Sturm said that he tries to "steer students away from some cartoonists, who despite their wonderful work, may not make such great advisors. I also make thesis advisor suggestions even if the student is not necessarily familiar with the work of that artist." The most-praised advisors tended to be those that either had experience as educators (like Tom Hart) or editors (like R.Sikoryak).

In the case of 2009 CCS graduate Jeremiah Piersol, he had "a lot of difficulty choosing an advisor", wanting someone who would "understand my point of view, and wouldn't push me in a direction of making my work more refined, commercial, etc". Sturm recommended Sikoryak, and Piersol said "His suggestion turned out to be golden." Piersol made an interesting distinction in relating his experience, saying the process "shouldn't work as an apprentice or mentorship situation like it did, for example, with the old masters of the Renaissance." Instead, Sikoryak guided him in "observing and understanding my own work in new ways that I may not have figured out on my own." In technical terms, he found Sikoryak's understanding of cartooning to be especially valuable, particularly "an emphasis on consistency. Sometimes the same character would look different panel to panel in my work, and with his feedback I recognized this." He emphasized that "having R.Sikoryak as an advisor also made me a hell of a lot less lazy as a cartoonist."

2010 graduate G.P. Bonesteel had a similar experience with Sikoryak, taking him as an advisor at Sturm's suggestion after his first advisor didn't work out for him. Sikoryak zeroed in on his character relationships, noting that they talked to the "camera" instead of each other. Bonesteel said that the reason he did this "was one part laziness and two parts lack of confidence in my own abilities" but this comment "really stuck with me because it's true and will make my work stronger". Both he and Piersol urged fellow students not to pick someone famous because "you love their work and want to meet them" or "attach yourself to someone with a big name, because they have a big name". Piersol further urged them to "go in with a direction", thinking about what particular aspect of your cartooning you want to improve the most and then seek out someone "who does this well, so you can absorb as much information as possible."

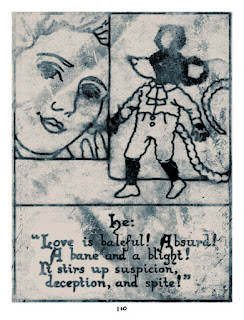

Alexis Frederick-Frost, a 2007 graduate (and later a faculty member), worked with Jason Lutes, an artist whose work he admired. He didn't get everything he wanted out of the experience, but said "I think my hopes were unreasonable." He felt that Lutes believed that “a developing cartoonist must work out a method that works for themselves. This process of discovering a cartooning ethic relies heavily on the individual artists' intuition to determine what feels right.” As a result, it was difficult to get tough criticism or "concrete changes to a process that is unique to each individual". Like Piersol and Bonesteel, he advised against picking a favorite artist as an advisor, instead suggesting choosing "a good comics editor or critic", someone who "can articulate if the work is effective and where it lacks clarity."

The Advisor As Intuitive Guide

Each artist is different, of course, and some advisors simply possess not just a higher level of dedication than others, but also a different feel for how the process should go and how to interact with their students. Consider the examples of 2010 graduates Jose-Luis Olivares and Jason Week. Olivares chose Dylan Horrocks as his advisor, in large part because he admired his work and the variety of ways in which he's published. In particular, Olivares could sense that Horrocks was an intuitive storyteller, something that he shared with him. Unlike Frederick-Frost's example, where two intuitive storytellers didn't mix, in this relationship, Horrocks explicitly stated that he didn't want to impose his own approach on Olivares, instead wanting to help him "develop [his] own voice and methods." While he saw that Olivares was "exploding with stories and talent", he felt he "needed the confidence" to follow his feelings about making comics. Olivares confirmed this, saying that Horrocks made him "feel comfortable following my own intuition", engaging in a "slow process of trusting myself." It was easy for him to trust Horrocks' opinion because he admired him so much, and while this approach hasn't worked out for everyone, he was fortunate that Horrocks was able to give him exactly what he needed as an artist.

The same was true for Jason Week, who chose Evan Dorkin as his advisor. He had been a long-time admirer of Dorkin's work and knew that, like himself, Dorkin had been self-taught. He also noted that they might have similar temperaments and was especially moved by Dork #7, a comic that documented Dorkin's nervous breakdown. "It was enormous to me to see that someone out there was managing similar problems to my own while still pushing his creative life forward." Week took an important step in the student-advisor relationship when he told Dorkin to be absolutely brutal in evaluating his work. He received that critique, but was also excited to find that Dork was "totally honest without being bullying or negative, and being a very incisive critic...nearly every bit of advice or criticism he gave me was something specific I could work on to become a better cartoonist." Dorkin went the extra mile in terms of "panel-by-panel breakdowns of specific strips" and at one point "even wrote out a ten page word doc that went through six strips in a row." It was through this process that Week came to understand how much of an influence Dorkin had been on his style, and his advice enabled him to "better direct the cluttered imagery I use, to better individualize the voices of my characters, and to be constantly using background action to build character and push plot forward."

For his part, Dorkin was nervous about diving into this role because he had no previous experience as an instructor. "I didn't attend art school and my critical thinking is more of a from-the-gut sort of thing...I don't feel like an 'expert' at anything in regards to making comics", he explained. That said, he was intrigued by the "test" of trying to "help someone out and get results". Dorkin had no such mentor when he was a younger cartoonist and he felt it "cost me years of development". That's a running theme of CCS itself: the belief that someone can become a working cartoonist in just a couple of years if they are properly motivated and have the right training and support. Dorkin was gratified to see Week's progress, both in terms of effort and "solidifying his style & approach and thinking more aggressively about what he's doing, what he wants and how to get it on the page."

The Educator As Advisor

Tom Hart was named by many as a favorite advisor. For his part, the SVA professor said that "I am always thrilled to be a mentor. I am mostly self-taught, and with the exception for some excellent friendships and peer relationships, I didn't have the active mentoring, yet I believe in its efficacy very much." 2010 graduate Melissa Mendes chose him because she initially was interested in teaching, but even when she changed course she valued their relationship because "we share a lot of opinions about creativity and learning" and "whatever my thesis project ended up being about, having an experienced teacher as an advisor would be really helpful." While Mendes chose a more traditional type of advisor, her actual choice was based on feel and a sense of creative compatibility.

She also said that Hart, "because he has so much experience teaching, is probably really conscious about influencing his students. I mean [this] in the sense that as a teacher you don't want to change the way your students draw, you want to make suggestions to them and help them figure out how they draw. " This was true of every advisor I received feedback about or from: no one was trying to make someone draw like them, and instead went out of their way to focus on the student's needs and skill sets. Hart added "Learning to read each student is an important skill, but it often comes down to understanding what they want to do/say, having some insight on how to improve, deepen that, and offering advice where I can. Then, being a very close careful reader and advising on the technical aspects as well." In this particular case, Mendes was deeply impressed that "Tom's style is so free and loose and organic feeling, and then there is soooo much thought and consideration behind it", allowing her to feel comfortable balancing spontaneity and planning. Hart said his greatest reward is having "helped someone articulate themselves better. It's always about communication, and being heard." He would likely be pleased to hear that Mendes considers him to be her "advisor for life".

White River Junction's Power Couple

Katherine Roy and Tim Stout are unusual in a number of different ways as recent graduates of CCS. They were the first husband-and-wife artist duo to be admitted to the school, for starters. Judging from their responses to my inquiry, they were also two of the most self-motivated and focused artists to come from CCS, which was also reflected in their interesting choices for advisor. Roy chose illustrator and author David Macaulay, her junior year advisor at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Roy's background was in illustration and writing, and going to CCS was a way of combining these two skills. Picking up on the themes cited by past graduates, she chose someone that she trusted and worked well with, rather than a star in the world of comics.

Macaulay is not a cartoonist, but offered "a fresh pair of eyes for my work. If he didn't get it, then I needed to redo it. End of story." At the same time, his skill as an illustrator helped her when stuck composing a page; she credits improvement as an artist to being acutely aware of her own weaknesses and choosing an advisor strong in those areas to help her through tough spots. Despite his aid, Roy was occasionally frustrated "that he couldn't tell me what the right answer was, in spite of his experience. That no one can tell you what the right answer is: it's something you have to figure out for yourself. And it can feel like the hardest thing in the world."

Tim Stout, on the other hand, faced a different problem. "During my first year at CCS, I found I had more skills in writing and editing than in drawing." The enterprising Stout started a "consultation service for comics storytelling called Coffee-4-Crit" and realized that his future lay in editing and writing. As such, he wanted an advisor who was comfortable in both roles, along with the business aspect of comics, and so he chose former Kitchen Sink publisher Denis Kitchen. His influence on Stout would wind up being different than the usual advisor presence; Stout said Kitchen "had more of an impact on the business materials I sent him [than on his comics]. His savvy business sense has helped me in the design of my business card, letterhead, envelopes, cover letters, resumes, etc. Even though we are entering the art field as 'artists' we will have to be business people to make a living, so it's best to be prepared for that." That's right in line with one of the stated goals of the school, that each student should be learning lessons that will keep cartooning as a central focus in their lives. CCS, by its nature, is not for dilettantes.

On a different note, when asked what he might have done differently, Stout said that he regretted attempting to write an entire graphic novel as his thesis project, because "Denis had difficulty giving big-picture critiques on a work in progress and by the time I would receive feedback from him about little changes, I had already received similar comments from the faculty or my peers. In hindsight, if I had wanted to fully utilize the relationship I had with Denis during my thesis year, I would have focused on short pieces and I would have worked on multiple shorts at a time, [so that] while waiting for critiques on one project, I'd write the rough draft for another." The fact that virtually every advisor was far from Vermont certainly had an impact, and Stout felt like doing those shorter pieces would have made more sense. CCS grad J.P. Coovert agreed, saying "If you decide to do a graphic novel, don't expect to finish it. Maybe try doing some smaller stories too and just writing/thumbnailing your book." Advisor Jesse Reklaw summed it up by saying "Young cartoonists always want to make a graphic novel or a monthly comic series, even though everyone encourages them to start small with 6-10 page short stories. I guess some things have to be learned the hard way."

Conclusion: The Hard Work Of Community

The underlying themes I detected from the feedback of students and advisors alike were the notions of community, continuity between generations and the need to reach out to other cartoonists. A number of advisors indicated that they were eager to take the position because they admired what the school was doing and had been following the output of its students. Others talked about their own journeys as young cartoonists as motivation. In the case of Jeffrey Brown, he felt that "I've been extremely fortunate to have an older generation of cartoonists who have mentored me in various ways to various extents, and I think it's good to pass that on. I also think that there's a lot one can learn from trying to help someone else understand their work, things which can then help one see their own work in new ways." Jesse Reklaw also indicated that he wanted "to give back to the comics community through advising, pedagogy, and general support", but also said that the fact he was self-taught motivated him to want to help young cartoonists. A number of advisors indicated that they were intrigued by this role because they had given some thought to teaching on a more formal basis, and being an advisor gave them the opportunity for a one-on-one dry run.

The nature of the community created at CCS, for both student-student and student-advisor relationships, is not one of unconditional praise. "Team Comics" this isn't. Students at CCS not only quickly learn to develop a thick skin, many are even eager to receive the most brutally honest critiques possible. Indeed, as a critic who's focused a lot of attention on CCS student work, I've been amazed to see that thick skin in action. CCS students are grateful for in-depth feedback, even (and frequently especially) when it focuses on weaknesses and mistakes. The community that CCS fosters demands hard work and values a relentless commitment to improvement. The time and money invested by each student in the experience lends itself to attracting only the most motivated of students, an advantage that is instrumental in fostering this culture of constantly striving to get better.

In many respects, the thesis year is an opportunity for students to not only demonstrate what they've learned, but to also reveal how far they have to go. It's a dry run for the process of becoming a professional cartoonist, or at least one who makes comics one of the top priorities in their lives. This is the chance for a young artist to figure out what they're trying to do as a creator. Roy said "I want to make work for anyone who wants to read it, and I try to consider the clarity, accessibility, and audience at all times. To think of my reader, but not for my reader." It's a chance for a young cartoonist to see their work through the eyes of a professional. However, as Stout warns, "Your advisor is not meant to be an all-knowing vending machine of comics wisdom. They are meant to be a professional contact. Build a relationship with them. They want to help, so make it easy: learn their strengths, ask questions directed to those strengths, and be ready for feedback."

Most of all, it's an opportunity for the student to carefully decide how to best utilize an available resource so as to get better. As Terry said, "I figure that choosing an advisor is hit or miss. They might not be helpful, and even if you get someone really great, life happens and that person may not be able to spend as much time tutoring as they thought. If you get a dedicated advisor, then don't be afraid to take the bull by horns. Set the schedule and the tone for the relationship. You've got to let them know what you want, otherwise how the hell are you going to get it?" That attitude fits right in with Sturm's vision for the process: "The advisors are incredibly important to CCS's program, but all the hard work still has to be done by the student. The student's individual grit is by far the most important element of their education."

The author wishes to thank the time the students and faculty of CCS took to answer his many questions, especially during thesis review period. Special thanks go to Robyn Chapman, who went above and beyond to answer any and every query presented to her.

Cartoonists Leading Cartoonists: The Trials and Rewards of Getting Mentored By The Likes of Alison Bechdel, Jeff Smith, Stan Sakai, R. Sikoryal, Jesse Reklaw, Denis Kitchen, Tom Hart, Dylan Horrocks David Macaulay and Evan Dorkin, by Robert Clough.

Matt Aucoin was always anxious to hear back from his senior thesis advisor, Stan Sakai, because "I would wonder how bad I messed up each time. But that's the same with every critique. Stan was always so polite when he gave a critique, that it was never disheartening. Stan was also very patient with me." At the Center for Cartoon Studies, the nature of each student-mentor interaction is different for each artist, but it seems that nearly every artist wants the unvarnished truth. "He asked me flat out, 'How much feedback do you want me to give you on your work?' I told him, 'I want it all, everything you've got.' Stan let out a long sigh and then jumped into all the holes I had with [my comic] Die, Baby, Die! He understood what I was going for, but I had sorely missed the mark on my first draft. He added a few scenes and told me how he would tell that story."

Having a mentor is a rare opportunity for young cartoonists to hone technical aspects of their craft that they might not have had the opportunity to either develop on their own or in a larger classroom setting. "I felt that Stan's strong points were my weak points as a cartoonist, and I wanted to work on those as much as I could in my senior year. Stan's great at lettering, storytelling, page layout, composition, perspective and pacing. I wanted to be great at those things too." Going into specifics, Aucoin said, "He would tell me the panels that worked and let me know of the ones that didn't. He would even go so far as to print out my pages, draw all over them, and send them back to me. This was a real treat, getting to see Stan draw my characters in his style. At first, I didn't want to redraw the panels and told him so. After thinking about it, I realized that he was right and ended up redrawing every panel he suggested. Stan was the kind of advisor who told me everything I did wrong, but in such a gentle manner that I never felt put out. After getting feedback from him, I was ready and excited to go back to the drawing board."

Interviewing nearly two dozen graduates of CCS, I discovered the quality of the student-advisor relationship tended to vary widely. Sometimes a negative experience was the fault of an advisor was wasn't prepaed to commit the sort of time and effort that a motivated student would need. Sometimes students were inadequately organized and didn't follow through on their commitments. On other occasions, students and advisors simply weren't appropriate matches on an aesthetic and sometimes personal level. Every graduate had different advice for future students on how best to make this relationship work, but Aucoin hit the nail on the head when he said, "The ball is mostly in the student's court. If you can't produce work for your advisor to critique, they can't critique your work. If you don't tell them what kind of feedback you want an need, they might not give it to you."

Creating Cartoon College

Teaching cartooning at a university level is not a new idea. Indeed, the School of Visual Arts was co-founded by legendary cartoonist Burne Hogarth. There are a handful of other institutions where one can learn how to become a cartoonist, like the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD) and the Minneapolis College of Art & Design (MCAD). Those schools offer cartooning and illustration programs as individual majors that are part of a more diverse curriculum. Then there's the Kubert School Of Cartoon & Graphic Art, a trade school that seeks to train the next generation of genre artists.

The expanded curricula from these schools has been a response to the rising demand by young cartoonists for formal education. Whereas art schools used to sneer at comics as an art form (one is reminded of Daniel Clowes' classic short story "Art School Confidential"), such pedagogy has now become much more widely accepted. The fact that such highly regarded cartoonists as Gary Panter, Zak Sally, David Mazzucchelli, and Carol Tyler are faculty members at various art schools and universities is a testament to how seriously those institutions have responded to this demand. That said, the cartooning programs at these schools are a small part of those institutions' overall scope. To a certain degree, the schools had to adjust to the demand by expanding programs, rather than building a cartooning program from the ground up. There wasn't an art school whose sole focus was on comics--not animation, not illustration--until quite recently.

In 2005, cartoonist James Sturm and designer Michelle Ollie founded the Center for Cartoon Studies in the small town of White River Junction, Vermont. Sturm had been a professor at SCAD and Ollie at MCAD, and they pooled their collective experiences to create a vision of a pedagogy for comics that sought to provide training and guidance for young cartoonists, pushing them to put theory into practice right away. What at first appeared to be a quixotic notion has now blossomed into a successful enterprise, thanks to the generosity of state and local governments and the kindness (& resources) of dozens of important figures from the world of comics. (Full disclosure: TCJ publisher Gary Groth is a member of the school's advisory board.) Indeed, what sustained CCS through its earliest months was a sound business plan that attracted investors. A look at its board of directors includes publishers, local businesspeople, non-profit experts and academicians. After years of experience as educators, it was obvious that Ollie & Sturm put a great deal of thought into this endeavor.

While the school is not accredited (a drawback that prevents them from being able to offer federal loans to students), it has been granted the ability to offer MFAs. This has no doubt helped them in getting more prospective students to apply, given the promise of a degree that might help them earn future positions in academia. Wisely, Ollie & Sturm decided to open CCS up to those who did not have college degrees, allowing for a more diverse student population. Those accepted for the two-year MFA program were welcome with a degree in any academic discipline; no previous training in art was required or expected. From the very beginning, Sturm made it clear that he viewed cartooning, storytelling and drawing as distinctly separate but related skills. That's certainly reflected in the first-year courses, which all students are required to take. It was also clear that he thought all three could be taught to highly-motivated students.

The initial founding of the school drew mixed reactions in the world of comics. Some observers sneered at the idea of paying $30,000 to learn how to make minicomics. A few veteran artists scoffed at the notion of formal education being needed to learn how to become a cartoonist. So many members of the underground and early alt-comics generations were self-taught that they viewed this as the best way to learn the craft. They possessed a sense of the artist as rugged individualist, making comics solely to please themselves. The idea of submitting to someone else's idea of what making a comic should be and being judged on it at a formal level was perhaps anathema to them. At a deeper level, this critique of CCS is more about comics as a manifestation of the cultural zeitgeist than it is about actually learning how to become a cartoonist. For many artists of the underground era, comics were their way of expressing themselves within the greater counter-cultural framework. For the generation that came to prominence in the early 80s, many saw comics as an extension of the DIY punk rock ethic, with the Hernandez brothers being the most prominent example. I would contend that it wasn't until what I refer to as the Xeric generation of artists in the 1990s that the idea of outside guidance and assistance became an acceptable part of the culture, a concept that became further entrenched with the rise of alt-comics conventions like APE and SPX in the late 90s.

While those conventions have a distinctive DIY flavor to them, they've also spawned a new generation of cartoonists eager to be inspired by their peers as well as their elders. What's interesting about CCS is that it's captured the intimacy and community of these convention experiences and has fused it with an intense, demanding curriculum where one is pushed by one's peers as much as one's teachers. In detailing the difference between CCS and other art schools, faculty member Robyn Chapman said "Probably the most significant difference is size. We only accept 24 students each year. That class of 24 is a very tight community. They all take the same classes, together, for 2 years. Outside of the classroom, they spend a lot of time together drawing, and also watching movies, playing board games, partying, even playing sports - all the normal social activities of college students. But with a lot more drawing."

"As a community, they learn a lot from each other, and they push each other to do their strongest work. The community here is key. I went to SCAD, at that point I think there were a few hundred students in the Sequential Art program. Most of them I never knew, and the few I knew, I didn't know very well. Here, you know all your classmates pretty intimately. [Fellow faculty member] Steve Bissette has used the word "tribe" to describe the unique community here. I think it's apt."

The CCS Curriculum and The Thesis Advisor

The first year curriculum has been described by Sturm as a "cartoonist boot camp". Each student takes a drawing class (with a life drawing session), a history of comics survey, a cartooning class, a writing workshop and also participates in visiting-artist seminars. Those have ranged from genre artists to children's book illustrators to minicomics stalwarts to the cream of the alt-comics set. While drawing is obviously crucial in this program, there's an understanding that cartooning itself is a kind of writing and can't be reduced to simple draftsmanship. While this approach is not unique, what is unusual is their early focus on design and publication. Chapman notes, "CCS understands that comics is a publishing art. This may sound basic, but this point is missing from some cartooning programs. Some cartooning programs tend to dissect the medium into its more superficial aspects and focus on methods and techniques. CCS is focused on telling stories and making books. From day one, our students are self-publishing."

The second year at CCS, for those who choose to take it, is as loose as the first year is regimented. The thesis project, to quote materials from the school, is "at the heart of CCS's second year curriculum" and "should reflect two semesters' worth of exploration, culminating in a well-constructed final project." That project is evaluated on the content itself, presentation and the work in context with the amount of time spent on it. The thesis determines a passing or failing grade and so carries with it an enormous amount of pressure, although this is to be expected at any kind of graduate program. During the year, each student meets regularly with both faculty and peers to evaluate works-in-progress in an effort to keep everyone on track. The tight-knit nature of this community, further aided by the lack of distractions in the tiny railroad town of White River Junction, means that no one is forgotten. In addition to these measures, each student is expected to pick a thesis advisor, usually from outside of the school.

As Sturm notes, it is hoped that the advisor will help the student with "the nuts and bolts of their cartooning" but also add "insight as to what it takes to make cartooning the center of their life going forward." Michelle Ollie described their role as offering "the benefit of another outside perspective, a point of feedback, extending beyond the interaction with the core faculty of the program and peers." I communicated with two dozen graduates and a handful of advisors about this experience and what it meant to them. That relationship, in many ways, reflected the nature of the thesis process itself, because it forced students to create their own schedules and deadlines and learn how to work with other professionals. Sturm said "The advisors aren't responsible for whip cracking or grading or anything like that. The onus is on the student to produce work for the advisor to respond to. Every advisor/student relationship is different. [For] some it's a week-to-week engagement, for others it's once or twice a semester. All depends on what makes the most sense to the individual personalities involved."

While Sturm said that the feedback for this process has been "mostly positive", he did note that "sometimes advisors drop the ball; they get too busy with deadlines or on tour or just don't make the proper time for whatever reason." Given that this is a paid position (a prospect that advisors Jesse Reklaw & Evan Dorkin both noted was a significant inducement), there's a risk involved in investing in services that may well not pan out for the students. Chapman notes that CCS understands this possibility and plans around it: "The nature of the thesis advisor relationship depends on the dedication of both parties, the student and the advisor. Sometime that dedication is not adequate – both students and advisors have been guilty of this in the past. That is a reason that advisors are only required to commit to one semester. If the relationship is not working, they can choose to end it after one semester. The same goes for students - if they are not satisfied with their advisor, they can select a new one after one semester."

The Perils of The Advising Process

One thing that became clear in the course of these communications is that picking an advisor was more of an art than a science. For every glowing description of how much their advisor helped them, I also heard stories about advisors who were impossible to track down. Some students had radically different experiences with the same advisor. For example, CCS graduates Sean Ford and Laura Terry both had Alison Bechdel as their advisor in different years. Terry was absolutely effusive in her praise for Bechdel and her commitment. After an initial face-to-face meeting (a rarity in this process), Terry set up a "rigorous schedule" with Bechdel, sending a package with her work-to-date on a weekly basis during the first semester. Terry said "Every two weeks we phoned or Skyped and there were occasional emails between us. Her criticism was always apt, and she let me know what was working, what wasn't working, and always guided me towards the right path, but was never didactic."

On the other hand, when Ford chose Bechdel a couple of years earlier, he found that "she was incredibly busy with Fun Home and working on her next book for Houghton Mifflin and didn't have a ton of time to respond to emails." When asked what advice he might give to future students about the process, he concluded it by saying "Don't pick someone who had a book just come out that's forcing them to do book tours. Seriously." Fellow graduate Colleen Frakes echoed this, as both of the advisors she selected wound up going on book tours during her senior year. She still got a good bit out of her brief contacts, as Jeff Smith advised her to "Figure out how the story is going to end before you start it", noting, "You look smarter that way." The input from her second advisor led her to scrap her initial thesis idea. Given that her eventual thesis project led to a Xeric grant, that was sage advice indeed.

While the needs of each student and the styles of each advisor differed, a few trends emerged in the responses I received. Choosing one of your personal heroes as an advisor wasn't always a good idea. Some of them simply didn't have the skills or temperament to excel as an advisor in some cases, while in other examples the student was too starstruck to establish a real working relationship. One graduate who preferred to remain nameless chose a well-regarded underground legend as their advisor and found that their styles and personalities clashed to the extent where nothing was gained from the relationship. Sturm said that he tries to "steer students away from some cartoonists, who despite their wonderful work, may not make such great advisors. I also make thesis advisor suggestions even if the student is not necessarily familiar with the work of that artist." The most-praised advisors tended to be those that either had experience as educators (like Tom Hart) or editors (like R.Sikoryak).

In the case of 2009 CCS graduate Jeremiah Piersol, he had "a lot of difficulty choosing an advisor", wanting someone who would "understand my point of view, and wouldn't push me in a direction of making my work more refined, commercial, etc". Sturm recommended Sikoryak, and Piersol said "His suggestion turned out to be golden." Piersol made an interesting distinction in relating his experience, saying the process "shouldn't work as an apprentice or mentorship situation like it did, for example, with the old masters of the Renaissance." Instead, Sikoryak guided him in "observing and understanding my own work in new ways that I may not have figured out on my own." In technical terms, he found Sikoryak's understanding of cartooning to be especially valuable, particularly "an emphasis on consistency. Sometimes the same character would look different panel to panel in my work, and with his feedback I recognized this." He emphasized that "having R.Sikoryak as an advisor also made me a hell of a lot less lazy as a cartoonist."

2010 graduate G.P. Bonesteel had a similar experience with Sikoryak, taking him as an advisor at Sturm's suggestion after his first advisor didn't work out for him. Sikoryak zeroed in on his character relationships, noting that they talked to the "camera" instead of each other. Bonesteel said that the reason he did this "was one part laziness and two parts lack of confidence in my own abilities" but this comment "really stuck with me because it's true and will make my work stronger". Both he and Piersol urged fellow students not to pick someone famous because "you love their work and want to meet them" or "attach yourself to someone with a big name, because they have a big name". Piersol further urged them to "go in with a direction", thinking about what particular aspect of your cartooning you want to improve the most and then seek out someone "who does this well, so you can absorb as much information as possible."

Alexis Frederick-Frost, a 2007 graduate (and later a faculty member), worked with Jason Lutes, an artist whose work he admired. He didn't get everything he wanted out of the experience, but said "I think my hopes were unreasonable." He felt that Lutes believed that “a developing cartoonist must work out a method that works for themselves. This process of discovering a cartooning ethic relies heavily on the individual artists' intuition to determine what feels right.” As a result, it was difficult to get tough criticism or "concrete changes to a process that is unique to each individual". Like Piersol and Bonesteel, he advised against picking a favorite artist as an advisor, instead suggesting choosing "a good comics editor or critic", someone who "can articulate if the work is effective and where it lacks clarity."

The Advisor As Intuitive Guide

Each artist is different, of course, and some advisors simply possess not just a higher level of dedication than others, but also a different feel for how the process should go and how to interact with their students. Consider the examples of 2010 graduates Jose-Luis Olivares and Jason Week. Olivares chose Dylan Horrocks as his advisor, in large part because he admired his work and the variety of ways in which he's published. In particular, Olivares could sense that Horrocks was an intuitive storyteller, something that he shared with him. Unlike Frederick-Frost's example, where two intuitive storytellers didn't mix, in this relationship, Horrocks explicitly stated that he didn't want to impose his own approach on Olivares, instead wanting to help him "develop [his] own voice and methods." While he saw that Olivares was "exploding with stories and talent", he felt he "needed the confidence" to follow his feelings about making comics. Olivares confirmed this, saying that Horrocks made him "feel comfortable following my own intuition", engaging in a "slow process of trusting myself." It was easy for him to trust Horrocks' opinion because he admired him so much, and while this approach hasn't worked out for everyone, he was fortunate that Horrocks was able to give him exactly what he needed as an artist.

The same was true for Jason Week, who chose Evan Dorkin as his advisor. He had been a long-time admirer of Dorkin's work and knew that, like himself, Dorkin had been self-taught. He also noted that they might have similar temperaments and was especially moved by Dork #7, a comic that documented Dorkin's nervous breakdown. "It was enormous to me to see that someone out there was managing similar problems to my own while still pushing his creative life forward." Week took an important step in the student-advisor relationship when he told Dorkin to be absolutely brutal in evaluating his work. He received that critique, but was also excited to find that Dork was "totally honest without being bullying or negative, and being a very incisive critic...nearly every bit of advice or criticism he gave me was something specific I could work on to become a better cartoonist." Dorkin went the extra mile in terms of "panel-by-panel breakdowns of specific strips" and at one point "even wrote out a ten page word doc that went through six strips in a row." It was through this process that Week came to understand how much of an influence Dorkin had been on his style, and his advice enabled him to "better direct the cluttered imagery I use, to better individualize the voices of my characters, and to be constantly using background action to build character and push plot forward."

For his part, Dorkin was nervous about diving into this role because he had no previous experience as an instructor. "I didn't attend art school and my critical thinking is more of a from-the-gut sort of thing...I don't feel like an 'expert' at anything in regards to making comics", he explained. That said, he was intrigued by the "test" of trying to "help someone out and get results". Dorkin had no such mentor when he was a younger cartoonist and he felt it "cost me years of development". That's a running theme of CCS itself: the belief that someone can become a working cartoonist in just a couple of years if they are properly motivated and have the right training and support. Dorkin was gratified to see Week's progress, both in terms of effort and "solidifying his style & approach and thinking more aggressively about what he's doing, what he wants and how to get it on the page."

The Educator As Advisor

Tom Hart was named by many as a favorite advisor. For his part, the SVA professor said that "I am always thrilled to be a mentor. I am mostly self-taught, and with the exception for some excellent friendships and peer relationships, I didn't have the active mentoring, yet I believe in its efficacy very much." 2010 graduate Melissa Mendes chose him because she initially was interested in teaching, but even when she changed course she valued their relationship because "we share a lot of opinions about creativity and learning" and "whatever my thesis project ended up being about, having an experienced teacher as an advisor would be really helpful." While Mendes chose a more traditional type of advisor, her actual choice was based on feel and a sense of creative compatibility.

She also said that Hart, "because he has so much experience teaching, is probably really conscious about influencing his students. I mean [this] in the sense that as a teacher you don't want to change the way your students draw, you want to make suggestions to them and help them figure out how they draw. " This was true of every advisor I received feedback about or from: no one was trying to make someone draw like them, and instead went out of their way to focus on the student's needs and skill sets. Hart added "Learning to read each student is an important skill, but it often comes down to understanding what they want to do/say, having some insight on how to improve, deepen that, and offering advice where I can. Then, being a very close careful reader and advising on the technical aspects as well." In this particular case, Mendes was deeply impressed that "Tom's style is so free and loose and organic feeling, and then there is soooo much thought and consideration behind it", allowing her to feel comfortable balancing spontaneity and planning. Hart said his greatest reward is having "helped someone articulate themselves better. It's always about communication, and being heard." He would likely be pleased to hear that Mendes considers him to be her "advisor for life".

White River Junction's Power Couple

Katherine Roy and Tim Stout are unusual in a number of different ways as recent graduates of CCS. They were the first husband-and-wife artist duo to be admitted to the school, for starters. Judging from their responses to my inquiry, they were also two of the most self-motivated and focused artists to come from CCS, which was also reflected in their interesting choices for advisor. Roy chose illustrator and author David Macaulay, her junior year advisor at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Roy's background was in illustration and writing, and going to CCS was a way of combining these two skills. Picking up on the themes cited by past graduates, she chose someone that she trusted and worked well with, rather than a star in the world of comics.

Macaulay is not a cartoonist, but offered "a fresh pair of eyes for my work. If he didn't get it, then I needed to redo it. End of story." At the same time, his skill as an illustrator helped her when stuck composing a page; she credits improvement as an artist to being acutely aware of her own weaknesses and choosing an advisor strong in those areas to help her through tough spots. Despite his aid, Roy was occasionally frustrated "that he couldn't tell me what the right answer was, in spite of his experience. That no one can tell you what the right answer is: it's something you have to figure out for yourself. And it can feel like the hardest thing in the world."

Tim Stout, on the other hand, faced a different problem. "During my first year at CCS, I found I had more skills in writing and editing than in drawing." The enterprising Stout started a "consultation service for comics storytelling called Coffee-4-Crit" and realized that his future lay in editing and writing. As such, he wanted an advisor who was comfortable in both roles, along with the business aspect of comics, and so he chose former Kitchen Sink publisher Denis Kitchen. His influence on Stout would wind up being different than the usual advisor presence; Stout said Kitchen "had more of an impact on the business materials I sent him [than on his comics]. His savvy business sense has helped me in the design of my business card, letterhead, envelopes, cover letters, resumes, etc. Even though we are entering the art field as 'artists' we will have to be business people to make a living, so it's best to be prepared for that." That's right in line with one of the stated goals of the school, that each student should be learning lessons that will keep cartooning as a central focus in their lives. CCS, by its nature, is not for dilettantes.

On a different note, when asked what he might have done differently, Stout said that he regretted attempting to write an entire graphic novel as his thesis project, because "Denis had difficulty giving big-picture critiques on a work in progress and by the time I would receive feedback from him about little changes, I had already received similar comments from the faculty or my peers. In hindsight, if I had wanted to fully utilize the relationship I had with Denis during my thesis year, I would have focused on short pieces and I would have worked on multiple shorts at a time, [so that] while waiting for critiques on one project, I'd write the rough draft for another." The fact that virtually every advisor was far from Vermont certainly had an impact, and Stout felt like doing those shorter pieces would have made more sense. CCS grad J.P. Coovert agreed, saying "If you decide to do a graphic novel, don't expect to finish it. Maybe try doing some smaller stories too and just writing/thumbnailing your book." Advisor Jesse Reklaw summed it up by saying "Young cartoonists always want to make a graphic novel or a monthly comic series, even though everyone encourages them to start small with 6-10 page short stories. I guess some things have to be learned the hard way."

Conclusion: The Hard Work Of Community

The underlying themes I detected from the feedback of students and advisors alike were the notions of community, continuity between generations and the need to reach out to other cartoonists. A number of advisors indicated that they were eager to take the position because they admired what the school was doing and had been following the output of its students. Others talked about their own journeys as young cartoonists as motivation. In the case of Jeffrey Brown, he felt that "I've been extremely fortunate to have an older generation of cartoonists who have mentored me in various ways to various extents, and I think it's good to pass that on. I also think that there's a lot one can learn from trying to help someone else understand their work, things which can then help one see their own work in new ways." Jesse Reklaw also indicated that he wanted "to give back to the comics community through advising, pedagogy, and general support", but also said that the fact he was self-taught motivated him to want to help young cartoonists. A number of advisors indicated that they were intrigued by this role because they had given some thought to teaching on a more formal basis, and being an advisor gave them the opportunity for a one-on-one dry run.

The nature of the community created at CCS, for both student-student and student-advisor relationships, is not one of unconditional praise. "Team Comics" this isn't. Students at CCS not only quickly learn to develop a thick skin, many are even eager to receive the most brutally honest critiques possible. Indeed, as a critic who's focused a lot of attention on CCS student work, I've been amazed to see that thick skin in action. CCS students are grateful for in-depth feedback, even (and frequently especially) when it focuses on weaknesses and mistakes. The community that CCS fosters demands hard work and values a relentless commitment to improvement. The time and money invested by each student in the experience lends itself to attracting only the most motivated of students, an advantage that is instrumental in fostering this culture of constantly striving to get better.

In many respects, the thesis year is an opportunity for students to not only demonstrate what they've learned, but to also reveal how far they have to go. It's a dry run for the process of becoming a professional cartoonist, or at least one who makes comics one of the top priorities in their lives. This is the chance for a young artist to figure out what they're trying to do as a creator. Roy said "I want to make work for anyone who wants to read it, and I try to consider the clarity, accessibility, and audience at all times. To think of my reader, but not for my reader." It's a chance for a young cartoonist to see their work through the eyes of a professional. However, as Stout warns, "Your advisor is not meant to be an all-knowing vending machine of comics wisdom. They are meant to be a professional contact. Build a relationship with them. They want to help, so make it easy: learn their strengths, ask questions directed to those strengths, and be ready for feedback."

Most of all, it's an opportunity for the student to carefully decide how to best utilize an available resource so as to get better. As Terry said, "I figure that choosing an advisor is hit or miss. They might not be helpful, and even if you get someone really great, life happens and that person may not be able to spend as much time tutoring as they thought. If you get a dedicated advisor, then don't be afraid to take the bull by horns. Set the schedule and the tone for the relationship. You've got to let them know what you want, otherwise how the hell are you going to get it?" That attitude fits right in with Sturm's vision for the process: "The advisors are incredibly important to CCS's program, but all the hard work still has to be done by the student. The student's individual grit is by far the most important element of their education."

The author wishes to thank the time the students and faculty of CCS took to answer his many questions, especially during thesis review period. Special thanks go to Robyn Chapman, who went above and beyond to answer any and every query presented to her.

Friday, December 4, 2015

Thirty Days of CCS #34: Dakota McFadzean

Dakota McFadzean's comics are among the best created by CCS alumni. He's got every technical tool to be a great cartoonist already. He can draw, convincingly and fluidly, in virtually any style. I'm not sure how much of that came from prior experience and how much of that came from CCS demanding that students learn to emulate different visual approaches in their assignments, but he's equally comfortable drawing in a naturalistic style, in a cartoony John Stanley/Irving Tripp pastiche, or in a sweaty, cluttered Evan Dorkin approximation. Beyond being technically accomplished as a draftsman, he has rock-solid storytelling chops. His panel-to-panel and page-to-page transitions are smooth and clever, though he rarely steps outside of standard grids and fairly conventional formal choices. He's not so much there to dazzle the reader as he is to tell a story and create an atmosphere.

There is a natural confluence of style, aesthetic influences and narrative choices in McFadzean's comics. His focus on loneliness, wide-open spaces and working class families most likely got its start from being raised in a small town in Saskatchewan. However, McFadzean often channels the supernatural, the grotesque and the inexplicable into his work as well. That pervasive sense of magical realism and dread sets his comics apart from most cartoonists. His frequently warm and inviting visual approach makes the eventual story twists all the more horrific.

His collection of daily strips, Don't Get Eaten By Anything, is a fascinating account of a young artist trying to get better in public by forcing himself to draw every day. Inspired by the patron saint of daily webcomics, James Kochalka, McFadzean began this strip as a typical 4-panel autobio strip but eventually abandoned that in favor of a more free-for exploration of his own dreams and nightmares. What McFadzean wound up creating was a one-man daily comics page where a number of recurring characters act as McFadzean's interchangeable avatars of dread. Moreover, his daily strip acted as an incubator for ideas that he would expand upon in his later short story.

One example is the Ghost Rabbit, a goofy character who was later used to darker effect in a mini of the same name. A strip about the existential quality of video games had its origins in a series of strips where one could practically feel the grime of a den and its greasy inhabitants. The sad, alienated and often angry characters found in McFadzean's regular work often started as inhabitants of a four-panel strip with a punchline. While the strips here stand on their own, the book offers the same sort of insight into McFadzean's creative process as a sketchbook might. In essence, the daily strip was his sketchbook.

McFadzean riffs a lot on pop culture, but not in the way one might think. When he refers to The Simpsons or Bugs Bunny, his drawings are monstrous and grotesque: childhood memories gone horribly astray. McFadzean has an uncanny sense of how to push the boundaries of good taste without going for the obvious gross-out gag, like in his "Invincible Baby" strips. These are exactly what the title suggests: an indestructible baby getting launched into space, shot, stabbed, absorbed by a black hole, etc and coming back no worse for the wear each time.

There are the tediously quotidian God Comics (whose tedium was entirely intentional), scribbled birds worrying about being snubbed, and monsters moping over their daily lives and their search for meaning. There's the old man with the thick, white moustache pondering his future. There's a man talking to an elephant, rarely getting the answers he wants. There are animals trying to escape their circumstances in strips that remind me a little of the sort of thing that Anders Nilsen does. There is also the occasionally happy interlude or image that results here, even though that obsessiveness factor eventually catches up with it. McFadzean even had a few multi-part stories in here that later got reworked.

Through it all, one can see certain arguments and approaches start to coalesce, as though problems he was working through on the page here got solved and translated into minis. For example, his comic Last Mountain 2 (Birdcage Bottom Books) contains elements that originally appeared in the daily strips, like the cartoony John Stanley/Irving Tripp art juxtaposed against disturbing events. In McFadzean's world, loners and outcasts aren't necessarily very nice people. They strike out at the world, alienating even those that approach them in a friendly manner. In that mini, in the story titled "Buzzy", a young kid starts at a new school, only to find that his off-putting and weird manner instantly draws all sorts of bullying and taunts. His response to such behavior is to go nuclear, moving to acts of extreme violence. Not everyone wants to be saved or is even capable of it. Some people are just doomed, in part by the way they react to the world. It's no accident that the figures are so cute and cartoony, because McFadzean set out to make the reader uncomfortable as old tropes and settings were explored from a different angle.

That sense of inevitable doom and dread is pervasive throughout the book, even as it's played for laughs in the gag strips. There are moments of bliss, but even beyond strips about sadness, fear, dread and devastation, the pervasive emotion felt throughout the book is simple disappointment. Whether it's a boy realizing that hitting someone doesn't feel as good as he thought it would to existential ennui even in the face of beauty, one can almost hear the sighs coming from this book. Still, the rabbit concentrates on not getting eaten, and another day goes by for the birds to achieve happiness or for the man with a walrus moustache to make human connections. McFadzean's worldview may be grim, but there's a survivalist streak there as well that puts aside nihilism in favor of braving the cold, bleak world.

There is a natural confluence of style, aesthetic influences and narrative choices in McFadzean's comics. His focus on loneliness, wide-open spaces and working class families most likely got its start from being raised in a small town in Saskatchewan. However, McFadzean often channels the supernatural, the grotesque and the inexplicable into his work as well. That pervasive sense of magical realism and dread sets his comics apart from most cartoonists. His frequently warm and inviting visual approach makes the eventual story twists all the more horrific.

His collection of daily strips, Don't Get Eaten By Anything, is a fascinating account of a young artist trying to get better in public by forcing himself to draw every day. Inspired by the patron saint of daily webcomics, James Kochalka, McFadzean began this strip as a typical 4-panel autobio strip but eventually abandoned that in favor of a more free-for exploration of his own dreams and nightmares. What McFadzean wound up creating was a one-man daily comics page where a number of recurring characters act as McFadzean's interchangeable avatars of dread. Moreover, his daily strip acted as an incubator for ideas that he would expand upon in his later short story.

One example is the Ghost Rabbit, a goofy character who was later used to darker effect in a mini of the same name. A strip about the existential quality of video games had its origins in a series of strips where one could practically feel the grime of a den and its greasy inhabitants. The sad, alienated and often angry characters found in McFadzean's regular work often started as inhabitants of a four-panel strip with a punchline. While the strips here stand on their own, the book offers the same sort of insight into McFadzean's creative process as a sketchbook might. In essence, the daily strip was his sketchbook.

McFadzean riffs a lot on pop culture, but not in the way one might think. When he refers to The Simpsons or Bugs Bunny, his drawings are monstrous and grotesque: childhood memories gone horribly astray. McFadzean has an uncanny sense of how to push the boundaries of good taste without going for the obvious gross-out gag, like in his "Invincible Baby" strips. These are exactly what the title suggests: an indestructible baby getting launched into space, shot, stabbed, absorbed by a black hole, etc and coming back no worse for the wear each time.

There are the tediously quotidian God Comics (whose tedium was entirely intentional), scribbled birds worrying about being snubbed, and monsters moping over their daily lives and their search for meaning. There's the old man with the thick, white moustache pondering his future. There's a man talking to an elephant, rarely getting the answers he wants. There are animals trying to escape their circumstances in strips that remind me a little of the sort of thing that Anders Nilsen does. There is also the occasionally happy interlude or image that results here, even though that obsessiveness factor eventually catches up with it. McFadzean even had a few multi-part stories in here that later got reworked.

Through it all, one can see certain arguments and approaches start to coalesce, as though problems he was working through on the page here got solved and translated into minis. For example, his comic Last Mountain 2 (Birdcage Bottom Books) contains elements that originally appeared in the daily strips, like the cartoony John Stanley/Irving Tripp art juxtaposed against disturbing events. In McFadzean's world, loners and outcasts aren't necessarily very nice people. They strike out at the world, alienating even those that approach them in a friendly manner. In that mini, in the story titled "Buzzy", a young kid starts at a new school, only to find that his off-putting and weird manner instantly draws all sorts of bullying and taunts. His response to such behavior is to go nuclear, moving to acts of extreme violence. Not everyone wants to be saved or is even capable of it. Some people are just doomed, in part by the way they react to the world. It's no accident that the figures are so cute and cartoony, because McFadzean set out to make the reader uncomfortable as old tropes and settings were explored from a different angle.

That sense of inevitable doom and dread is pervasive throughout the book, even as it's played for laughs in the gag strips. There are moments of bliss, but even beyond strips about sadness, fear, dread and devastation, the pervasive emotion felt throughout the book is simple disappointment. Whether it's a boy realizing that hitting someone doesn't feel as good as he thought it would to existential ennui even in the face of beauty, one can almost hear the sighs coming from this book. Still, the rabbit concentrates on not getting eaten, and another day goes by for the birds to achieve happiness or for the man with a walrus moustache to make human connections. McFadzean's worldview may be grim, but there's a survivalist streak there as well that puts aside nihilism in favor of braving the cold, bleak world.

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Thirty Days of CCS #33: Dog City