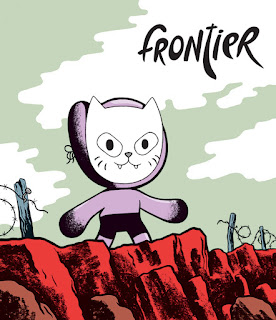

Of the newer alt-comics publishers, Youth In Decline's Ryan Sands reminds me the most of the late Dylan Williams of Sparkplug Comics. First, he has a particular aesthetic that guides his publishing choices above all other considerations. Second, he always has an eye on up-and-coming talent. Third, he not only is open to diversity in whom he publishes, it's clear that he seeks it out. In the first twelve issues of YID's anthology talent showcase, Frontier, Sands has published the work of eight women. Four issues have featured Americans, four issues have featured Canadians, and the rest have come from all over Europe. Some of the artists have submitted a single story for this mini-comic size publication (about 6.5 x 8"), while others have submitted several shorter stories. Some artists eschewed narratives altogether, preferring illustrations that have a sort of fractured narrative quality. All of them are in Sands' aesthetic wheelhouse, which can be described as an overlapping appreciation for what some might consider banal or limited genres like horror or erotica. Really, what Sands is most interested in is narratives and imagery about transformation, ritual, and identity. The approach each artist might use was less important than a certain bold willingness to take difficult and sometimes problematic ideas as far as they will go.

In Frontier #1 (2013), Russian artist Uno Moralez is featured. His character designs range from cartoony to naturalistic as they depict David Lynch-inspired torch singers, religious iconography as part of a visceral battle between good and evil, and scenes of voyeurism met with sheer, unrelenting horror. There's not a cohesive narrative connection between all of the images, but they have a thematic similarity in that Moralez is showing us a fallen world that's still met with pockets of desperate belief. For every moment of hope, there's an image of corruption, dissolution, and abject terror. What seems beautiful and desirable is destructive, and what is pure is eventually destroyed. The image of a boy with a telescope seeing a horrendous female demon with an almost prehensile tongue is especially terrifying, as she simply appears in front of him and chases him. We don't see her catch him, but we do see his head tilt at a sickening angle, with a demented grin spreading across is face. Many of the illustrations have a pixelated quality, as though Moralez wants the reader to understand the artificial nature of what they're seeing. That connection between image and reality is driven home at the end with a photo of Laura Dern ugly-crying in a scene from David Lynch's Wild At Heart, which is a film about a quest that slowly breaks down.

Frontier #2 (2013) features Hellen Jo in a comic filled with images of girl gangs in a sort of mythical California. Again, there's no particular story here other than imagining what might have led to the moments captured in time that Jo depicts, like one image of a group called the Bang Gang where one girl is putting on lipstick in a public bathroom while another is washing blood out of her mouth. Jo indicates in an afterword that these are fantasy figures based on girls she saw, feared and respected growing up, desiring the power and freedom they wielded. Jo's skill as an illustrator is remarkable, as she tells a lot of story with body language and the placement of figures in space. The details of what the girls are doing is less important than their poses and how they're doing it. Jo favors lavender and blue as her go-to colors for many of the illustrations, soft colors that both belies the toughness of the girls and underscores the fact that they are still young girls. Two girls who call themselves the Shit Twins stand against a wall with blank expressions, blue hair and fairly typical clothes--but one of them is wearing an eyepatch. There's another two page spread where a member of the Scalps is getting her hair buzzed while eating a lollipop and another is looking at art on a wall. Every illustration shares that weird tension between adulthood and childhood, one that Jo is careful not to sexualize in an exploitative manner. Indeed, the girls here are defiant and clearly do not give a fuck about anyone else's view of them. They have transformed from whatever they were before into something different, powerful and self-determining.

Frontier #3 (2014) includes three stories published in English for the first time by German artist Sascha Hommer. In an afterword, he says that his biggest influences are Chris Ware and Yuichi Yokoyama, and that's made clear by his simplified use of character design as well as an interest in oblique imagery. He uses a lot of zip-a-tone effects in "Drifter", which is essentially a shaggy-dog story about an escaped convict on what appears to be an alien planet. The story starts off with a jailer bitching about the convict's complaints about his room, and the story tensely follows his journey after escaping, only to reveal that he got what he really wanted in the end. In a story where every page was a nine-panel grid, Hommer always used the middle panel in the page not necessarily as a climax point, but as a tension point: his pursuers blown up, moving forward in a ridiculous disguise in a diner, wondering if the police would catch him, etc. "Transit" is about aliens investigating a small town in Austria for their mysterious purposes ("transit"--colonization?). Instead of simply following around a figure, the story has an almost clinical air about it, as we see computer screen images the aliens are following. The figures we do meet have a lumpy, almost bigfoot quality to them. "The Black Lord" is about a board game's main piece that we see over a long period of time, using that familiar Richard McGuire time-splintering effect that Ware has long favored. The ultimate fate of the figure is reflective of the game's theme of conquest and randomness. The latter two stories are all about transformation, while the first story is about the illusion of change.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment