This review was originally published at sequart.com in 2007.

*********************

The first English translation of Joann Sfar's that I read was The Rabbi's Cat. I was immediately struck by the pleasantly ambling plot, the expressive & loose art, and the lively way in which Sfar grappled with questions of faith, ethnicity and identity. Grounding the book in its titular narrator, a cat that gains (and later loses) the ability to speak, he displays an enormous amount of affection for his Jewish roots in North Africa while still engaging and gently chiding rhetoric for its own sake. With the cat, the Rabbi Abraham Sfar, his daughter and the truly inspired character of Malka of the Lions (the Rabbi's cousin), Sfar manipulates the plot to simply fall in place around the lives of these characters. The way Sfar can jump between lighthearted farce and adventure to weighty matters of philosophy (frequently on the same page) is aided by the vividness of his characters, with the cat acting as the ultimate cynic.

The new volume, featuring the stories "Heaven On Earth" and "Africa's Jerusalem", has a slightly more didactic feel to its stories. Sfar more explicitly grapples with issues relating to both anti-semitism and racism. In an author's note, it's clear that he was somewhat reluctant to go in this direction but eventually notes "Chances are everything's already been said, but since no one is paying attention you have to start all over again." Sfar makes both stories work because he successfully disguises his moral medicine in the form of funny but often rip-roaring adventure stories.

"Heaven On Earth" sees Malka, the con man/living legend, growing old with his trained lion. Malka is regarded more as a curiosity than an imposing figure who saves entire towns from his (on-demand) bloodthirsty lion, and he can't bear to live like that. So he ingeniously finds a way to create a mythology around his own death as yet another way of drumming up business. In the end, an act of political courage against an anti-semitic politician, done with no other motivation than anger and outrage, winds up really ensuring his legend. That neatly ties into the nature of political struggle and political identity, an issue that is still obviously quite a valuable one. The nature of Jewish identity, belief and behavior is at once strictly codified in ancient writings and subject to thousands of years of honest debate and shifty rhetoric. Still, the idea of a religion and an ethnicity that is constantly shifting and evolving based on the nature of this unfolding communal argument obviously fascinates Sfar. It's certainly led him to sympathize with any number of viewpoints, especially as Abraham is constantly battling with his own faith.

"Africa's Jerusalem" is the most complex "Rabbi's Cat" story to date. The whole story is one long debate of sorts about the ways different religions go about their practices, the nature of fanaticism, the possibility of ecumenical communication, the way race plays into all of these factors and much more. While Sfar hammers down on his overall message pretty hard, he creates a compelling narrative by growing the story organically from the way his characters interact and then crafting an adventure story that's a sly parody in many ways. The story begins with the rabbi's daughter having trouble with her new husband, himself a rabbi more obsessed with books than her own happiness. We then meet a Russian refugee escaping from a brutal pogrom shortly after the 1917 revolution who winds up by accident in Algeria, where the story is set. There's plenty of comedy mined out of his inability to communicate, including Rabbi Sfar's old teacher thinking the Russian is a golem.

The Rabbi finally looks up a priest who helps him find a local Russian, who is now an atheist. He helps translate for the young Russian immigrant, who happens to be a painter. It turns out he's looking for a legendary "black Jerusalem" in Ethiopia, with a lost tribe of "black Jews" where he hopes to be part of a new Israel. Abraham says that there's no such as a black Jew (saying it would be too much to bear for a single people to have had to endure pogroms and slavery), but the story appears to be true. So the Russians, Abraham, and the cat set out across Africa to try and find this city. They meet up with Abraham's cousin, a Muslim cleric, who joins their party.

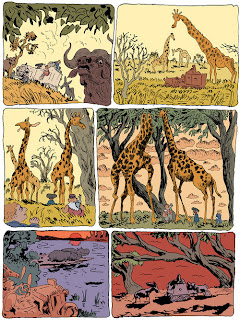

What follows is a series of adventures that's both in homage to and a parody of Tintin. The puckish explorer even makes a cameo as the ignorant and condescending explorer of "Tintin and the Congo", a scathing send-up of Herge. The party winds up in a Muslim prince's camp, where there's more than a little fanaticism and a clash of religious wills, along with a surprising death. The Russian artist meets a woman and Abraham marries them (after slightly bending the rules). During the arduous trip, most of the members of the party have to halt except for the happy couple. When they reach the city, the realize that not all is as its seems and everyone's perspective can get skewed if it's too closed off. The cat here is less cynical and nasty and more respectful and helpful, even getting his ability to speak back.

What saves the book from becoming a lecture is Sfar's essential light-heartedness. Even in the most harrowing of scenes, Sfar's faith in the possibilities that humanity possesses informs his worldview. Even the jaded cat can't help but be moved by the painter and many others he meets, while not afraid of meting out punishment to those that deserve it. He was the id to the Rabbi's super-ego when the series began, but it's obvious that both characters started to meet more in the middle with this story. Both have made to see that there was more to the world than could be accounted for in their point of view, and both started to understand the folly of dogmatism--either as a dogmatic holy man or dogmatic cynic. One can't help but love both of them, because they're the most complex characters in the book. Sfar is perhaps guilty of constructing a few too many one-dimensional straw men to rail against, which makes the points he's trying to emphasize a bit too obvious. However, by making the Rabbi and his cat so delightfully ambiguous and shifting in their points of view, having their worldviews threatened at every turn, he's able to mitigate the simplicity of the antagonists with the complexity of his protagonists.

That complexity and the affection he has for his characters is what draws me as a reader to them, again and again, and it's what makes Sfar such a fabulous storyteller. Sfar's figures are loose, expressive and at times rubbery. He uses a sketchy style that he will occasionally abandon to make a dramatic point of some kind, especially with the striking figure of Malka. He uses color to carry a lot of the storytelling load, giving the book a sumptuous feel. The iconic nature of most of his characters adds a touch of lightness to the visuals, never allowing it to bog down in eye-distracting ornamentation. While there are plenty of clever decorative touches, they all serve to draw the eye into his characterizations. There's a fluidity, grace and even whimsy to this book, adding to its breezy nature as a read but never quite allowing the reader to relinquish the responsibility of digesting Sfar's message.

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Amazing synchronicity. This is sitting in my amazon "cart" waiting to be purchased today.

ReplyDelete