This article was originally published at seqaurt.com in 2007.

**********

It's difficult as a critic to tackle Peanuts, because I was devouring these strips as soon as I could read. They're essential to the makeup of my comics-reading DNA and had an important influence on both my worldview and sense of humor. I had the fortune of gaining access to a number of reprints from the 50s and 60s as a young boy and so had an understanding at an early age that the tone and content of the strip shifted over time, since it was quite different than when I started reading the strip on a daily basis in the mid-1970s. Former Comics Journal critic Noah Berlatsky took artists like Chris Ware to task for emphasizing the melancholy nature of Peanuts rather than its wackier or more sentimental elements, but that criticism is shortsighted depending on what era of the strip one is reading. There's no question that the strip at its height (roughly from 1958-1967) is far more brutal and unsparing to its characters and far less sentimental and episodic than it would later become. That's due in part to some shifts in tone and focus on characters.

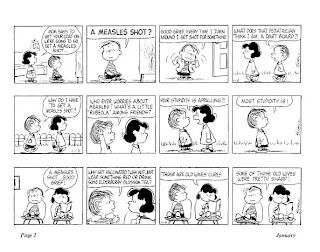

Snoopy shifts into serious fantasy-character mode here, as he appears on 32 separate pages as the World War I flying ace in the collection. Snoopy also pops up as a secret agent, an Olympic ice-skater and becomes a champion wrist-wrestler, as well as a piranha and a vulture. Schulz also seizes upon current events like measles shots (which Linus is in a panic about) and even touches on the burgeoning counter-culture. That's made explicit with the introduction of the long-haired "hippie-bird" that would later evolve into Woodstock, along with lines from Sally like "I hate your generation!". In addition to various characters protesting various things, Lucy also decides to hold a "crab-in". Schulz, unsolicited, decided to diversify his cast a bit with his first Hispanic character (Jose' Peterson, who never really went anywhere) and Franklin, the now well-known African-American character.

Charlie Brown has settled into dealing with more episodic threats to his existential well-being, with regular abuse at the hands of the kite-eating tree, yearly frustration with Valentine's Day and Lucy taking away the football, and free-floating angst with the little red-haired girl. My favorite strips always revolved around baseball, because this always pointed to Charlie Brown's greatness as a character. Despite the fact that he's a put-upon, wishy-washy nebbish, he always remains a sympathetic character because he's an active protagonist. Despite his unrelenting string of failures in pretty much everything, he never stops trying. Not only that, but with baseball in particular, he never loses his love for his pursuit and his hope that he might one day get better. There's one amazing strip from 3/15/1967 that doesn't actually have a punchline. His team has just lost their first game of the season, and Charlie Brown says, "Losing a ball game is like dropping an ice cream cone on the sidewalk...it just lays there and you know you've dropped it and there's nothing you can do...it's too late..." The last panel just has his head down, exclaiming "Rats!".

Despite everything, Charlie Brown remains a competitor, despite the fact that he's hopelessly outmatched. That deep feeling of rage is what makes him so compelling; if he was nothing but mere melancholy, he'd be insufferable. His anger at the world and his desire to change it despite all evidence to the contrary is why he's one of the greatest characters in the history of comics. There's a great sequence where Peppermint Patty offers Charlie Brown four of her own players for Snoopy and Charlie Brown accepts. He's then horrified at himself for trading away his own dog just for the sake of winning some baseball games and everyone else is even more horrified. It's the first time I can recall in this strip where Charlie Brown does the wrong thing morally and is called out on it, though he does do the right thing in the end.

The other major stars of this volume are Lucy, Linus, Sally and Peppermint Patty. Lucy engages in all of her usual crabby behavior, but her general viciousness is on full display here. She is pure, unstoppable id, frustrated only by Schroeder's total disinterest in her. Linus is both the most thoughtful character in the strip and the most ineffectual in some ways. He's more afraid of things than usual in this book: shots, being shunned by his teacher, vultures, piranha, etc. He's also the most intellectually adventurous character in the strip even though he struggles with his schoolwork. Sally is constantly confused and angry at her world, which offers a nice contrast with Lucy who demands that the world conform to her own understanding of it. Sally is baffled by everything and demands that everyone explain it to her, usually with hilarious results.

Peppermint Patty represents the biggest shift in tone for the strip. She's the first major new character in the strip to get whole weeks devoted to her and usually completely outside the purview of the regular Peanuts' gang neighborhood. It's almost like she's a character from an entirely different strip that just happens to regularly cross over with Peanuts. She's a misfit in her own way, but she's sort of Charlie Brown's mirror image: she's confident, feels loved and is never afraid to offer up her opinion. While she's a bit rough around the edges, she lacks Lucy's cruelty and Violet's cattiness. The sequence where she's the tent monitor for a group of younger girls was hilarious, and one could almost sense Schulz' excitement in doing a very different kind of story in his long-running strip, eighteen years into its production.

That's the stunning thing about this book. In over 700 strips, there are a number of long laughs to be had and very few clunkers. Schulz was always reluctant to reproduce his entire body of work (which led to the reprints and reprints of reprints with so many repeated strips) because of strips that he either thought were weak or didn't age well. In the context of a career overview such as this, I'm grateful that every strip is being reprinted, in chronological order. Seeing his line develop over time, seeing him come up with new ideas and character and which ones stuck and which ones didn't is fascinating to observe. There's also a certain delightful weight of history that builds as one goes from volume to volume. One wonders how much the intense, world-renowned fame of his strip affected him as an artist at this point. Did he feel the urge to bring back popular tropes based on reader feedback and demand, or did he ignore such concerns and simply draw what he wanted? It seems like with this volume he tried to do a little of both, keeping old fans happy while always trying to keep himself interested with new challenges.

In terms of the visuals, Schulz is years into his mature style. He's exactly what I mean when I talk about an artist needing to find the ideal style with which to express themselves with clarity. For Schulz, though his line is spare, it's full of life and liveliness. He's not afraid to stylize his drawings when need be, especially in the pursuit of action. His strip has a surprising energy and flow to it when he chooses to pursue that sort of story (usually involving Snoopy), creating an almost visceral crunch in these scenes. He's also a master of gesture, expression and the quiet moment. He leavens the frequently violent confrontations in his strip with heartfelt emotion, and is equally skilled at making his audience feel both.

This series of reprints is one of the most important in the history of comics, for so many reasons. It keeps alive the legacy of the comics artist who may have been the most important cartoonist of the latter half of the 20th century. It puts the now-ubiquitous Peanuts iconography back on comic book pages instead of simply being known through advertising and merchandising. And of course, the fact that Jeannie Schulz and the Schulz estate licensed this to Fantagraphics not only started off a new golden age of classic strip reprints, it's also funded numerous worthy publications from FBI. While those concerns are impressive, the mere fact that Fantagraphics has committed itself to this project, and that it's done so well (special kudos to Seth for design and John Waters for his very astute and engaged introduction) is a gift to fans of the art.

*********

This article was originally published at sequart.com in 2008.

In The Complete Peanuts 1969-70, it's interesting to see popular culture influence Schulz in a more direct way than before. He makes cracks about feminism and has Sally utter "I hate your generation!" to an older kid. Schulz is very much still at the height of his powers but was also looking for new ways to entertain himself while processing the world around him. The most prominent character in this volume is clearly Snoopy. Schulz assigned him a bird as a sidekick and pointedly named him Woodstock, devoting an entire strip to this revelation. It was an odd gag, as though making a reference to hippies was funny in and of itself. Most every long storyline in these years involved Snoopy: being sent before the Head Beagle (thanks to Frieda turning him in for not chasing rabbits), becoming the Head Beagle and then quitting, trying to help Woodstock fly south for the winter and getting lost, trying to find his mother, being asked to make a speech at the Daisy Hill Puppy Farm and getting caught up in an anti-war riot. The Head Beagle stuff is the strip at its weirdest, coming up with a sort of an overriding mythology that seeks to somehow connect Snoopy's behavior as a dog and his status as a sort of person. When it's revealed that Snoopy owns a piece of land that the city wants and he's unwilling to sell, he's resistant because he's not allowed to vote or run around without a leash.

That weird tension between animal and character is at play through this volume; Snoopy does things like go to the vet, goes to a kennel and is forced to stay with Lucy when Charlie Brown goes on vacation. He also spends a lot of time as the World War I flying ace, as a hockey pro (often against Woodstock), a novelist (the legendary "It was a dark and stormy night..." strips), astronaut and most oddly, a "world-famous grocery clerk". That particular set of strips almost seemed like a strange parody of the other Snoopy fantasy roles, with Snoopy even noting that there weren't more than a dozen famous grocery clerks. It's as though Schulz was fascinated by his local grocery clerk bellowing out questions at his market and had to channel this into his strip.

Peppermint Patty continued to draw a lot of focus in this volume, and much of it had a bittersweet quality. She was still confident and brash, but Schulz instilled her with all sorts of insecurities. Peppermint Patty despaired over not being beautiful, over not being able to wear sandals at school, and in general over her lack of femininity. Charlie Brown had no idea what to make of her or what to say to her, especially when she ran roughshod over him in conversations. At the same time, he was clearly pleased by her lack of pettiness and guile. About the only time Charlie Brown felt good in this volume was when he loaned a glove to a teammate of Peppermint Patty's and he wouldn't give it back. He felt good because the kid he took it resented Charlie Brown for "thinking he was better than him"--and this notion positively delighted him. Perhaps the sweetest segment in the book came when Peppermint Patty asked Snoopy (whom she didn't quite realize was a dog) to a dance as her date, and she punched out someone who made fun of him (and as Snoopy noted, he bit the chaperone on the leg). Schulz usually created his humor by constantly thwarting his characters' desires, but it seemed as though he didn't quite have the heart to do that to Peppermint Patty. She really seemed to be living in a different world than the other regular characters in the strip.

Speaking of the other regulars, they don't shine quite as brightly in this volume. Lucy, the unquestioned star and irritant of the book for many years, is reduced to more of a side character with few extended storylines. Schulz really tabled his more obscure characters like 5, Shermy, Frieda, Patty, Violet and Pigpen, especially with more vibrant characters like Peppermint Patty to explore. That said, characters like Linus and Sally get some great segments. Sally's blustery frustration with the entire world (and school in particular) draws some of the biggest laughs, especially when she yells at her brother for not knowing answers to ridiculous questions. Linus gets mixed up with Miss Othmar's teacher's strike and starts becoming increasingly cynical.

Schulz noted that every one of his characters represented an aspect of himself. Lucy was his angry id, Snoopy was his adventurous daydreamer, Charlie Brown was his neuroses and fears, and Linus was his thinker. In this volume, Linus seemed to be processing Schulz' own feelings about becoming the world's most famous cartoonist and a multimedia star. It's clear that he was somewhat bewildered by the attention and started to question his own process. There's a strip where Linus writes a fawning essay about being so happy to be back in school. When he teacher praises it, Linus turns to Charlie Brown and says, "As the years go by, you learn what sells!" That's certainly true of this strip, as Peanuts' more whimsical aspects were obviously much easier to market than Charlie Brown's persistent melancholia. Later, when giving a teacher another fawning answer and Charlie Brown calls him out on it, Linus shrugs and says "Is it so wrong to make a teacher happy?" He might as well have said "audience".

In the face of Peanuts getting more and more episodic and losing some of its bite, Schulz responded with some of his most gut-wrenching moments for Charlie Brown. The sequence where the little red-headed girl moves away, with Charlie Brown standing there without even introducing himself, is heartbreaking. All the more so as Linus is screaming at him to move and do something, and becoming furious when Charlie Brown does nothing. When Charlie Brown starts to fantasize about seeing her in the future, Linus kicks him in the ass because he knows it'll never happen and he's tired of entertaining his friend's self-delusions. Those strips are remarkably bitter, and one can sense Schulz shift away from them with some bit of Snoopy silliness as a sort of antidote.

Nothing much goes right for Charlie Brown here: his baseball team is awful, he's terrible in school and even his baseball hero, Joe Shlabotnik, fails to show up at a sports banquet because he forgot the date and city. Lucy still abuses him hilariously, especially when she tells him horrible things that will happen to him in the future that he "may as well know now". Lucy is still frustrated by Schroeder, though their interactions lead to some of the liveliest strips in the book. In particular, Schulz gets into an unusually meta gag involving "spray-on Beethoven" that is much more formally playful than one would expect from him.

I suppose the best way to describe Schulz in this book is "restless". He'd gone through many years of spilling bile on the page and was looking to go in different directions. He was being pulled by contemporary influences, the potential of new characters, the commercial considerations of his work and the genuine affection he held for his older characters. He had completed the transition as master gagsmith to someone who created amusing situations and took his characters to some strange places. No individual strip past this era would pack as much punch as his earlier work, yet their cumulative effect still revealed a master cartoonist with an impeccable sense of timing and design. Again, the chronological arrangement of the strips, allowing the audience to see the passage of time and its effect on his creative choices, becomes a crucial element in fully understanding and enjoying them. The cumulative impact of these volumes is greater than any individual strip, and that's a testament to Schulz' devotion to his craft.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I'm stumbling across this six years after you posted this, and not seeing the responses you got on SeqArt, but I can't help responding to one statement: "Schulz assigned him a bird as a sidekick and pointedly named him Woodstock, devoting an entire strip to this revelation. It was an odd gag, as though making a reference to hippies was funny in and of itself." I think you're missing part of the reference here. Schulz had already established the little bird character, and had established him as a hippie years before Woodstock... and then the Woodstock music festival used a simplified bird character on their Arnold Skolnick-designed posters (you can see an image of it on the Wikipedia page for Woodstock.) It's that connection, that Woodstock is *that* bird, perhaps even that the music festival was named after him, that the was the joke.

ReplyDeleteHoly crow! You're totally right, Nat. When you mentioned the bird character on the poster, it instantly clicked in my mind--I had completely forgotten it. Schulz was ahead of the curve!

ReplyDelete