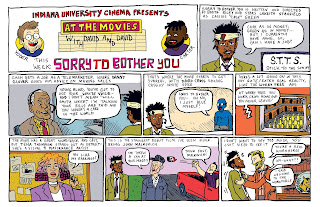

What wound up happening instead was working with writer David Carter as they'd watch a movie together. Yoder would do a strip a week and Carter would write a full review as a sort of package item. In their David And David At The Movies collections, their collaboration works nicely in bunches, thanks to their different tones, styles, and methods of working. It's not just that Yoder tends to be more succinct than Carter because he's a cartoonist, it's also that he synthesizes that knowledge like a comedian--much like Benson. So his reviews aren't beat-by-beat, but rather feature some visual gags, digressions, and fantasy bits, along with actual analysis of the films. Carter thoroughly critiques each film from the point of view of someone who knows a lot about film history, and it shows. However, his reviews are in the same spirit as Yoder's in that they start as a dive into the particulars of the film along with the prior work of the actors, writers, and directors. Along the way, the reader becomes more aware of the overall aesthetic point of view of both Yoder and Carter. I thought their reviews of Hidden Figures were especially on target, with Yoder bringing the laughs and Carter waxing philosophical about the history of biopics.

Amy Burns has a cute, spare style that lends itself both to absurdist humor and graphic medicine. With regard to the latter, she collaborated with writer Keilani Lime to do a book called No Spoons For You. This is a reference to Christine Miserandino's "Spoon Theory," a metaphor for those with chronic illness and/or disability to use in order to explain that they have a limited and variable amount of energy on any given day, measured in "spoons." When a person runs out of spoons for the day but still has things to do, they can "borrow" spoons from the next day at a high price, or simply be forced to stop, something that can be quite frustrating.

Lime puts this all in fantasy trappings with Burns giving the whole thing a positive sheen with her approachable and fun linework. There are gremlins that cause brain fog, supportive partners, managing medicines, and other struggles. There are funny repeating motifs (like a blanket, hot water bottle, etc being the main character Sunny's "best friend forever and ever"), but there's not so much a narrative so much as there a sense of trying to make readers understand what a struggle a single day can be without using a miserabilist approach.

Burns' own work tends toward poetic examinations of their own medical issues or absurdist fantasy shenanigans. You'll Never Find The Sun is an effective allegory about ontology, imagining a time not only before one's existence, but before the existence of anything. Then the big bang is compared to one's birth, finding one's parent, finding one's parent...but not finding the sun. It's explained that this comic is a reaction to discovering a diagnosis of lupus, a disease that is associated with sensitivity to sunlight. The problem with the otherwise beautiful presentation is that this expression of grief feels private; the connection to lupus, to being unable to find the sun in the comic feels entirely unconnected. There's nothing wrong with a poetic and private expression of grief, but the explanation afterwards felt tacked-on.

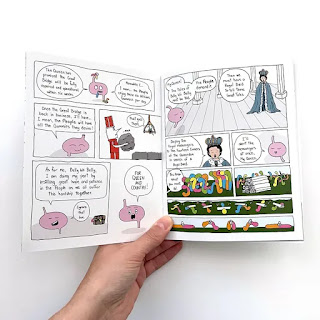

On the other hand, Belly Wō Belly: Bard Search, is absurd at every level. It's about a sentient stomach who is captain of the Queen's Royal Guard, who wears a human body as its armor. He's obsessed with gummies, who are both food and messengers, and his own ego. He begs the Queen to hire a bard to regale the People with tales of his glory, and Belly runs the search. He doesn't find a bard, but he does fill other open positions in the Queen's court, like Director of Waste Management. There are even sillier and delightfully self-indulgent digressions along the way, which only makes sense. If you're going to do a silly comic, you may as well go all the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment