I've been writing about Mike Dawson for much of his career as a mature artist, starting with his memoir Freddie And Me. In that nearly twenty-year period, Dawson has shown a tendency to never want to do the same thing twice. That's even been reflected in the fact that he's had multiple publishers during this time period. There's a proving curiosity in how he thinks about comics and the world that's reflected in his highly eclectic output as a cartoonist. In his most recent years, he's published two excellent YA books centered around a girl who plays basketball and her family called The Fifth Quarter. He's also been a prolific essayist and political cartoonist, publishing his work in The Nib and elsewhere.

Dawson is less interested in political cartooning as a form of polemic and more interested in a larger cultural commentary and exploration of issues from a personal point of view. It melds his interest in history and politics with memoir and storytelling. Above all else, Dawson centers everything around narrative, even in shorter stories. It's the main reason his work is so easy to parse and digest: one always has a sense of what the protagonist wants, or at least what they're struggling with.

That clarity is at play even as Dawson has proven to be one of the most restless of cartoonists in this period. One gets the sense that he wants to do every kind of comic at once, and in every kind of format. Indeed, Troop 182 was published as a webcomic, a series of minicomics, and a book; each iteration was slightly different. I think Dawson's hit on something with his recent minicomics collections of material from webcomics and his patreon. There's a cohesion to them that feels like he's been regularly cranking out minis for years like John Porcellino.

Fun Time, which was published in Spring of 2022, features a lot of Dawson's frequent meta-thinking. He often comments about the comics scene at various points in his career, but especially when he was younger and it was still dominated by white men. The cover, which features characters from his other comics as well as a fanboy drooling over an issue of Wizard, is very much in this vein. Much of this comic, however, consists of short, snappy, political vignettes. There's a strip about cops being obsessed with the Punisher and a disgusting way to diminish him. There's a lot of thinking about Generation X and its failures. Some of the best strips are about his kids, like an understanding of the childlike joy of cartooning and drawing for its own sake before one worries about what others will think. There is reflection on his practice as a cartoonist and what he's learned since he was a teenager (and how he gently lampoons himself over it). The best strip is a reaction to the Joan Didion memoir, The Year Of Magical Thinking, and how as a younger person he couldn't absorb its lessons about grief. In the wake of aging, of COVID, and of tragedy in general, Dawson remarks on his good fortune and quotes Didion: "Time is the school in which we learn." Dawson is at his best when he expresses self-doubt and vulnerability, and this strip shows how hard he thought about some difficult lessons.

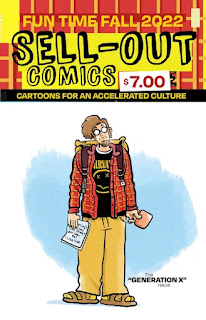

Sell-Out Comics (published in Fall 2022) is more pointedly about Generation X. There is limited utility in making cross-generational comparisons that don't take into account where someone is from, their ethnic and religious background, and so much more. It can be a lazy, broad brush with which to paint and make sweeping generalizations about things. That said, the temptation is understandable and some of the lived-in experiences he describes were things that were generalized for others. For example, he notes that the show Stranger Things, set in the mid to late 1980s, makes a point of scrupulous adherence to cultural references, yet as Dawson notes, there is no overt and showy homophobia among that group of boys. He points out how the 80s and early 90s were astoundingly reactionary in this regard (especially after the gains of the 1970s), and how remarkable so many kids today are in their enlightened acceptance, especially in the face of a newly reactionary right.

He discusses this further and says that a big difference between now and the 80s is that there wasn't a narrative of questioning the establishment as part of the larger cultural discussion, and points to events like Ronald Reagan's 1984 landslide and cultural touchstones like Rambo. The voices didn't have to be as loud or as violent because there were fewer voices speaking up against them. He also notes the contradiction of glam metal presenting its stars as at once hyper-masculine but looking utterly feminized as one of an almost unconscious revolt against masculinity. And he says that Generation X is the most complicit in fomenting the reactionary responses to a new enlightenment; I think this has less to do with Gen-X's supposed detachment and much more to do with a function of age, race and role in a capitalist state; again, this is a symptom of drawing too neat a series of assumptions about a particular age group. There are simply too many unexplored variables to make the kind of assertions that Dawson puts forward--unless one is only counting white people. Dawson's other observations about rhetoric being meaningless to fascism are spot-on, especially a joke about document storage that ends with him being in line to get shot.

Dawson puts himself on the line with his opinions, and he's developed a style that seems to fit it. It's loose, cartoony, and doesn't fuss over details. He uses color to add weight and texture to his pages, and keeping his line loose makes sense for this approach.

No comments:

Post a Comment