Hayley Gold's debut graphic novel, Letters To Margaret, is a crazily ambitious hybrid of comics and crossword ephemera with an avalanche of puns, wordplay, eye pops, and so much more. Gold's reach exceeds her grasp in a number of respects, but it was a dizzying and invigorating experience reading her attempt to throw the kitchen sink at her reader in the sheer number of verbal and visual devices she employed.

Let's unpack all of that a bit. Gold's formal ambition was staggering. The basic plot concerns a Columbia journalism student named Margeret "Maggie" A. Cross, a crossword puzzle enthusiast and blogger about that subject. She's relentlessly and painfully self-righteous, judgmental, and irascible, but she also has a razor-sharp wit and a strong point of view. The other protagonist is Derry Down, a grad student and her TA in a journalism class about column writing. As a Black grad student and fellow crossword enthusiast, he's sensitive to the way the New York Times crossword marginalizes people of color. As the gold standard puzzle, it bothers him to be reduced to words like AFRO and to see clues related to Aunt Jemima. The lead blogger on the site was his mentor, journalism professor Lewis Dodgson (a sly Lewis Carroll reference), who wrote as Vox Populi. Another crossword blogger (a subculture within a subculture, not unlike comics criticism), Maggie eviscerated Vox as being too PC. When Derry realizes that Maggie was the blogger (she went by Anna Graham, and he by Mr. Lear), he wanted to get back at her. Things go in some surprising directions, as conflict can create sparks of romance as well as conflict.

The core story and motivations are all relatively simple. Maggie is a harsh critic, but she's stung by rejection--and specifically having her crossword rejected by the NYT. Derry simply wants to find ways to make the crossword world feel more inclusive. Gold adds layer upon layer to the plot and the structure of her comic in order, in some sense, to approximate the chaos, complexity, and playfulness that goes into constructing a crossword puzzle. It's also about how two individuals will always see the same series of events with vastly different points of view, but that it's possible to make connections that bridge that communication gap if you make yourself open and vulnerable.

So the first thing that Gold does to communicate this is make it a flip-book. About fifty pages are devoted to the story from Maggie's point of view, and when you reach the end, one can flip the book over and read the same essential narrative, only from Derry's point of view. Considering how much of the book is subsumed by thought balloons, the reading experience is quite different, as the reader becomes completely immersed in the point of view of each character and slowly sees them navigate that gap.

That alone would have been plenty. However, there's an additional plot device and mystery as Maggie starts getting letters from Margaret Farrar, the (deceased) crossword puzzle editor of the NYT for 27 years. "Margaret" writes as though Maggie sent her the crossword puzzle that was rejected and wrote encouraging words. This was all the doing of her junk food video-making roommate Amanda, Maggie's former crossword commentary blogging partner.

Each chapter is headed by crossword puzzles that contain clues and spoilers for the chapter itself, and Maggie's own puzzle is printed several times as it evolves. That particular gimmick is extremely clever, immersing the reader in this particular hobby and culture in the most direct way possible. Gold doesn't stop there with her visual tricks, as she makes frequent use of internal notations and metacommentary. Those comments are frequently made by talking arrows, one white and one black, named Ebony and Irony. They comment on the plot, the thoughts of characters, crossword clues, and everything else, adding another level of visual and decorative wordplay to the proceedings. On top of all that, Gold throws in some magical realism for good measure, as several of the characters are literally able to read the thought balloons of other characters, while others appear as hallucinations, bringing snacks along to enjoy.

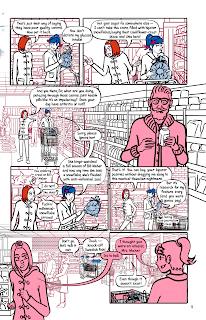

Throw in Derry's fascination with the nonsense poems of Edward Lear and a heavy dose of history regarding crossword puzzles, and you'd have something that even the most confident and experienced visual artists would find challenging to present in a clear, coherent manner. The biggest problem with the book was its design. The pages were absolutely crammed with text, suffocating and surrounding entire panels' worth of art with layer upon layer of text. While swimming in wordplay was part of the point of the narrative, the reader never got a chance to breathe. Gold has also noted that Amy Sherman-Palladino, creator of Gilmore Girls, was an inspiration with regard to dialogue, but even that hyperverbal show had interludes that allowed everyone to take a breath.

Gold does combat this problem with her cartooning, and it was often successful, especially as my eye adjusted to the frequent walls of text. Specifically, she kept her line simple and functional and used color as character signifiers, guiding the reader's eye across the page. That allowed her to integrate her comics with crossword puzzles; the crosswords took on a pleasing decorative aspect. However, this approach did not work at all when she plopped a blog down on the page, especially with the text being so small. This was another design problem; this book needed to be printed at a much bigger scale. Each page was based around an eight-panel grid, but being printed at 7" x 10" crammed too much information on one page. A 10" x 14" scale, more in line with a European album, would have made the pages breathe a bit.

Letters To Margaret feels like a young cartoonist bursting with ideas and trying to cram them all into one project. The marginalia, the metacommentary, and other, similar elements distracted from the book's most interesting innovations. Gold's ability to alter the narrative in both sides of the flip book was astonishing and allowed her to focus on the most important aspect of the comic: its characters. Derry and Maggie were both unreliable narrators and were hard to like, but that was part of their charm for both the reader and each other. Letters To Margaret, at its heart, is about the dangers of being so hardened in one's beliefs out of spite that it prevents you from even trying to understand the perspectives of others. Derry and Maggie were both funny, sweet, nasty, and unbelievably witty on their own; they didn't need the marginalia to make their story shine. Gold has a remarkable facility with dialogue and wordplay, giving even the most affected and stilted wordplay emotional depth. Maggie and Derry used their hyperverbal qualities as a mask for their deeper feelings and insecurities, but they also used it as a form of playful, loving interaction.

Gold clearly has a bright future with regard to these kinds of character dramas, as her own sense of humor, playfulness, and eager willingness to innovate will no doubt continue to transform what could be dull talking-heads panels into something far more interesting and challenging. That said, I would hope that she focused her cartooning on the most important part of visual storytelling: the characters. How they interact with each other in space and fluidity of movement, in particular, are things that would enhance Gold's way of creating a beautiful verbal dance between her characters. I'm fascinated to see what she tries next.

No comments:

Post a Comment