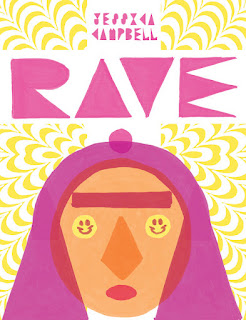

The genius of Jessica Campbell's work is her fastidious attention to detail. Her first two books were broad satires of gender, culture, and art that landed hard precisely because of how much she knows about art institutions and how easy it was to write a funny bit of feminist sci-fi. With Rave, however, Campbell moved into more serious territory in exploring how evangelical Christianity, by design, controls every aspect of its parishioners' lives and creates trauma and dysfunction. Campbell's attention to detail with regard to the church in this story is almost painful to read; it's the sort of thing that only an insider could have explained.

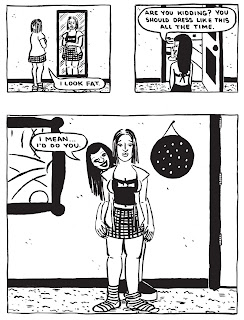

Rave is the story of two teenage girls, Lauren and Mariah. Lauren is a good-natured, church-going girl who attends a fairly big evangelical church in what seems to be a suburb or smallish town. It's the kind of community where people tend to know each other--like it or not. Mariah is her classmate, a "bad girl" reputed to be a witch. When they are paired together on a school project on evolution, they decide to do a sleepover at Mariah's place, since Lauren's parents are offended by the very concept of evolution. Lauren's drawn to Mariah's devil-may-care attitude, and Mariah is drawn to Lauren's hidden potential. They slowly fall in love, the kind of romance that crosses naturally from close friendship into something physical. At a certain point, Lauren hears a sermon condemning same-sex marriage and starts to feel the kind of cognitive dissonance only a believer confronted with ideology that runs contrary to their lived experience can understand. She distances herself from Mariah and immediately regrets it, but it's too late.

In the book's superb climatic sequence, Lauren attends a Christian "rave" (which is hilarious in any number of ways, but more on that later) while Mariah hangs out with a creepy guy in the forest. In both instances, the girls receive forced and unwanted sexual advances from guys they trusted. In Lauren's case, she simply runs away from the dull boy who's hitting on her; it's implied she only agreed to go with him to the rave as a nod to trying to fulfill the role the church wanted for her. In Mariah's case, she runs off into the woods and accidentally drowns in the river; it's implied that she was not just drunk, but drunk from something the guy brought and had drugged. Lauren eventually sees through all of the hypocrisy and storms out of church, smoking a cigarette from a pack she found in the garbage--a small tribute to her friend.

It's the astounding verisimilitude of the cloying, manipulative quality of the church that makes this such an unsettling read. Christianity's ace in the hole has long been its ability to co-opt local religions and customs throughout history, repurposing these familiar mores and stripping of their original meaning while retaining the trappings. This viral quality can be seen in modern iterations of worship in churches using lingo and tropes familiar to kids while using the latest technology, like headset microphones. The core of the ideology remains unchanged for evangelical Christianity in particular: salvation can only come through Jesus, same-sex relationships and pre-marital sex are evil, Satan is actively trying to get you to stray off the path, etc. This played out in the DJ who ran the Christian rave, saying that Jesus was the first raver and wants people to dance and move--but not have sex. The use of lingo like "Can we talk?" in an attempt to dress up the archaic and repressive nature of these beliefs is the essence of this playbook, and Campbell just nails painful detail after painful detail. It would all feel like an exaggeration if it wasn't 100% true.

There's a scene early in the book that reveals just how much the church was simply theater. The daughter of the pastor (who of course revealed his struggle with masturbation that he supposedly conquered) got knocked up and was forced to go through the pregnancy. She was called onstage to repent and talk about God's love. When Lauren said hello to her at school the next day, the girl (smoking a cigarette while pregnant) simply said, "Fuck you." It was all a charade, all for show. Love, mercy, and compassion were stage dressing for controlling the lives of the believers. Lauren didn't truly understand this until the end of the book, and who can blame her?

Campbell has her limitations as a draftsman, but it doesn't matter much because her skills as a cartoonist are so sharp. Her use of gesture is top-notch; there's a scene where Lauren is talking to Mariah on the phone, sitting in a plush chair, moving in different positions. Her relaxed poses in each panel reveal just how comfortable she was feeling with her best friend in ways that felt natural until the authority of the church told her otherwise. Similarly, the plastic quality of the pastor and rave DJ are reflected in the way they have their hair sculpted. Her satire is as trenchant as ever in Rave, but its surprising emotional depths point to her evolution as a cartoonist.

No comments:

Post a Comment