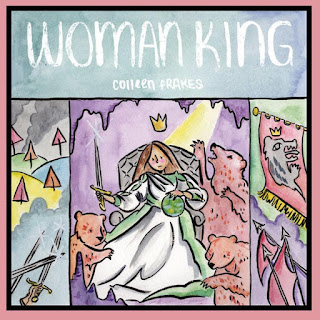

Ten years ago, Colleen Frakes published her breakthrough comic, Woman King. It earned her a Promising New Talent Ignatz award, and she's been producing excellent work ever since then. Woman King came out in various minicomics forms until its final original iteration was published, and I reviewed that here. Frakes just published an expanded tenth-anniversary edition for which I wrote the introduction. The book is printed at a larger size, giving Frakes' brushwork even more of a chance to breathe. There are also two new stories. There's a full-color story that was printed in mini-comics form back in 2008 that's almost psychedelic in its construction, as Frakes forgoes line in favor of white outlines of intense color bursts. The story itself is based on the same kind of logic that drove the war in the main story: winning the war is everything, and the otherwise innocent girl must be driven to do horrible things to help win it. In this case, it's killing a dragon and having her eat its brain. Of course, the "dragon" was a car and its "brain" was its engine block.

The final story is a sort of recapitulation of the story as well as an expansion of its mythos. A young man travels to find the child who will lead them to freedom against the animal army led by the bears and its Woman King, only to see that some beasts were fighting on the child's side. There's then a long interlude as the pilgrim reads about the ways in which different cultures regarded bears and their relationships with women. It was enough to get him to distrust all bears (and eventually get chased by one). It's an interesting denouement because it essentially does two things. First, it establishes that as a result of the events of the story, a mythology was built around it. That mythology only served to further create a sense of us and them through its twisting of ideas and events. Fake news, as it were. Second, it reveals that the cycle of violence hinted at in the end of the main narrative came to pass, becoming all the more terrible in each new iteration. Trauma handed down through generations causes an exponential amount of harm, as the farther from the initial trauma and the truth around it one becomes, the more important it is to rely on myth and unreliable oral histories. When you're living in a permanent state of emergency, it becomes impossible to discern what is truly dangerous.

I've been reviewing Sean Knickerbocker's Rust Belt minis for nearly a decade now, and they were just recently collected by Secret Acres. While the individual issues and stories were quite good on their own, the collection has a poignancy that's greater than the sum of its parts. Like Chuck Forsman and Dakota McFadzean, Knickerbocker writes stories about the desperate, the hopeless, the doomed. The cover, featuring what looks like a double-wide at dusk, gives the reader a visual taste of the stories found within. The first couple of stories follow Chad, a high school loser who's picked on by assholes because they think he looks like Kurt Cobain. There's no happy ending for him, as the girl he has a crush on has to move away, he ignores the girl who clearly has a crush on him, and his posed disaffection bites him on the ass in school. When we see him again, he's a vagrant hanging out with a sketchbook in a grocery store parking lot. That sense of continuity in the book makes each individual story more effective and memorable, as the reader is interested in seeing how things are connected.

When Knickerbocker shifts to stories about adults, their fates are even grimmer. Bradley is a store assistant manager who is demoted when new ownership comes in. David is a drunk who can't get past childhood trauma. Jason is a plumber whose alt-right rants go viral and gets manipulated by media trolls. Knickerbocker presents them warts and all, as they are all deeply flawed. They lack empathy, especially for those who care about them. They blame others for their problems. They rightly bemoan a lack of resources and fairness but can't see outside their own needs. Knickerbocker seems to be arguing that "real people" have it hard in part because of the forces of global capitalism, but he also seems to be saying that personal solipsism and an inability to see from someone else's point of view are also culprits for misery. In the last chapter, Jason's wife Meghan asserts her personal agency while allowing for her husband's beliefs, but is justly angry when he gets doxxed and they have to scramble to make a living. Her own anger at how she's treated at work because she's a woman add an important element to the story. All throughout, Knickerbocker silently comments on the idea that no matter the struggles of these characters, they still don't understand their own levels of privilege, either as men or as white people. Most of the characters have the ability to alter their circumstances but are unwilling to do so, never once allowing that others might have it worse than them.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment