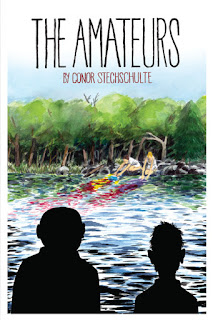

The Amateurs, by Conor Stechschulte. I reviewed the self-published version of this book already, but the updated version has a few changes that are worth mentioning. Stechschulte tossed out the original prologue involving a couple of men finding a severed head that was talking. Instead, it became two young women who found the head near the sinister river, a shift that became especially effective thanks to the addition of some new interstitial material in the form of (presumably) the same woman's library. Adding the diary sequences also helped tie in the secondary plotline of the two women who visited the butcher's shop and added more mystery and depth to the symbology of the river. Stechschulte also makes the whole thing in black and white, removing the abstract, color interstitial pieces that divided up the story and replacing them with the diary pieces. The story is still entirely ambiguous, it's just ambiguous now in a different way. The book is so disturbing for two reasons: first, because the characters in the story are constantly either forgetting what's happened or pretending to forget what's happened in the interest of preserving a veneer of sanity and reality as usual. Second, the river is a powerful force in this story, as the normally beneficial aspects of a river are not only absent, Stechschulte implies that the river is a tool of an actively malevolent force. The book is so disturbing not just because of the gore (which is still largely played for laughs), but because of the sinister, silent forces that inspired it.

Class Photo, by Robert Triptow. Triptow is a long-time underground artist and one of the former editors of the crucial Gay Comix anthology. The concept behind this, his first book, was the explication of an old high school class photograph from the 1930s, imagining the names and backstory of every single person in the photo (and several who weren't). Triptow hit upon an important narrative idea, which is that the best part of any story about high school or college is the epilogue, where we learned what happened to each character. Well, this book consists almost entirely of that, with just enough information to make the reader aware of what they were like in high school. What Triptow does in the course of this book is get set silly and then sillier as his characters endure typical high school cruelties and then go on to live atypical lives. Triptow's writing is sort of like long-form improv, as he weaves characters in and out of each other's lives, makes callbacks to earlier jokes and characters, and drops one narrative only to pick it up mid-stream later in the book. With each person in the photo providing a blank slate, he was able to create a remarkably complex (if totally nuts) series of plots and subplots.

Take Rudolph Valentino Kominsky, for instance. Ridiculed by other kids for his name, he vowed vengeance on them all and became a spy for the Nazis during World War II. His narrative drops away until we meet Fritz Beauhacker, "the only US civilian killed during World War II". Kominsky winds up shooting him. Then there are the members of the Bad Girls club, Stella Jakov and Trixie Trotlikk. A gay character doesn't notice the girl who's in love with him because he's in love with a boy who doesn't react well when a pass is made at him. Triptow makes it work in part because his knowledge of the era is exacting enough that he could make references that made sense and became a key component of his gags. At the same time, he was loose enough to let flights of fancy take him wherever they directed, be it about clairvoyants, exchange students, ultra-rich kids, thick accents and being so unmemorable that folks didn't even know she was there. There's no question that Triptow's art does a lot of the heavy narrative lifting in this book, adding a surprising amount of warmth to go along with caustic satire of New York bourgeoisie.

Triptow's art reminded me of any number of cartoonists, but Robert Crumb is the most obvious. There's also shades of Roberta Gregory, Justin Green (in a big way) and others in his cartoony but still naturalistic style. It wasn't so much that his drawings were inherently funny (like a Will Elder0, but rather that he drew funny things that disarmed readers with charm, wit and the occasional streak of cruelty. One senses that he could have made up new characters and folded them into loose narrative indefinitely, but the further the book went on, the more that Triptow started to close the ranks a bit so he could tell the final story. Triptow's hilarious mocking of hypocrisy is at the heart of the post-high school lives of these characters, as he is more than happy to make fun of familiar high school tropes and melodrama. For a quirky (almost) vanity project, it's remarkable how wide-raging and all-expansive the world Triptow created is. It's also consistently funny from beginning to end, as Triptow's exaggerated style works in concert with his instincts as a gag man. It's a testament to his skill that he was able to turn a solid high concept into reality on page after page of this ridiculous novella, as well as the fact that despite a certain expected nastiness on the page, Triptow shows a remarkable amount of empathy for his creations.

No comments:

Post a Comment