This review was originally published in 2007 at sequart.com

**************************

Producing a viable and interesting adaptation from one form of art to another is one of the most difficult and thankless tasks for an artist. A novel is not a play is not a film is not a comic--each art form has its own unique strengths and limitations, and what gives one narrative a unique flavor in one art form can be lost in translation when it's adapted to another.

In comics, there has been a long tradition of adapting works of literature into comics. From the venerable Classics Illustrated (soon to be resurrected) to EC printing Bible stories, the primary appeal for these adaptations was providing the general public an "easier" way of reading classic stories. The problem with such translations is that they be necessity must sacrifice the richness of the prose; the better the prose, the more the comics version can suffer. A remarkable illustration that replaces a particularly eloquent bit of prose can be a powerful experience on its own, but it's not the same experience as reading that prose. On a more practical level, there simply weren't enough pages available in a standard comic book to fit in everything from a novel, so huge chunks of story and characterization were often cut. The art in these adaptations often looked hacked out, which is not surprising considering that they were produced on a tight deadline.

The Graphics Classic line has tried to circumvent these difficulties by adapting well-known works of genre fiction that lend themselves well to a propulsive comics narrative. Series editor Tom Pomplun has also gone out of his way to use short stories rather than butcher novels. The line of comics includes HG Wells, Bram Stoker, Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, O. Henry, Jack London, Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle and others--so the stories are generally plot-driven, with larger-than-life characters, and often a bit of action. Considering that many of these stories later inspired pulp novels, which in turn inspired early comics, one can see that Pomplun has made some shrewd choices in his choice of subject matter.

Given that Pomplun has carefully chosen the subject matter and has recruited a number of comics' best artistic talents to illustrate the stories, how do these volumes hold up as comics? Let's begin with the Lovecraft volume. While there are some truly excellent artists in this volume, including Matt Howarth, Richard Corben, and Rick Geary, I'd say this volume doesn't quite succeed as a comic. That has more to do with Lovecraft than it does with the artists. Lovecraft's characters tended to be ciphers whose purpose was simply to reveal a small glimpse of the horrific world that he dreamed up. That led to another problem with translating his work into comics: his stories are full of descriptions of things seen that defy description because they're too horrible to comprehend. These things are always just hinted at , just beyond our understanding. Viewing them on a page removes the mystery that gave Lovecraft's prose power and dread. In comics form, without the weight of doom that Lovecraft brings to bear, the stories are more predictable and the visual payoffs seem trite.

The other problem is that Lovecraft's stories are often short on dialogue, leading to a number of narrative-heavy captions. In the adaptation of "Herbert West: Re-Animator", the level of text used threatens to overwhelm the comics portion of the story. Indeed, it crosses the line between comic and illustrated story. The most successful story in the book as comics is probably the first, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth". It works for three reasons: it's more character-oriented than the rest of the book, the slow transformation into horror is kept at an individual, human level rather than the apocalyptic levels implied in other Lovecraft stories, and the grotesque art by Simon Gane is a fitting match for this tale of a young man who slowly realizes his hideous destiny.

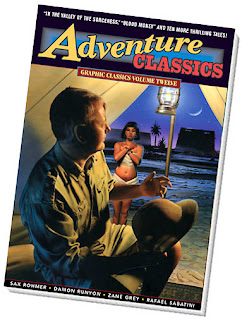

Much more successful in the transition from prose to comics is Adventure Classics. The sheer variety of material and artistic approaches actually improves the stories, some of which are so familiar that they cross over into cliche. For example, Mary Fleener's Cubismo technique is a nice match for the old Kipling poem "Gunga Din", and Hunt Emerson's exaggerated figures bring "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" to life. Emerson uses the verse as captions for each panel, but he packs the panels with so much detail and animation that they take on their own life. Along the same lines, Antonella Caputo & Nick Miller amusingly adapt Doyle's "The Crime of the Brigadier", which is part adventure story and part French-British humor. It's one of the few stories in the book that doesn't have a predictable ending. It's not really the fault of these stories that they're so formulaic; indeed, these authors created many of the formulae that are so familiar to the modern reader. Still, those stories that rely heavily on twist endings that most readers can see coming lose a lot of their impact.

The other standouts are Damon Runyon's "Two Men Named Collins" (adapted by Pomplun and drawn by Noel Tuazon) and Johnston McCulley's "The Stolen Story" (adapted by Pomplun and drawn by Chris Pelletiere). Both stories have a grimness to them that made them memorable and feature characters that linger in one's mind. The former is typical Runyon, about a hard-bitten soldier who lives a rough life, but winds up displaying surprising humanity. The latter (penned by the creator of Zorro), is about a man who so desperately wants to become a writer that he steals and rewrites the story of a drunken acquaintance of his. While the story is accepted and published, it unleashes a wild chain of events that result in the writer's doom. Both stories have a grittiness and ugliness to the art that perfectly matches the tone of the prose.

The third volume, Gothic Classics, has several stories that would go on to have a huge influence on the future of gothic fiction. "Carmilla", by J. Sheridan Le Fanu, would go on to inspire Dracula, though there's not much in here that's surprising for a modern audience. Lisa K Weber's cartoony grey-tones were an interesting match for this overheated bit of vampire fiction with lesbian overtones. Speaking of overheated, "The Mysteries of Udolpho" is sort of the world's first romance novel. Wildly popular at the time, its fainting heroines, mysterious castles, rugged heroes and sordid romantic details would become familiar to readers everywhere in story after story. Its adaptation here is perfunctory, getting across what a reader needs to know, but it's mostly of interest because of its historical importance and as a set-up for the best story in the book.

That would be Jane Austen's "Northanger Abbey", adapted by Trina Robbins and Anne Timmons. That's a team that's worked together for quite some time, and it shows. "Northanger Abbey" is a parody of "Udolpho", and the main character actually references it in hopes that her own life would resemble that gothic tale. The delicacy of Timmons' pencils are perfect for this spoof of manners, and Robbins adeptly takes us through the story's twists and turns. It's Austen's wit that towers above all, and I was surprised at how well it translated into comics form.

The other story of note is "At The Gate" by Myra Jo Closser. It's most notable not for the very slight story about dogs waiting outside the gates of heaven, but rather for the welcome return of Shary Fleniken. I've long admired her work, and she does a nice job in making the dogs in this story expressive.

Tom Pomplun has taken on a unique project in comics, and while it's not always successful, it definitely is a worthy attempt. If nothing else, Pomplun is keeping alive stories whose influence is taken for granted today. His willingness to use a wide variety of graphic styles makes the comics worth looking at in addition to reading, though it would be nice to see ever more idiosyncratic approaches to the material. I'd be curious to read his attempts at adapting better authors, like Twain and Bierce, to see if the impact of those stories is sustained through their transformation into comics. At some point, I'd love to see him take on authors like Vonnegut, Chesterton and Asimov. While most of the stories he's adapted have been genre stories like mystery, horror, science-fiction, detective and the like, it would be interesting to see a volume built entirely around humorous short stories. That would be an excellent way of making use of another long tradition of cartooning.

Friday, March 29, 2013

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment