Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Minicomics Round-Up: Stanton, Rae-Grant/Winslow-Yost, Kyle, Lee, Five True Fans, Bird

Gnartoons #1, by James T. Stanton.Stanton is great at drawing monsters, robots and monster-robot hybrids. He then accentuates these highly detailed, almost manic drawings with bright, lurid colors that almost overpower the reader before one adjusts. That's certainly true of the lead story in this one-man anthology, "Subterfuge", where a pet robot and its owner are ambushed by a huge network of threatening machines. Stanton can stop on a dime and go back to black & white for a story about an aggrieved classroom pet being accosted by a band of crazed kids, emphasizing the barbaric and grotesque nature of children who are let loose in packs without adult supervision. Stanton then pauses to consider his own obsession with drawing monsters, wondering if it's something he gets out of his head or if that obsession is leading somewhere darker, all on a cleverly-designed page designed to keep the reader off-balance with triangular panels and sickly colors. Stanton really throws the kitchen sink at the reader in this sampler, using highly realistic drawings in one disgusting strip about San Francisco and varying his color schemes in a more poetic strip. Stanton has the potential to be a major talent, and these minicomics offerings are an interesting way for him to warm up in public.

Steel Sterling, by Gabriel Winslow-Yost and Michael Rae-Grant. This is the first comic by this writer-artist duo, and it's an impressive debut. Riffing on Charles Biro's Golden Age creation, Steel Sterling is a lab-created hero who goes on a psychedelic spreed of mayhem. There are three different operating levels in this comic. First, there's the constant, kinetic, left-to-right ass-kicking of the protagonist, who wades through ninjas, robots, grid-covered rooms, strange animals, axe-handed mustachioed-men sitting on toilets and other such nonsense, all in lurid, day-glo colors. Second, there's the earnest narrative captions that follow him around, commenting on his fights, offering advice and evaluating the evil of his opponents. Finally, there's the static, languid scenes of arch-foe the Black Knight (done in green as a counterpoint to the preponderance of red found in this comic), who counter-intuitively gets the center grid on every single page. This is counter-intuitive because as Frank Santoro would tell us, the center grid is where the eye goes to first, looking to balance the other figures. By inserting a very slow-moving narrative as the center of our attention on every single page, GWY and MRG subvert both reader expectations and the implied narrative of the story, telling the reader that the hyper-violent adventures of the hero are less important than this green-lined figure eating breakfast. This helps set up the final-page gag while foreshadowing the treadmill nature of Steel Sterling's mission. This is definitely a modern take on Golden Age tropes, as the authors seem to borrow as much from Michael DeForge as they do from Biro or even iconoclasts like Fletcher Hanks. I'd be fascinated to see what this pair of artists comes up with next.

Bird Brain Comix #1, by Bird. The otherwise anonymous Bird's comic is the first I've seen from Tom Hart's Sequential Artists Workshop in Gainesville, Fl. It's the first comic of any kind I've received from my home state, which is not exactly a hotbed for alt-comics talent. In a spectacular explosion of self-deprecation, the artist notes (on the cover, no less) that this comic is "overly designed, inarticulate and poorly drawn". Of course, this issue is none of those things, even if it's obvious that this is an early effort in the artist's career. Instead, this comic owes a lot to long-form improv, with the added advantage that because Bird's not explicitly going for laughs in every strip, certain comics that stand on their own as serious statements are later revisited for both tragic and humorous results. Of course, in this comic, the "jokes" come at the expense of downtrodden characters victimized by unfeeling teenagers out to get wasted and violent. There's a matter-of-factness running through this comic as a robot separated from his body and the roadside assistance of Sasquatch are treated fairly nonchalantly. The one thing that drove me crazy about this comic was Bird's insistence on using a thin line and leaving a lot of white space without spotting a lot of blacks or varying his line thickness. He also winds up relying too much on effects like zip-a-tone to fill in some of those big white spaces, and the effect is a greyish, unattractive page. Still, there's an interesting mind at work here, one that just needs to get back to the drawing board and continue to experiment.

Them's The Breaks, Kid., by Cassie J. Sneider, MariNaomi, Ric Carrasquillo and Tessa Brunton. This anthology is by the Five True Fans collective, and the theme of this one is essentially misfortune. This is a mix of comics and illustrated essays, most of which are quite personal. The cover is hand-stamped with an image from each story, which is one of those crazy yet endearing things about minicomic-makers insane work ethic. Sneider's "Bad Decisions" is a sound choice for lead-off story, given that it's grim but hilarious. The grim part regards Sneider's life-long near-poverty, meaning she's rarely had access to things like health or dental insurance. There's a bit where she's left to wait in a dentist's office with a painfully bad tooth for hours, until she decided to steal something from the exam room for every ten minutes she was kept waiting. That led her to possess some novacaine, which led her to ingest it into her face because she thought it might arrest an allergic reaction to antibiotics. It's a horrifying but undeniably hilarious image.

MariNaomi kicks in yet another variation on a story she's written about an ex-boyfriend who disappeared years earlier, this time including an epilogue about seeing his best friend as a homeless person and trying to ignore him as he now seemed clearly out of his mind. This set up the tragic end of the man killing himself by throwing himself in front of a subway car. The essence of her section dwells on being haunted by once-powerful connections suddenly disappearing forever, an event that has a powerful effect on one's memories of the original events. Carrasquillo's cartoony line focuses on the ways in which marketing is subverted by children, by how faux-humble introductions to one's heroes masks seething jealousy, and a gag where appealing to the true force behind the water bill is an imposing process. His contributions were well-drawn and cute, but seemed radically out of step with the rest of the artists in the book; if anything, they felt slight compared to them.

My favorite part of the book was by Tessa Brunton, who did a number of crisply-drawn comics about her battle not only with chronic fatigue syndrome, but the emotions and self-hatred that often accompanies a disease whose main symptom involves an inability to summon the energy needed to deal with a standard person's day. There's one powerful strip about her desire to give into her bitterness, her anger, her desperation and her hatred of her own body. Then she owns up to the real reason why she tries to stay positive: because "bitterness is repellent" and "I don't want them [her friends and family] to all go away." That's a powerful statement, but Brunton also notes that simply drawing these feelings and printing them is a kind of emotional therapy, one that certainly draws other people to give her sympathy but mostly makes her understand that others do care. Brunton's lack of relentless cheerfulness about her condition is refreshing and funny, giving her license to make some pretty dark jokes. (When an internet support group scolds her and tells her she can do whatever you put your mind to, she replies "Indeed I can" as she holds a gun to her head.) Between this suite of strips and her comic Passage, Brunton's beautiful and light penciling style and sharply sardonic wit have made her a talent to watch.

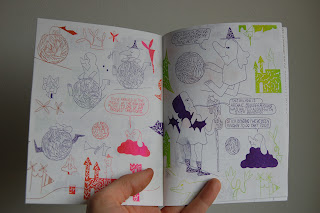

Distance Movers #1 and #2, by Patrick Kyle. This is straight-ahead surrealism, as Kyle puts together a comic that for all intents and purposes is a genre science fiction comic, yet doesn't conform to standard fantasy tropes. Instead, Kyle's drawings (all printed in color ink, one color at a time) are rubbery, highly simple but stylized and mostly static on the page. The sort of lumpy surrealism that flows from the Marc Bell tradition in Canada is present in this work, though this story of Mr. Earth visiting a backwoods village and later taking one of its denizens to a hyper-advanced big city zips readers through an increasingly complex plot that's more like Matthew Thurber. There are some wonderfully abstract sequences of pure, non-narrative shapes that represent a sort of virtual art gallery that fit snugly in with the rich and warm visuals in the rest of the comic, as the color printing (done on the highly versatile Risograph) simply grabs the eye and doesn't let go. Kyle combines simplicity and clarity of line with complexity of design and narrative to creative a beautiful new series.

Temple, by Jun K. Lee. This is a quiet, poetic story about a man finding god in another man's ear and a sort of phenomenology of what this experience is like. Lee's sparse, thin line reminds me a bit of Souther Salazar's delicate, almost fragile images, and Lee's equally delicate lettering has a strong visual impact as well. The lettering is just a little scrawled--it's entirely legible, but it's small and requires a bit of concentration to parse it. That actually folds in nicely with the increasingly strange images we're presented with in this 8-page comic, as the narrator focuses his attention on a small dot that provides a direct line between him and god. The end of the comic raises the issue of who is entitled to see god and for how long, especially since the narrator steals the ear to keep for himself. This brief story doesn't wear out its welcome and is remarkably clear and coherent, given the strange places it goes to.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment