***

Over the past two years, there's been a series of comics that have mostly flown under critical and popular radar: the Ignatz line. Beyond their actual content, each issue is a triumph of design. The first thing one notices is their unusual size and packaging: they're 8.5 x 11.5 inches and each issue has its own dust-cover. Each issue is 34 pages long and is printed on light card stock. The look of each individual issue varies on the content, but in general they range from black-and-white to one or two color washes to full color. They're all beautiful art objects, simply gorgeous to look at and hold. It's hard to imagine a more attractive way to present single-issue comics. Still, in this age of graphic novels getting the bulk of attention from the media, it's unfortunate that this series hasn't received more acclaim.

Of course, it hasn't been entirely ignored: Gipi got an Eisner nomination for WISH YOU WERE HERE #2, and Kevin Huizenga's GANGES received a lot of buzz in alt-comics circles. Another reason why this line hasn't received the acclaim it deserves is that many of the artists are unknown in America. That's a function of the goals of the series' editor, Italian artist Igort. His only prior work translated into English was FIVE IS THE PERFECT NUMBER, a elegant-looking gangster story published by Drawn & Quarterly. The concept behind the Ignatz line (inspired, of course, by Ignatz the mouse from Krazy Kat) is combining the best of American and European artists, giving each the freedom to do as many issues as they wish in their own series. This article will discuss each of the series within the line. While Igort has striven for a consistency of design in how the line looks, there's an enormous amount of variety in the actual subject matter and artistic styles published. Kim Thompson is doing the translations for the non-English work, and deserves special mention as one of the primary instigators and sustaining forces in the translation of European comics. At this point, most of the series are still in progress, but with a full two dozen issues in print, they certainly bear scrutiny.

WISH YOU WERE HERE

The celebrated artist Gipi, gaining greater exposure in America thanks to the publication of two of his graphic novels from First Second, stunned me with these two issues. The first issue, "The Innocents", is a classic example of his storytelling style. A master of gesture and expression, he mixes up a grey-wash style with a frantic scribble for flashback scenes. The story is also not unfamiliar: a man is traveling with his nephew and is visiting an old friend of his. The friend had a hard childhood at the hands of vicious authority figures and it scarred him for life. The interaction between past and present, as well as the way that children are forced to grow up fast in the most unpleasant of circumstances, is a running theme for Gipi. In particular, there's a sense that the past always catches up with us.

That theme is especially evident in the second issue, "They Found The Car". This masterful comic is as memorable for what Gipi doesn't tell us as for what he does. The plot is simple: a man awakens to a phone call in the middle of the night, and a voice at the other end simply says, "They found the car." From there, the man takes a drive with the man who called him, and they visit the house of the man who was supposed to dispose of this mysterious car, seven years prior. This kicks off a chain of events that are tautly depicted, leading to an ending that leaves the reader with a feeling of dread. Not just because of the events that are portrayed, but also because of certain theological implications that arise during the course of the story. Gipi leaves many questions unanswered in this story, weaving between an omniscient narrator and a first-person narrator to pages carried solely by their dialogue. The grey tones are perfect for evoking the feeling of angst and a sense of being out of place that driving around late at night in the rain brings. I've rarely read a comic that more intelligently portrayed suspense than this one. That said, it's the religious and philosophical undertones that wind up giving the story its real power. Gipi is simply a master, crafting accessible stories with enormous depth and vivid characterization.

BAOBAB

Series editor Igort is creating something very interesting indeed with this series. Scheduled to run at least eight issues, Igort has created simultaneous, seemingly unconnected narratives. Befitting an artist who achieved success publishing in Japan, one of the narratives concerns a young boy named Hiroshi and a village in 1910 Japan. At the same time, in the fictional South American island country of Parador, a comics artist named Celestino Villarosa tries to get his career off the ground. While Igort gives us all sorts of information and backstory on Celestino and his sister (with whom he lives), there's a lot more distance when it comes to Hiroshi.

What makes this story remarkable is Igort's visual approach. He combines an almost clear-line style and narrative clarity with aggressively experimental page composition and elements of magical realism. There's an amazing page where Hiroshi's grandmother is laying on her back, telling him about a sacred Baobab tree. The tree was in Africa (the third continent of influence in the series) and she saw it as a child, and it was said to have been the home of a monkey god. As she's laying down, telling her story, we see a Baobab seemingly growing out of her, almost oppressively. That sense of impending doom is thick in this part of the story, and we get hints that a typhoon is coming as one character wishes for an earthquake to "swallow up everything".

Thus far, we've seen much more of Celestino. This storyline seems to be as much about Igort's own relationship with comics and interest in their power, mystery and history as it is about a narrative. The first issue introduces us to Morvo, a sort of Winsor McCay-type strip about a man who swallowed up the night. The second issue follows Celestino's career further as he interacts with other artists, searches for inspiration and finally achieves it when he's struck by a fever. The second half of the issue concerns his sister and a horrible hacking cough that no one could cure. Bringing in a traditional healer, she induces a trance that was depicted in a series of pages that can only be described as a jaw-dropping tour-de-force. Igort's sensational imagery is marked by heavy blacks, dense cross-hatching and blues both oppressive and comforting. She saw a strange man called Wolla Walla, and while she was not cured, she did become obsessed with his existence. As this issue ended, she was signaling him in the night sky, wishing to be taken away.

BAOBAB functions as a sort of middle ground for the Ignatz line. It straddles the clear-line approach and everyday subject matter of the likes of Gipi & Kevin Huizenga and the more abstract comics of Anders Nilsen & Lorenzo Mattotti. It's work that's both personal and experimental, a melding of interests in a sweeping, mysterious and ambitious narrative. When this is eventually collected and published, it could make a huge splash in the publishing world. Until that time, we as readers will be lucky enough to enjoy the extra decorative elements in each beautiful issue.

BABEL

David B. is one of my favorite artists in the world, and his EPILEPTIC is one of the greatest comics ever created. So it comes to no surprise that his BABEL would be right up my alley. The first issue was actually published by Drawn & Quarterly before there was an Ignatz line, and the quality of the publication is of a slightly lesser quality. Still, it's considered to be issue zero of the line. This series is a continuation and sequel of sorts to that comic, which is a memoir of the artist's youth and his relationship with his family. In particular, it concerns his brother, who suffers from epilepsy. The book is about how children cope with fear and uncertainty, and vividly crosses the fuzzy line between fantasy and reality in how children see the world.

BABEL is a sort of clearing-house for memories, dreams, histories, ideas and images. David B.'s family informs most of his work, and so it's no surprise that he starts the book with a childhood dream of his ancestors who gave him secret knowledge of the King of the World. This is a being that played many roles in his dream life, but most of them revolved around power. The power to control one's environment, to control one's surroundings, especially for a child whose brother was suffering so much, was a natural feeling. This sense of trying to fight to gain this power is what fueled his fantasies and obsession with warfare that informed his dreams and comics and this series in particular. Conflicts in Biafra, Papua New Guinea and Algeria drew in the young artist, each one providing what seemed to be a series of clues in deciphering the mysteries of his family's struggle. The second issue of BABEL ends as David B starts discussing Algeria, a topic on the tongues of every adult he knew, something that was a matter of national anxiety in France. Most of the stories here are done in shades of red and pink, but the chapter on Algeria is in stark black & white. There's a sense that for the first time, the young David B. is beginning to comprehend what war truly means for those that fight it, and is perhaps becoming uncomfortable with it as a metaphor for gaining control of his world.

I would urge readers to read EPILEPTIC before starting BABEL, though David B. makes sure that it isn't absolutely necessary. Still, the former work will help the reader fully enjoy David B.'s stylized figure-work, bizarre decorative touches, eccentric composition and odd flights of fancy. There's no one quite like David B. working in comics today, especially in the field of memoir/autobiography. For him, dreams and real life combine to form something altogether new, and the reader is rewarded with a peek into a dense imagination.

REFLECTIONS

Marco Corona's series is the first in the Ignatz line to reach a conclusion, and this story proved to be haunting, sad and beautiful. The title is a play on several different approaches to reflections, both literal and metaphorical. The story revolves around a brother and sister over vast periods of time. The scene that ties each of the three issues together is a dream that the girl has had, in one form or another, for her entire life: walking through a huge house with a crystal chandelier, and being led to a mirror by her eccentric mother and being asked what she saw. Her brother is in a hospital, suffering from some mysterious malady. The girl is more jealous of the attention he receives than concerned about his health, and this triggers a fit of rebellion: walking under a bridge to bum cigarettes. This leads to a traumatic event that ripples through the rest of her life.

We see the girl, Miranda, as a youngster and as an old woman, living alone with only the company of cats. In the first issue, the art is in black & white--feverish and sketchy, with all sorts of loose cross-hatching. Miranda tells her story but it isn't the whole story in this issue--as she hints when she says, "We're a family of liars. But when I tell people no one believes me." That bit of narration presages her traumatic assault, one that left her mere feet from her future, which she always thought would be "translucent and incandescent". She doesn't reach it.

Miranda's brother Riccardo is obsessed with pirates, fancying himself the captain of a ship. The second issue flips the narrative from what seems to be his perspective--but it slowly turns out to be a different version of Miranda's story, just told on a pirate ship. This issue masterfully uses a blue wash to depict ghostly flickerings of light and an air of menace, with only flashbacks in a more "realistic" black & white scribble. The third issue is also in that same blue wash, but this time it's back in the real world. Riccardo gets better but the experience of his illness changes him, and he flees into his world of fantasy by doing nothing but traveling the world as an adult. Corona cleverly blurs the line between fantasy and reality by suggesting certain elements of the pirate story (like the gods and shamans of an island the mariners discover) influenced Riccardo's recovery. The blue light of the ocean blurs into a dream, which blurs into nightmare, which coalesces back in the waking world--but all is not well, even as "everything starts somewhere". REFLECTIONS is simply masterful, subtly told and well worth several readings. It needs to be approached from multiple angles as the reader and Miranda unpacks her memories, stories and deceptions. Getting at the core of her pain is evasive, both for the reader and the character, and it's even more evasive for Riccardo, who is really only a reflection of Miranda's memory. Of all the stories in the Ignatz line published to date, this one packs the most emotional power.

NEW TALES OF OLD PALOMAR

In many ways, this is the warmest and most straightforward of the Ignatz books, though these comics by Gilbert Hernandez work on many levels. For readers unfamiliar with his other comics, they are low-key character studies set in a small Latin American town. For those long-time fans of Beto's work, NEW TALES is not just a nostalgia ride, but rather an exploration of youth, innocence and the factors that lead to corruption. In particular, Hernandez focuses on characters who died very early on in his grand Palomar epic, revealing hidden depths and plumbing secrets from the past. As always, it's the children who interest him the most, and Beto masterfully manages to simultaneously explore beginnings and endings.

The subtitle of these issues is "The Children of Palomar" and Beto turns back the clock to shortly after Chelo became sheriff of the town. While we catch glimpses of the Israel-Heraclio-Satch-Pipo-Vicente crew as well as Luba in her prime, the focus in this issue is a lighthearted search for two speed demons who are stealing everyone's food in the small village of Palomar. After Pipo chases them down and their identity is revealed (a pleasant surprise for long-time readers), the first act ends, with meaningful words and glances exchanged between certain characters that would echo in later years. In particular, there's a stunning 3-panel page where Heraclio says something to his future wife Carmen that makes her realize his feelings for her. In one panel, it's all white, with the exception of a small Carmen in the upper left-hand corner and Heraclio in the lower right hand corner, walking away. For that moment, and for the first time, they're the only people in the world. The third panel sees Carmen walking away from us in a densely cross-hatched panel, a slight jaunt to her step. The second act highlights the folly of the town's adults (and men in particular), as a near-tragedy is averted. The rewards in this comic are small and comforting, as Beto skillfully and quickly builds an entire world that draws in readers.

The second issue takes a weird left turn that is more typical of his recent work. If the first issue seemed nostalgic, it was only to set up what he was really doing in these comics. The second issue goes back further in time to explore characters like Manuel, Soledad, and Pintor--all of whom died very early in the actual LOVE AND ROCKETS series. It also examines Gato, a key character in the first issue, as we see his childhood and the qualities that made him such a complex man. He was both bullied by older, cooler kids that he wanted to hang out with (earning the sympathy of the reader) and displayed his penchant for bullying and pettiness. Pintor and his generation of pals have Gato up a tree, humiliating him as he begs to be part of their gang. Gato and Pintor wind up on the wrong side of a chasm, and then things get weird. The unexplained, surreal elements often present in Beto's work take center stage here, but the story is really about the connection between past, present and the end of one's life. A younger Chelo winds up saving the day but only winds up creating another mystery afterwards. All of the boys in the story learn how they will die (things long-time readers already knew), but we don't know what Chelo saw.

I would guess that the last issue of NEW TALES will go even further into the past, perhaps into Chelo's childhood. Hernandez just finished the future Palomar stories in recent issues of LOVE AND ROCKETS, so it's interesting to see him go back and shed new light on old characters. His art has never looked better, adding a decorative aspect to his pages that wasn't always a staple of his work. As always, his character design is varied, rich and eccentric. It's fitting that Gilbert's coda to his masterwork should appear in a line devoted to featuring some of the best that comics has to offer on two continents.

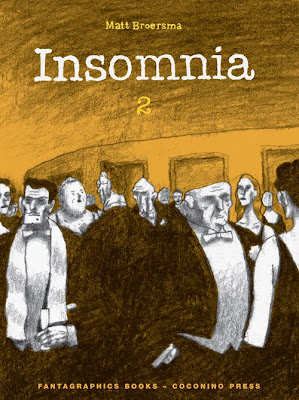

INSOMNIA

British artist Matt Broersma is creating a series that sweeps across the dusty and forgotten streets of America, telling quiet little stories about people either trying to outrun or confront their pasts. The tone is different from Gipi's stories. Apart from the air of menace that pervades those stories, Gipi places the blame for his character's troubled lives squarely on their own shoulders, while in Broersma's world, many of his characters are victims of circumstance. Broersma's visual approach is a bit like Gipi's--scratchy but expressive art, with unusual stylizations. However, Broersma is more whimsical and cartoony, and isn't afraid to insert absurd elements into his otherwise straightforward character studies. These stories are Altmanesque in that they follow seemingly unconnected people around. It's less about plot than it is about an emotional narrative, journeys being taken with indeterminate endings.

The first issue starts with a poker game being played by elegantly-dressed skull-faced men. One is a dapper playboy-type, another a priest, another a cowboy. It's unclear if they're grim reapers or what connection they have to the other stories, but it's clear that their presence sets a tone. The series is called Insomnia, and the stories revolve around sleepless journeys and the odd things that we encounter on them. We see a man running from the police heading for the Mexican border, passing by some prisoners thinking about their fondest memories--and the fugitive coincidentally drives past one of the prisoners who is talking about him. As it turns out, he's a bartender named Marco, and he's dodging serious trouble. After he seemingly commits suicide, he passes by the skeleton-men (now playing as a mariachi band!) and is fished out by someone he owed money to. Marco is haunted by a lost connection (a running theme in the series), but by the end, he either comes to terms with his loss or stops caring about it--either way, he finally gets to sleep, ignoring a ringing telephone.

The first issue is in a blue wash, reflecting the moodiness of the story. The second issue is in a dark yellow wash. This story is all about tricks of the eye and memory, a weird fever-dream taking place during winter in the city. There are two storylines that cross here: one is about an elderly man desperate to connect to a woman from his distant past, and the second is about a woman looking to improve her standing in life and fantasizing about what that sort of life would be like. Both characters are forced to confront their desires and realize that continuing to obsess over them would be a dead end. Instead, both take rather dramatic means to end their obsessions--the man finds a way to destroy his memory, and the woman selects a man who isn't rich. In this story, the difference between dreams and obsessions is a thin one, and both our protagonists learn they have to jettison both to survive. Insomnia's pleasures are quieter and more subtle than some of the other books in the Ignatz line, but no less rich. There will be one more issue in the series, and it's the single issue I'm looking forward to more than any other in the line.

NIGER

This lush, vibrant forest-creature story fits into the Ignatz line by being primarily concerned with mysteries. Italian artist Leila Marzocchi uses deep reds, browns and pinks to create an intriguing atmosphere in the first issue, as we are introduced to the odd creature named Dolly by the birds who chose to protect her. The second issue's use of color is even more imaginative, as Marzocchi breaks out an intense burnt orange for certain snow sequences and Dolly's attempts at eating. NIGER is a series that's pure fantasy and world-building, slowly building up sub-plots as it introduces us to its huge cast of characters. Marzocchi's art is dense, with a look that varies between thick cross-hatching and a sort of woodcut style. She balances that through her use of color, adding clarity and brightness to the story.

While the characters are unusual, the story has a familiar feel, with echoes of Walt Kelly, Jeff Smith and even A.A. Milne in terms of the magical woods being inhabited by intelligent animals and unique beings. There are odd religious touches as well, as a giant Hand of Fatima issues a fatwa to protect Dolly. What kind of creature Dolly is a central mystery of the series. We are privy to her thoughts in the first issue, but even that information doesn't reveal much to the reader. The birds are the stars of the series so far, propelling the narrative and adding comic relief.

Marzocchi's composition, character design and use of light & color are all imaginative and enormously clever. The book's concerns don't interest me as much as some of the other Ignatz books, but it's perhaps the best example of pure entertainment in the Ignatz line. I have a sense that it will take a few more issues to get a real sense of where this story is going and what depths it might plumb, but this series certainly gets my vote as the most immediately accessible Ignatz book for a general reader.

INTERIORAE

Gabriella Giandelli's series is a sort of cross between Rear Window and odd genre fantasy. We follow a magical white rabbit around as he observes the inhabitants of a particular apartment building, collecting their experiences and eventually their dreams for his master, a dark creature who lives in the basement. The creature is not expressly malevolent, but seems to serve a purpose in feeding on the dreams of humans--freeing them of their nightmares.

There's a real verisimilitude in the way she depicts the everyday life of her characters, both young and old. Secrets, lies and mysteries all abound here, but the device of an omniscient observer renders them petty and silly. The book's iciest character, an executive who's fooling around with a woman who herself is involved in an affair, loves to spy on others with his telescope, desperate to break free of the boredom in his life.

Giandelli's art is lush and rich, though she offsets that quality with a flat color wash (brown in the first issue, green in the second) for the flatness of everyday routine that she depicts. The flatness of scene matches the flatness of affect of many of the protagonists. Many of them are profoundly lonely and alienated, and deal with it in different ways: drugs, affairs, screaming arguments, and fantasies. The one person who seems to transcend this treadmill is an old woman who is starting to flash back to her childhood. She reveals to her daughter that she has one last task, but what that is hasn't been revealed.

The pace of these comics is rather languid, but Giandelli's pages are beautiful enough to hold one's eye, and the tension between fantasy and reality is thick enough to keep the reader guessing. It's that tension that makes the series worth reading, because either element alone would make for a rather routine read. The greater mystery of the fantasy element of the series gives the book's voyeuristic quality some depth. That fantasy element is used sparingly and mostly as a framing device, allowing the book to unfold as a series of character studies. While not the most profound or revelatory book of the Ignatz line, there's still a stirring beauty to be found here. It'll be interesting to see how the story continues to unfold and what additional depths we might find as readers.

DELPHINE

Richard Sala is the thinking man's horror artist, using his playful, cartoony art style to generate white-knuckle suspense. Sala is adept at making the audience laugh one moment and cringe the next, heightening suspense by making the familiar seem creepy and the absurd disturbing. DELPHINE has been described as a modern-day retelling of Snow White, and there are certainly some familiar elements: crones, apples, dwarves, etc. However, this story is simultaneously darker and wackier than Snow White--no surprise from Sala.

DELPHINE fits in well with the Ignatz line. It's all about mysteries and secrets, just like many of the other books. It's just that the secrets are malevolent and the mysteries a matter of life-and-death. Our hero is a typical Sala protagonist--a young man who's looking for someone and winds up in a sinister town with weird denizens. The "someone" in this case is the series' namesake, Delphine. Trying to track her down to a specific address, the first two issues are a comedy of terrors, as our hero goes from one escapade to another. This book may be the most pure fun of the Ignatz line, and I expect it to become even more gripping as the series proceeds.

GANGES

I've been a fan of Kevin Huizenga since he was doing his minicomic SUPERMONSTER, and it's been enjoyable seeing him hone his skills as he quietly produced comic after comic grappling with issues of time, theology, mortality and phenomenology. Continuing the "adventures" of Glenn Ganges and his wife Wendy, Huizenga adds a few additional layers to his usual storytelling style, resulting in a surprisingly emotional experience.

The first story, "Time Travelling", is typical Huizenga in terms of its formal trickery and obsession with temporal concerns. We see schematics, nested and embedded panels and other such tricks as Glenn conflates the familiar with the eternal. It's a nice introduction for new readers as to what Huizenga's all about, but it's more of the same for long-time readers. However, in the next story ("The Litterer"), Huizenga unexpectedly plays this kind of reverie for laughs. Indignant at seeing a teenager littering on the street, Glenn concocts an elaborate set of scenarios where the litterer's disregard for the environment and sense of entitlement propels him to an increasingly over-the-top chain of events: the litterer (still wearing his bicycle helmet!) is swept into public office, brutalizes the populace, starts wars, worships Satan, and kills women with his bare hands. The best image is him sitting atop an elephant as a conquered city is in flames at his feet. Glenn snaps out of it, and Wendy asks him the obvious question: "Did you pick up the litter?" The final punchline perfectly captures Glenn's self-absorption.

The last story, "Bed", packs a powerful emotional wallop. After spending a quiet evening with Wendy (in a fantastic moment-by-moment, beat-by-beat story), Glenn joins his already-sleeping wife in bed. Watching her sleep, he's overcome by the historical weight of lovers throughout history watching their mates. Huizenga then gives us another tour-de-force of page & panel design, but this time they pack so much emotional weight, evoking the power of connection between people and what happens when that bond is threatened. Huizenga adroitly moves this beyond mere sentiment by acknowledging through Glenn that this is a common, even cliched, thing to feel--but that feeling is no less real. The muted blue-green tint that Huizenga employs gives the comic a sleepy, thoughtful feel. His figures are simple but elegant, the perfect match for his often aggressive formal experimentation. It's interesting to see Huizenga flex some different muscles as a cartoonist in GANGES, pointing to his continued evolution as one of the most important young cartoonists working today. One senses that as innovative and interesting as his comics are now, his best work is yet to come.

SAMMY THE MOUSE

Zak Sally instantly become a favorite of mine the first time I read RECIDIVIST. Those tales of despair and the grotesque were enormously powerful, even visceral, in their impact. He takes a slightly different turn in SAMMY, though his bleakly cynical point of view is still intact. This is clearly a series whose episodic nature prohibits me from fully examining its themes until more issues are published, but there's a rollicking earthiness to the proceedings that immediately struck me as a reader. We're introduced to the title character and a drunken acquaintance who bangs down his door and demands booze. They later meet up with a friend called Puppy Boy, who suffers from seizures, and are accosted by a strange skull-faced man who fires a gun into the air. Sammy and Puppy later wander off, with Puppy making noises about some strange project he's working on. There's a bit of an underground feeling to this comic, with echoes of Crumb and Deitch by way of Tony Millionaire. At the same time, the story has the feel of something autobiographical, as though Sally had experienced this kind of night on more than one occasion. The slightly ragged nature of Sally's outwork is a nice complement to his exaggerated & vivid character design and the unusual two-tone colors. Best of all, Sally generates some laughs with his outsized characters. Even though one senses that all is not right in Sammy's world, he still continues to plow through and take on the ridiculousness of his life. He tried avoiding it at the beginning of the book, but it's clear that circumstance wasn't going to let him avoid adventure. I have a feeling that this series could go on for awhile, but it's just getting warmed up at the moment.

THE END

Anders Nilsen's comic is painful to read. It's a follow-up of sorts to DON'T GO WHERE I CAN'T FOLLOW, a mixed-media comic about the death of his girlfriend due to cancer. Having read that is not important to understanding THE END, however. He sets the story up at the very beginning and asks the audience to imagine a couple who have a good life together and an expectation of how things will proceed in their life, and then to suddenly have not just that life taken away, but our understanding of reality and meaning as well. It's both intensely personal and a story whose core can be understood by anyone who's ever experienced loss. Most stories that deal with loss or disaster tend to have a built-in distancing by the author, even if it's an autobiographical account. There's a sense that some kind of sense needs to be made of tragedy, some kind of closure, some kind of meaning attached to tragedy--"everything happens for a reason."

In THE END, there are no filters, no answers, no pat resolution. The story alternates between an ultra-stripped down, sketchy style where Nilsen just goes on long rants, and quieter & more detailed personal anecdotes. The most devastating of those is a dark bit called "Since You've Been Gone I Can Do Whatever I Want, All The Time", which consists of the main character either crying during his daily routine or trying to keep it together in public. The first caption is "Me Crying While Doing The Dishes" and it goes on from there, as he tries to slowly live his life and process his grief.

From there, there's an extended sequence where he uses mathematical formulae to try and make sense of a life that's fallen apart, that's lost meaning. The stick figure that Nilsen uses morphs into a maze, a computer-chip pattern, and then a dot-grid. He's looking for patterns to rebuild himself, and there's a sense that this experience, this pain, will build into something constructive. He'd like to believe that, but can't feel it: "If two can be made one and then one can be suddenly made half...well then a half might as well be zero...you might not even care what x is anymore it might not be anything at all. Just a bunch of bullshit. Just a bunch of dirt."

THE END is a staggering, bracing read, totally unlike the rest of the Ignatz line. The decorative touches that mark the the rest of the line are absent, and it's far away from a conventional narrative. But it's still about a mystery, the mystery of meaning. It's the best kind of autobiography, eschewing any sentimental elements and managing to completely free itself of the narrative template that's often overlaid on anecdotal autobiography as a way of making it easier to follow. For Nilsen, there is no story, there is no narrative--his narrative has fallen apart, and he's trying to figure out how to put it back together, if he even can. This comic is a testament to Igort's willingness to edit a truly broad range of comics under one line.

GROTESQUE

The first issue of this series was quite a wild ride. Sergio Ponchione has absorbed a lot of different influences and has become a skilled style mimic who can flip through several different approaches in the span of a single page. The press materials compared his surreal imagery to Roger Langridge, and with his reliance on thick, bold but clear black lines, it's not a bad comparison. But there's other stuff in there as well: a European clear-line style, Segar-esque character design, bits of Crumb, hints of Deitch (both Gene's animation and Kim's comics), a smidgen even of eccentric mainstream artist Richard Case. In terms of pure black-and-white eye candy, this is my favorite book in the Ignatz line to simply look at.

This book is about secrets, mysteries and the hope for renewal in the form of a quest. Three different men are drawn to three different strange islands at three different times--but all for similar reasons. They are unhappy with their lives and feel a gnawing need for change, for something different. One man is an explorer with a key given to him by a wizard who's looking for the island by boat. Another man has a bookmark that's affecting the books he reads: the characters he reads about start interacting with each other independently on an island, and he can hear their thoughts as they start to mix with his. A third man in the future is followed by an island that's floating around and following him. Finally confronting it, he knows that a magical glass eye that he's holding is the key to solving his problem. The central figure here is a shadowy and possibly sinister man named Mr. O'Blique, who created all three islands and has drawn in all three men.

Each of the three stories comes to a head as Ponchione weaves different side characters in and out of each man's life. The result is a pleasant mishmash of influences that have a familiar feel yet are wholly original. It's almost a meta-story in some ways for me as a reader; the story about a story that takes on a life of its own made me feel as though I had read that story myself in the past. There's a feeling that's evoked from reading it that's drawn from the periphery of my memory, almost like deja vu'. The book is quite enjoyable on a literal level, but it'll be interesting to see if it becomes a bit deeper on a metaphorical level.

CHIMERA

Lorenzo Mattotti, one of the most popular cartoonists in Europe, delivers a beautiful stream-of-consciousness bit of fantasy. Starting from a loose, sparse and sketchy series of pages, this book grows more intense and dense as the pages turn. Its conceit is a thinker sitting beneath a tree, and passerby thinking that he must have a secret that can't be discerned. As two children nestle underneath the tree, we see a fantastic world unfold in front of them, a bit reminiscent of Ben Catmull's recent comic Monster Parade. Gigantic, distorted humanoid figures cavort in the sky, have sex, prey on people and each other. The book goes from that initial clear line to a thick series of scribbles and cross-hatches, adding tension. Mattotti is a master of using blacks and negative space to create movement, especially on the pages where a monstrous bird-like creature preys on gigantic black rabbits. The most impressive sequence in the book comes at the end, when we take a step into an impenetrable forest and follow a traveler on foot. Mattotti uses swirling black brushstrokes and creates just enough light to allow the eye to follow the action, as the reader is swept along in the darkness. There's not a lot to say about the story or its themes; it's simply a comic that a reader must allow to wash over oneself so as to drink in the visuals. There's not a conventional narrative to speak of here, but any fan of great cartooning owes it to themselves to seek out this comic.

CALVARIO HILLS

This is the only series in the line that's an explicitly political work. The Spaniard Marti reimagines America in an over-the-top, often ham-fisted social & political satire. His figure work is thick and rubbery, with the kind of exaggerated expressions and dense blacks that are not unfamiliar in some American underground work. Essentially, Marti boils down the worst of America into one city called Calvario Hills, where African-American gangs clash with right-wing NRA members who are also members of racial purity movements. There's not a moment that goes by that isn't ridiculously exaggerated, like the racist gun-shop owner and grenade collector who puts landmines in his yard to "protect" his pregnant wife from the assorted minorities in the neighborhood and winds up blowing up his dog. His wife threatens to blow them up with a grenade, so he shoots her and makes up a story about a black man killing her. From there, a black drug dealer is making plans from prison to install a black mayor (a thinly-veiled Marion Barry figure) in order to remove guns from the street. The NRA opposed this and set up a Barry-style sting where he got caught smoking crack. The story, wacky as it is, feels like any internet conspiracy theory. The story is slick in the worst of ways--there's nothing for a reader to grab onto at a human, emotional or visual level. Politically, Marti is preaching to the choir here--I certainly don't object to the story on that basis, but it does feel like so much empty rhetoric.

The second story is even wackier, depicting the further adventures of Marti's famed character Cabbie. This time around, a disgraced European president is on the lam after being convicted of corruption, and Cabbie is hired to get him out of the country. As the story proceeds, he gets mixed up with a corrupt cardinal who's part of a vast conspiracy to get him installed as the next pope. That cardinal has mind-control powers and is doing strange things with a fetus as the president and Cabbie walk in, and the president talks him into letting him stand in his luggage to make his getaway. They run into a wacky gay-pride parade ("Gay Sabbath") where the cardinal is dragged out and the president gets thrown in a garbage truck in his cross-shaped trunk. It all reads like a revenge fantasy of Marti's, but the problem here is that the imagery doesn't go far enough. It's more silly than shocking, and while Marti is clearly playing the whole issue for laughs, it mostly falls flat. Satire is a delicate thing, and while Marti pulling out all the stops at once is admirable in some ways, it makes for a jarring read. If the intent was humor through transgression, then Marti didn't go far enough in that direction to sustain an entire issue. As political satire, the hits it scores are obvious and telegraphed, and there aren't a lot of laughs to be found. The series is all about lies and how the powerful use them to exploit others--but it just didn't seem like news to me. It is remarkable that for all the varied styles and points of view in the Ignatz line, Marti's was the only one that fell flat. I can certainly see how this series might appeal to some, and there's no question that his visual approach is a perfect match for his subject matter.

CONCLUSION

If these books had come out a decade ago, they would have been the talk of the comics world. In this current golden age of remarkable original graphic novels and several generations of cartoonists producing great work all at once, the Ignatz line doesn't get quite the same level of acclaim despite its excellence. Part of that is that these are Comic Books, rather than "graphic novels", and Comic Books are simply not in vogue. As the series start to get collected in graphic novel form, they will likely draw a lot more attention from the comics and popular press. Until that time, those readers who are tuned into the line will get to experience the thrill of comics-as-periodical once again, this time uniformly created by comics' cream of the crop on two continents and given the highest possible production values

No comments:

Post a Comment