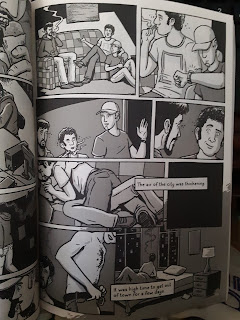

Mike King, currently using the pen name Michael Sweater, does what I sometimes refer to as "pop-punk" comics. These are artists who very much live a DIY, punk ethos and do frequently sweet, punk-themed comics, often revolving around a fantasy theme. His collection of comics from 2013, Lion's Teeth, puts all of his influences on display. Graffiti art, tattoo art, manga, fantasy comics, autobio comics, and more all are all there, blended in a confident and stylized line that's the clear result of drawing a lot of pages. The five issues of Lion's Teeth add up to nearly five hundred pages, including some work drawn in 2011. The cumulative effect of all of this is closer to looking at an intensely worked-over sketchbook than a coherent anthology series, but that rawness is part of the appeal.

The best strips are the ones featuring Dave, the wizard school student. Armless due to a curse, he loves magic but claims to hate everything else: the perfect, disaffected protagonist. Of course, that's all a pose, as he has a strong friendship with his anthropomorphic owl friend Argyle and a frenemy relationship with Richard, the snake who lives in the tree in his backyard. King's character design is top-notch, but the barrel-chested Dave is particularly inspired. Dave and friends are just as likely to go on a quest for death-summoning skull as they are to go out and eat the best pizza in the world, and that's part of the charm of the strip. Death himself is just a guy who has to go out and do a job, and it's frequently an annoying one. His adventures run parallel to Dave's until he is finally summoned, and their conversation is a surprisingly poignant one. I'd love to see more of these characters, especially because they provide such an interesting alternative to the all-too-familiar "wizard school" trope.

There are a lot of interstitial pages here devoted to King's graffiti/tattoo art designs. Here, he uses a big, bold line with stark black/white contrasts. It's different from the rattier, looser line of his comics, while also use zip-a-tone and gray-scale effects to fill in negative space in order to add weight to the page. There are also the "Clyde" comics, which are done in big, chunky lines on the back of old priority mail envelopes. There's also his older "Make Me" comics from 2011, which are more random bits of humor. There's one running bit where a human refuses food to an animal or threatens to hurt them, and then a huge boxer shows up to beat the human to a pulp. King's comic timing is sharp, and his use of callbacks like this is smoothly developed. There are also comics featuring little punk kids being schooled in how to be properly punk by adults. The other major comics in these collections are autobiographical, where he draws himself as an anthropomorphic cat and his girlfriend (now wife) Benji as an anthropomorphic mouse. King can actually get pretty raw and real with regard to his mental state in these strips--both in the comics about himself and in the Dave comics in particular. That mix of well-developed craft and a willingness to try anything is a hallmark of his work, which has continued in the books he's done with Silver Sprocket.

This is the blog of comics critic Rob Clough. I have writings elsewhere at SOLRAD.co, TCJ.com and a bunch more. I read and review everything sent to me eventually, especially minicomics. My address is: Rob Clough 881 Martin Luther King Junior King Blvd Apt 10 i Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Tuesday, December 31, 2019

Monday, December 30, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #30: Andy Warner

Andy Warner, along with Josh Kramer, Eleri Mai Harris, Dan Nott, Dan Archer, and a few others, make up a group of CCS grads whose primary interest is in comics journalism. Unsurprisingly, Warner has been a longtime mainstay of The Nib, and he's one of their best contributors. His minicomic, Eruption, is a good example of his Nib work. It's meticulously-researched, thought-provoking, and provides a human angle on everything. This is about the eruption of Mt. Kilauea in Hawai'i a few years back. In his clear, rich detailed drawing style, he gives the reader a sense of what it was like when the volcano erupted, but he also provides information as to the implications and repercussions of the event, both geologically and economically.

On the other hand, Spring Rain, his memoir of being in Beirut in 2005 when a revolution was breaking out, is sprawling, self-indulgent, messy, and raw. As he discusses in the book, he's told a lot of stories about Beirut in the course of his comics career, but he always left out all of the significant personal details. This book integrates a significant mental breakdown he experienced, the fraught relationships he was dealing with, and the extremely tenuous political situation that exploded around him. All at the age of 21.

Writing this kind of book was an all or nothing proposition. After years of holding back, Warner had to discuss everything, no matter how embarrassing or painful it was. It's clear that he was as honest as he possibly could be in telling this story, because he does not make himself a sympathetic character. Indeed, his time in Beirut could be described as a continuous series of bad decisions, starting with breaking up with his girlfriend in America prior to the trip, for no reason other than being apart. He regretted it immediately and talked to her via email when he could, but it was obvious that he had unfinished business there and it gave him a baseline level of misery.

That was balanced against Warner making a number of remarkable friends. Some were natives of Lebanon, while others were from the US like he was. Living abroad, it wasn't surprising that the isolation of this experience would lead to him making such fast friends, and it was clear that they knew that he needed them. They encouraged him to go out instead of stewing alone in his depression. A major subplot of his story was that many of these friends were gay men, which puzzled a few since Warner was ostensibly straight.

That in itself was a key element of the book: Warner coming to terms with his own sexuality and how that related to trauma. An incident from high school where a guy he wanted to be friends with grabbed Warner's crotch against his will confused and traumatized him. That led him to stop trying in a class, and one day the teacher punished him by laying him down on the floor and telling him to hump it. Shame, rage, humiliation--all bottled up. On top of all that, Warner's family had a history of mental illness. All of that subsumed trauma combined with genetic tendencies made Warner a ticking time bomb.

Throw all of that on top of a genuine political uprising that alternated moments of hope and solidarity for the Lebanese with cynical machinations by Syria, the PLO, and America, and you had an almost absurd outward manifestation of the roiling paranoia and despair that Warner felt. Indeed, almost every one of his friends had their own inner struggles. One gay friend took a bunch of pills to kill himself because he knew his parents would never approve of him. As the world became more uncertain, Warner's relationships with his friends grew closer but also more unstable. His next-door neighbor and close friend came on to him despite him having a boyfriend, but Warner agreed to hook up with him several times. He had sex a few times with one of his female friends and both tried to pretend it didn't mean anything until it did. When he tried to get her to hook up with someone else at a party, it was an act that demeaned and hurt her. Of course, the group throwing drugs into the equation did little to calm things down. All that did was accelerate the madness, matching the madness around them.

Warner's own depiction of his breakdown and near-suicide attempt is harrowing. It was unsparing and used the full range of his considerable skill as a draftsman. For weeks, he had heard voices. He had seen threatening faces. The whispers grew louder on that night, and then eventually they passed. It is no coincidence that he had decided to do a story about his high school experience, releasing that trauma a little. The importance of art in Warner's life is one of the big emphases in this book; he never comes out and says it, but it's obvious that art saved his life. It's also clear that writing this book is something he had to do. Everything that happened was too big to wrap his mind around, but he couldn't help but try to do it anyway. Warner tries to give the reader a sense of Beirut and its history, what its people are like, and what it's like to be a student abroad. Then he tries to do this as a completely unreliable narrator in a volatile political situation while on drugs. It never quite coheres, but neither did his experiences. A bunch of horrible and beautiful stuff happened to Warner. He made a number of bad decisions and hurt some people's feelings as a result. He made it through as best as he could, and came clean with regard to trauma and mental illness through his art. If nothing else, he paid a debt to himself and others by being open about what happened to him in Beirut, bridging the gap between journalism and memoir in a graphic, compelling, and expansive manner.

On the other hand, Spring Rain, his memoir of being in Beirut in 2005 when a revolution was breaking out, is sprawling, self-indulgent, messy, and raw. As he discusses in the book, he's told a lot of stories about Beirut in the course of his comics career, but he always left out all of the significant personal details. This book integrates a significant mental breakdown he experienced, the fraught relationships he was dealing with, and the extremely tenuous political situation that exploded around him. All at the age of 21.

Writing this kind of book was an all or nothing proposition. After years of holding back, Warner had to discuss everything, no matter how embarrassing or painful it was. It's clear that he was as honest as he possibly could be in telling this story, because he does not make himself a sympathetic character. Indeed, his time in Beirut could be described as a continuous series of bad decisions, starting with breaking up with his girlfriend in America prior to the trip, for no reason other than being apart. He regretted it immediately and talked to her via email when he could, but it was obvious that he had unfinished business there and it gave him a baseline level of misery.

That was balanced against Warner making a number of remarkable friends. Some were natives of Lebanon, while others were from the US like he was. Living abroad, it wasn't surprising that the isolation of this experience would lead to him making such fast friends, and it was clear that they knew that he needed them. They encouraged him to go out instead of stewing alone in his depression. A major subplot of his story was that many of these friends were gay men, which puzzled a few since Warner was ostensibly straight.

That in itself was a key element of the book: Warner coming to terms with his own sexuality and how that related to trauma. An incident from high school where a guy he wanted to be friends with grabbed Warner's crotch against his will confused and traumatized him. That led him to stop trying in a class, and one day the teacher punished him by laying him down on the floor and telling him to hump it. Shame, rage, humiliation--all bottled up. On top of all that, Warner's family had a history of mental illness. All of that subsumed trauma combined with genetic tendencies made Warner a ticking time bomb.

Throw all of that on top of a genuine political uprising that alternated moments of hope and solidarity for the Lebanese with cynical machinations by Syria, the PLO, and America, and you had an almost absurd outward manifestation of the roiling paranoia and despair that Warner felt. Indeed, almost every one of his friends had their own inner struggles. One gay friend took a bunch of pills to kill himself because he knew his parents would never approve of him. As the world became more uncertain, Warner's relationships with his friends grew closer but also more unstable. His next-door neighbor and close friend came on to him despite him having a boyfriend, but Warner agreed to hook up with him several times. He had sex a few times with one of his female friends and both tried to pretend it didn't mean anything until it did. When he tried to get her to hook up with someone else at a party, it was an act that demeaned and hurt her. Of course, the group throwing drugs into the equation did little to calm things down. All that did was accelerate the madness, matching the madness around them.

Warner's own depiction of his breakdown and near-suicide attempt is harrowing. It was unsparing and used the full range of his considerable skill as a draftsman. For weeks, he had heard voices. He had seen threatening faces. The whispers grew louder on that night, and then eventually they passed. It is no coincidence that he had decided to do a story about his high school experience, releasing that trauma a little. The importance of art in Warner's life is one of the big emphases in this book; he never comes out and says it, but it's obvious that art saved his life. It's also clear that writing this book is something he had to do. Everything that happened was too big to wrap his mind around, but he couldn't help but try to do it anyway. Warner tries to give the reader a sense of Beirut and its history, what its people are like, and what it's like to be a student abroad. Then he tries to do this as a completely unreliable narrator in a volatile political situation while on drugs. It never quite coheres, but neither did his experiences. A bunch of horrible and beautiful stuff happened to Warner. He made a number of bad decisions and hurt some people's feelings as a result. He made it through as best as he could, and came clean with regard to trauma and mental illness through his art. If nothing else, he paid a debt to himself and others by being open about what happened to him in Beirut, bridging the gap between journalism and memoir in a graphic, compelling, and expansive manner.

Sunday, December 29, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #29: Luke Healy

Luke Healy emerged from CCS as a fully-formed cartoonist. All of his early minis are excellent and well-designed, and he's been remarkably productive since then, with three books under his belt. His most recent book, Americana, is probably the most straightforward of his books, in that it's a travel memoir that mixes text and comics. At the same time, there's something that's deeper than a simple account of hiking the Pacific Crest Trail from the Mexican border to the Canadian border. This is a story about displacement of identity at a deep level. Healy is a native of Ireland who spent a lifetime obsessing over the USA: its culture, its expansiveness, and its possibilities. He loved America, but he wasn't able to stay here for any appreciable length of time. His visa expired after a year at CCS, and he wasn't able to return until halfway through his second year. He couldn't find any jobs that would allow him to stay.

All of that led him to fixate on walking the Pacific Crest Trail--over 2,500 miles through desert, mountains, and forests. He had no experience hiking or camping at all. His "practice" was the occasional long walk on level land in Ireland. Over the course of over 300 pages, Healy details his struggles (physical and emotional) on the trail and meeting his eventual goal at the Canadian border. The way Healy writes about America and his life, in general, is a pervasive sense of something being missing--something that he could see that was just beyond his grasp. He's uncomfortable in his own skin, and that seems to have little to do with the fact that he's gay. There's a basic sense of total discomfort that's palpable in his other work by way of his characters and author persona, and a little more subdued here. After all, this version of Luke is as much an invention as in his other books, but it's the one based most closely on real events in his life.

It's also subdued because the audience is presented with all-Luke, all the time. He doesn't go out of his way to make himself likable, but he also tones down on some of the negative self-talk. Part of that is through the genuine focus on the experience of hiking the PCT. It was grueling, and he even seriously thought about quitting when he got near Los Angeles. A friend picked up him and he rested for several days, but he decided to go back to the trail again. A sticking factor halfway through was the ill health and eventual death of his grandfather; each time he thought about going home, his family encouraged him to keep hiking. He even managed to talk to his grandfather a few times, who was perfectly delighted that his grandson was hiking in America.

This book, by its very nature, is sprawling and self-indulgent. Healy has no pretensions regarding special insights into hiking, nature, America, or even himself. This is not to say that he doesn't think about and discuss all of these things, and he records it to the best of his ability. He gets across each of the bizarre environments he hikes through, from the Mojave Desert to the High Sierras, and he relays just how poorly prepared he was for all of this. He could barely set up his tent and made poor time at the beginning of the hike. The camaraderie of the trip was an interesting subplot, because it was something that he both cultivated and avoided. He usually preferred to be alone, but there were times that he wanted to share some of his experiences. That became especially true about halfway through the hike, when a mountain lion came sniffing around his tent at night. That motivated Healy to hike much faster and talk his way into camping with other folks at night.

Healy's line is simple, expressive, and surprisingly kinetic. The characters in the book are almost always moving, albeit slowly, and Healy showed a knack for depicting this movement while also providing a real sense of the environment. The pinks and blues he used as single-tone fills added just the right amount of atmosphere.

Ultimately, this is a book about emptying one's self. When one's only concern is surviving on the trail on a day-to-day basis, other things fall away. Healy was twitchy, restless, overstuffed and anxious; he implies that he was drawn to the PCT because it would beat these things out of him. The trail made him lose weight at a rapid pace, his fat reserves consumed by the relentless energy needed for the trail. There was the sort of camaraderie that comes about when people are thrown into a strenuous, isolating situation. By the end of the trail, he had not only become a proficient hiker, but the hike itself became everything. At the end, he felt mostly relief and weariness. He could finally stop. The cumulative effect was like any strenuous, meditative activity: helping Healy empty his mind and quiet it.

I don't think this book had much to do with America per se, other than simply being the setting for this trek. The quote he had at the beginning alludes to this a bit: "I'm driven by my hunger for the American experience. But also by the hope that if I gorge myself on it, I'll become sick of the taste." His PCT trek had nothing to do with the Hollywood or cultural image of America that he was so drawn to. Instead, he took on America as a beautiful, sprawling, and dangerous geographic entity. It was unsentimental, unwelcoming, and yet almost painfully beautiful at times. He let America drain his body of strength, batter him, wear him down, and finally focus. Confronting America in this way is what finally allowed him to release his fixation. It's about having no choice but to let go.

All of that led him to fixate on walking the Pacific Crest Trail--over 2,500 miles through desert, mountains, and forests. He had no experience hiking or camping at all. His "practice" was the occasional long walk on level land in Ireland. Over the course of over 300 pages, Healy details his struggles (physical and emotional) on the trail and meeting his eventual goal at the Canadian border. The way Healy writes about America and his life, in general, is a pervasive sense of something being missing--something that he could see that was just beyond his grasp. He's uncomfortable in his own skin, and that seems to have little to do with the fact that he's gay. There's a basic sense of total discomfort that's palpable in his other work by way of his characters and author persona, and a little more subdued here. After all, this version of Luke is as much an invention as in his other books, but it's the one based most closely on real events in his life.

It's also subdued because the audience is presented with all-Luke, all the time. He doesn't go out of his way to make himself likable, but he also tones down on some of the negative self-talk. Part of that is through the genuine focus on the experience of hiking the PCT. It was grueling, and he even seriously thought about quitting when he got near Los Angeles. A friend picked up him and he rested for several days, but he decided to go back to the trail again. A sticking factor halfway through was the ill health and eventual death of his grandfather; each time he thought about going home, his family encouraged him to keep hiking. He even managed to talk to his grandfather a few times, who was perfectly delighted that his grandson was hiking in America.

This book, by its very nature, is sprawling and self-indulgent. Healy has no pretensions regarding special insights into hiking, nature, America, or even himself. This is not to say that he doesn't think about and discuss all of these things, and he records it to the best of his ability. He gets across each of the bizarre environments he hikes through, from the Mojave Desert to the High Sierras, and he relays just how poorly prepared he was for all of this. He could barely set up his tent and made poor time at the beginning of the hike. The camaraderie of the trip was an interesting subplot, because it was something that he both cultivated and avoided. He usually preferred to be alone, but there were times that he wanted to share some of his experiences. That became especially true about halfway through the hike, when a mountain lion came sniffing around his tent at night. That motivated Healy to hike much faster and talk his way into camping with other folks at night.

Healy's line is simple, expressive, and surprisingly kinetic. The characters in the book are almost always moving, albeit slowly, and Healy showed a knack for depicting this movement while also providing a real sense of the environment. The pinks and blues he used as single-tone fills added just the right amount of atmosphere.

Ultimately, this is a book about emptying one's self. When one's only concern is surviving on the trail on a day-to-day basis, other things fall away. Healy was twitchy, restless, overstuffed and anxious; he implies that he was drawn to the PCT because it would beat these things out of him. The trail made him lose weight at a rapid pace, his fat reserves consumed by the relentless energy needed for the trail. There was the sort of camaraderie that comes about when people are thrown into a strenuous, isolating situation. By the end of the trail, he had not only become a proficient hiker, but the hike itself became everything. At the end, he felt mostly relief and weariness. He could finally stop. The cumulative effect was like any strenuous, meditative activity: helping Healy empty his mind and quiet it.

I don't think this book had much to do with America per se, other than simply being the setting for this trek. The quote he had at the beginning alludes to this a bit: "I'm driven by my hunger for the American experience. But also by the hope that if I gorge myself on it, I'll become sick of the taste." His PCT trek had nothing to do with the Hollywood or cultural image of America that he was so drawn to. Instead, he took on America as a beautiful, sprawling, and dangerous geographic entity. It was unsentimental, unwelcoming, and yet almost painfully beautiful at times. He let America drain his body of strength, batter him, wear him down, and finally focus. Confronting America in this way is what finally allowed him to release his fixation. It's about having no choice but to let go.

Saturday, December 28, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #28: Liam McTaggart

Liam McTaggart is a first-year CCS student with a scribbly, scratchy minimalist style. His work reminds me a little of Emma Hunsinger's (although she uses more loopy lines), and both of their comics remind me of Jules Feiffer's comics. By is a short comic depicting the heart-rending visit of a man and his elderly grandmother who has dementia. Every day is the same series of emotionally draining conversations and then a return to a hotel and anesthesizing routine until the next round of hard conversations. The next day is even more difficult, as his attempt at roleplaying his father (playing into his grandmother's delusions) is somehow even more painful. The spare drawings contrast the complexity of the emotions at work.

Picking Up Scorpions seems to be McTaggart's Aesop assignment, a variation on the old The Scorpion And The Frog story. A man asks a man for a ride through the desert, promising money. He refuses to show it first, telling the other man to trust reason--why would he doom himself? Well, when the car broke down, the man didn't have any money. It was his nature to be untrustworthy. There's a stink of desperation in this story conveyed through gesture and a minimum of lines. Their First Album is about a husband and wife who find reasons and excuses to be away from each other. While she's out walking for hours, he goes to a bar. It's not clear why they have so much trouble communicating, but her attempt to reach out at the end, after they've shared a moment together with music, is telling. This is an interesting comic because the main narrative details everything but the core emotional problems of the couple.

The Matter is a fascinating look at the end of a teenage relationship. McTaggart is aces at depicting both desperation and indifference. In this case, it was indifference on the part of a girl and desperation on the part of a guy. She had her head in the clouds as to what a relationship should be and was almost revolted by the idea of any kind of physical contact or physicality in general ("because I'm not a slut") because it went against her own personal aesthetic. For his part, he just wanted someone to love, (even if he clearly didn't understand her) but he knew what was happening and walked away. Her response was to go back to listening to pop music that drew her back to the clouds.

Simple, Stupid is the best of McTaggart's work. McTaggart has an ear for dialogue, and the verisimilitude of the conversations in this book allows him to subtly explore male toxicity and the awkwardness of desire. The story revolves around two male friends named Dean and Ted, and it's clear that Dean is in love with Ted. However, the two dance around his attraction until a drunken game of Truth or Dare, which leads to some awkward silences in the group. Later, when Dean stays over at Ted's house and strips down in front of him, he becomes embarrassed, leaves, and stops talking to his friend. Dean later enters into a romance with a girl named Sarah and approaches it with the same kind of emotional earnestness that he did with Ted, only this time he allows himself to pursue these feelings. There's a fascinating, intimate scene where McTaggart zooms in and all the reader sees are lips and a couple of other portions of the face. When Dean sees Ted at a party and Ted is clearly friendly, he realizes that his homophobia was entirely internalized. It's a rare event to read a story featuring bisexual characters, but McTaggart nails every how masculinity interferes with one's ability to express affection and attraction. McTaggart does have a few things to refine (especially his lettering), but he's found a style and tone that work well for him.

Picking Up Scorpions seems to be McTaggart's Aesop assignment, a variation on the old The Scorpion And The Frog story. A man asks a man for a ride through the desert, promising money. He refuses to show it first, telling the other man to trust reason--why would he doom himself? Well, when the car broke down, the man didn't have any money. It was his nature to be untrustworthy. There's a stink of desperation in this story conveyed through gesture and a minimum of lines. Their First Album is about a husband and wife who find reasons and excuses to be away from each other. While she's out walking for hours, he goes to a bar. It's not clear why they have so much trouble communicating, but her attempt to reach out at the end, after they've shared a moment together with music, is telling. This is an interesting comic because the main narrative details everything but the core emotional problems of the couple.

The Matter is a fascinating look at the end of a teenage relationship. McTaggart is aces at depicting both desperation and indifference. In this case, it was indifference on the part of a girl and desperation on the part of a guy. She had her head in the clouds as to what a relationship should be and was almost revolted by the idea of any kind of physical contact or physicality in general ("because I'm not a slut") because it went against her own personal aesthetic. For his part, he just wanted someone to love, (even if he clearly didn't understand her) but he knew what was happening and walked away. Her response was to go back to listening to pop music that drew her back to the clouds.

Simple, Stupid is the best of McTaggart's work. McTaggart has an ear for dialogue, and the verisimilitude of the conversations in this book allows him to subtly explore male toxicity and the awkwardness of desire. The story revolves around two male friends named Dean and Ted, and it's clear that Dean is in love with Ted. However, the two dance around his attraction until a drunken game of Truth or Dare, which leads to some awkward silences in the group. Later, when Dean stays over at Ted's house and strips down in front of him, he becomes embarrassed, leaves, and stops talking to his friend. Dean later enters into a romance with a girl named Sarah and approaches it with the same kind of emotional earnestness that he did with Ted, only this time he allows himself to pursue these feelings. There's a fascinating, intimate scene where McTaggart zooms in and all the reader sees are lips and a couple of other portions of the face. When Dean sees Ted at a party and Ted is clearly friendly, he realizes that his homophobia was entirely internalized. It's a rare event to read a story featuring bisexual characters, but McTaggart nails every how masculinity interferes with one's ability to express affection and attraction. McTaggart does have a few things to refine (especially his lettering), but he's found a style and tone that work well for him.

Friday, December 27, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #27: Emil Wilson

Emil Wilson is a CCS outlier. Not quite a trailblazer, but definitely an outlier. At 53 years old, he was already established as an art director and illustrator in San Francisco. He's married. But like a few other older cartoonists, the muse took him to White River Junction in order to learn how to tell stories. Wilson is already quite skilled and has a fully realized style. What will be interesting is to see him learn how to craft narratives and work entirely within the discipline of cartooning, which is related to but quite different from illustration.

The urge to be a cartoonist is something that's clearly been burning in him because he was already quite prolific even before her arrived at CCS. Let's take a look at his comics. There are a few one-pagers, like The Great Sex Talk Of 1973. Right away, Wilson establishes his visual style: slightly distorted and grotesque figures with rosy cheeks and a restrained but prominent use of color. He's also quite funny, as this story follows seven-year-old Emil having read a book about sex and asking his mother about it. When he asks about the possibility of him impregnating her, her chain-smoking disaffectedness swats his inquiries down until Emil brings up Jesus as the reason he couldn't do it. How To Pronounce My Name is another funny one, as a barista mistook his name for "Anal" and even wrote it on his cup. This one's all in gray-scale shading with a bit of a Ben Katchor rattiness to his line. Once again, his instincts as a humorist are sharp. All About Me! The Body Edition is a single page illustration of his body, relative to various things that happened to it at various ages. Again, Wilson knows how to work a meaningful anecdote, including bits related to his husband and a lot of positive self-esteem.

Telling People is a clever mini where Wilson details the various conversations he had with people when he told them he was going to art school. The first strip outlines every second thought he had about it, from feeling isolated and out of place with younger cartoonists, to being separated from his husband, to worrying about encountering death due to Vermont's icy weather. His friend only reacted when Wilson pointed out that there were no Starbucks there. Again, Wilson has great comic timing, and visually, the page serves as a text-delivery mechanism, as he doesn't want to detract from the gag. The rest of the strips are variations on a theme, with the one where he's talking to his deluded mother being the best.

Killing Simon is a mini, I think, that may well portend Wilson's future. It's about a man who accidentally kills a family's cat right in front of them at a yard sale. He feels horrible about it, but his attempts at making amends only lead him into weirder and more awkward situations. It's an extremely uncomfortable comic that gets cringe-worthy in all the right ways. However, here we also see Wilson's limitations as a cartoonist. His figures are stiff at various points, and he doesn't have a sense of how to draw figures interacting in space. His use of gesture also needs some refinement.

Silent Witnesses was Wilson's try-out comic for CCS, and it immediately showcases two things: he's a funny writer and a distinctive stylist. However, this isn't really a comic in any traditional sense. This is illustrated text. The Turtle And The Bunny, Wilson's take on the CCS Aesop assignment, is another viscerally droll comic. Here, the layout is somewhere between illustrated text and an open-page comics layout, as a jealous pet bunny's own paranoia eventually does him in. The juxtaposition between the ornate lettering and cute use of color with the eventual grisly violence is a striking one, and the page of morals is grimly hilarious. The Princess And The Turnip is another whimsical and absurd fairy tale about a woman who falls in love with various inanimate objects, until she finally finds love with an umbrella. Once again, there's a nice contrast between the scratchy line and the elaborate lettering and lush use of color. The Taking Tree is a parody of Shel Silverstein's classic The Giving Tree, only the boy, in this case, is Donald Trump. As a parody, it's amusing; as political satire, it's a bit of a blunt force object.

Eight Nates is a funny kids' comic about a lonely kid who manages to conjure up seven copies of himself as playmates, to disastrous effect. This had an odd mix of black & white and color; I couldn't quite tell if this was deliberate. Introducing Erin Williams is a true story about a woman who stutters, and it's told as a kind of interview comic. Stuttering is an executive functioning neurological issue that is poorly understood by the lay public. This is a sharp, colorful comic that makes great use of naturalism and body language. We Will Never Be Happy Again is, as was stated in the mini itself, an illustrated poem. It's more of Wilson's grim sense of humor on display. Finally, The Pillow Of Your Dreams is a funny, well-designed "User's Manual" for a pillow that creates vivid dreams for its users. Wilson's obvious facility with this kind of drawing is what made the humor in this comic all the more effective.

I can't quite yet tell what kind of cartoonist Wilson is going to be. He's extremely skilled in some areas, but certain habits of illustration have to be un-learned before one becomes a good cartoonist and visual storyteller. Wilson is very funny, especially with regard to cringe humor, and I could see him going in that direction. The stuff he wrote about his family and friends is also funny, in an often bleak manner. CCS is a perfect place for him, because cartooning and storytelling are the bedrocks of their curriculum.

The urge to be a cartoonist is something that's clearly been burning in him because he was already quite prolific even before her arrived at CCS. Let's take a look at his comics. There are a few one-pagers, like The Great Sex Talk Of 1973. Right away, Wilson establishes his visual style: slightly distorted and grotesque figures with rosy cheeks and a restrained but prominent use of color. He's also quite funny, as this story follows seven-year-old Emil having read a book about sex and asking his mother about it. When he asks about the possibility of him impregnating her, her chain-smoking disaffectedness swats his inquiries down until Emil brings up Jesus as the reason he couldn't do it. How To Pronounce My Name is another funny one, as a barista mistook his name for "Anal" and even wrote it on his cup. This one's all in gray-scale shading with a bit of a Ben Katchor rattiness to his line. Once again, his instincts as a humorist are sharp. All About Me! The Body Edition is a single page illustration of his body, relative to various things that happened to it at various ages. Again, Wilson knows how to work a meaningful anecdote, including bits related to his husband and a lot of positive self-esteem.

Telling People is a clever mini where Wilson details the various conversations he had with people when he told them he was going to art school. The first strip outlines every second thought he had about it, from feeling isolated and out of place with younger cartoonists, to being separated from his husband, to worrying about encountering death due to Vermont's icy weather. His friend only reacted when Wilson pointed out that there were no Starbucks there. Again, Wilson has great comic timing, and visually, the page serves as a text-delivery mechanism, as he doesn't want to detract from the gag. The rest of the strips are variations on a theme, with the one where he's talking to his deluded mother being the best.

Killing Simon is a mini, I think, that may well portend Wilson's future. It's about a man who accidentally kills a family's cat right in front of them at a yard sale. He feels horrible about it, but his attempts at making amends only lead him into weirder and more awkward situations. It's an extremely uncomfortable comic that gets cringe-worthy in all the right ways. However, here we also see Wilson's limitations as a cartoonist. His figures are stiff at various points, and he doesn't have a sense of how to draw figures interacting in space. His use of gesture also needs some refinement.

Silent Witnesses was Wilson's try-out comic for CCS, and it immediately showcases two things: he's a funny writer and a distinctive stylist. However, this isn't really a comic in any traditional sense. This is illustrated text. The Turtle And The Bunny, Wilson's take on the CCS Aesop assignment, is another viscerally droll comic. Here, the layout is somewhere between illustrated text and an open-page comics layout, as a jealous pet bunny's own paranoia eventually does him in. The juxtaposition between the ornate lettering and cute use of color with the eventual grisly violence is a striking one, and the page of morals is grimly hilarious. The Princess And The Turnip is another whimsical and absurd fairy tale about a woman who falls in love with various inanimate objects, until she finally finds love with an umbrella. Once again, there's a nice contrast between the scratchy line and the elaborate lettering and lush use of color. The Taking Tree is a parody of Shel Silverstein's classic The Giving Tree, only the boy, in this case, is Donald Trump. As a parody, it's amusing; as political satire, it's a bit of a blunt force object.

Eight Nates is a funny kids' comic about a lonely kid who manages to conjure up seven copies of himself as playmates, to disastrous effect. This had an odd mix of black & white and color; I couldn't quite tell if this was deliberate. Introducing Erin Williams is a true story about a woman who stutters, and it's told as a kind of interview comic. Stuttering is an executive functioning neurological issue that is poorly understood by the lay public. This is a sharp, colorful comic that makes great use of naturalism and body language. We Will Never Be Happy Again is, as was stated in the mini itself, an illustrated poem. It's more of Wilson's grim sense of humor on display. Finally, The Pillow Of Your Dreams is a funny, well-designed "User's Manual" for a pillow that creates vivid dreams for its users. Wilson's obvious facility with this kind of drawing is what made the humor in this comic all the more effective.

I can't quite yet tell what kind of cartoonist Wilson is going to be. He's extremely skilled in some areas, but certain habits of illustration have to be un-learned before one becomes a good cartoonist and visual storyteller. Wilson is very funny, especially with regard to cringe humor, and I could see him going in that direction. The stuff he wrote about his family and friends is also funny, in an often bleak manner. CCS is a perfect place for him, because cartooning and storytelling are the bedrocks of their curriculum.

Thursday, December 26, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #26: Aaron Cockle

Aaron Cockle continues his series about a video game called Andalusian Dog with the fifth and sixth issues. Like much of his work, this is an oblique, culture-jamming satire of capitalism, technology, and utopianism. The title refers to a video game, which may or may not be responsible for global catastrophes. After a lot of activity and commands in the first four issues, this issue takes a step back to observe and talk about observing. Indeed, the theme of the issue is phenomenology, that tool of philosophy used to observe and describe. In this case, what is sought to be described is the relationship between insight and understanding. "Understanding of insight is insight of understanding," summed up this description, and this began a series of circular arguments that ended in a Sculpture Garden with no sculptures and which wasn't a garden.

Insight is often considered to be intuitive and immediate, whereas understanding is the endpoint of a process. Cockle gets at the argument that underpins existentialism here. Language is the tool of understanding, but language is inherently corrupt because it fails to address the idea of being. Insight goes beyond language; it can be described by language but it isn't the same thing as the experience. By using paradox to link them, he negates them both, creating that state he describes at the end: the sculpture garden with no sculptures that isn't a garden. It both is and isn't, just as in the last panel he describes the game-makers' place: "Our place being this place, this place being a place, a place being no place." In other words, it begins with a solid description of something we can perceive, then reduces it to its linguistic underpinnings, then takes those away because language is corrupt. It's a lot of conceptual rug-pulling.

The sixth issue is a juxtaposition of a phenomenological description of the game with raw images and neon-bright Risographed colors. Phenomenology asks that we put aside our everyday understanding of an object and its use-value before describing it. Hence, the description here is of shapes, figures, and maps. It's also a massive change from the previous issue, which used phenomenology on a conceptual level instead of a material level. I'm still not quite sure where Cockle is going to end up with all of this, but he always provides surprises in even the most conceptual of his comics.

Insight is often considered to be intuitive and immediate, whereas understanding is the endpoint of a process. Cockle gets at the argument that underpins existentialism here. Language is the tool of understanding, but language is inherently corrupt because it fails to address the idea of being. Insight goes beyond language; it can be described by language but it isn't the same thing as the experience. By using paradox to link them, he negates them both, creating that state he describes at the end: the sculpture garden with no sculptures that isn't a garden. It both is and isn't, just as in the last panel he describes the game-makers' place: "Our place being this place, this place being a place, a place being no place." In other words, it begins with a solid description of something we can perceive, then reduces it to its linguistic underpinnings, then takes those away because language is corrupt. It's a lot of conceptual rug-pulling.

The sixth issue is a juxtaposition of a phenomenological description of the game with raw images and neon-bright Risographed colors. Phenomenology asks that we put aside our everyday understanding of an object and its use-value before describing it. Hence, the description here is of shapes, figures, and maps. It's also a massive change from the previous issue, which used phenomenology on a conceptual level instead of a material level. I'm still not quite sure where Cockle is going to end up with all of this, but he always provides surprises in even the most conceptual of his comics.

Wednesday, December 25, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #25: Sandy Steen Bartholomew

Sandy Steen Bartholomew is an example of a talented, established illustrator who decides to attend CCS a little later in life. She also attended SVA and RISD, but CCS is a place you go to learn how to become a storyteller. Much of her work at CCS, including her thesis, was autobiographical. Her mix of having a sunny disposition while dealing with a complicated life and depression make for some interesting comics, as does her formal approach.

We Will Never Leave You!! is a great example of how Bartholomew works cute no matter what. This is a mini that starts with her opening up her head and letting her various, cutely-drawn demons out, as she deals with them, one-by-one. After talking to OCD (who was labeling everyone and everything), she turned to Anxiety, who melted into a puddle. Creativity and Imagination came out to play, but Divorce nearly suffocated her. There's an interesting note about her young daughter running to find Hope, Heart, and Happiness. There's a lot of tonal dissonance in Bartholomew's work, as she's willing to spill some ink and get raw & personal, but there's a surface smoothness to her line that keeps things a bit restrained.

Bartholomew is an illustrator and specializes in kids' books. Ready, Set Gorilla!, written by Melissa Stoller, plays to her strengths with regard to character design and color. Her use of colored pencils, in particular, not only adds levels of detail to the characters, but it also adds depth and weight to the pages. Negative space is used with greater intentionality as a result of color being there to soak up eyeball space on the wide-open pages. The Fright Before Christmas demonstrated her pure skill as an illustrator, with her cross-hatching, in particular, providing a dense atmosphere in this story that mixes Christmas and Halloween imagery. It's cuter than laugh-out-loud funny, which describes much of her work.

Bartholomew's most ambitious work is the expanded version of her thesis, Quo Vadis: Where Are You Going? That title is a clever play on words, as Bartholomew used an academic planner to do her daily diary strips. That meant most strips for most days were a panel or two at most, so there was some vagueness with some of her bad days. For this updated version, she added "intermissions" which spelled out some of the more emotionally tumultuous incidents in her life. That added a lot of depth and intimate detail to her day-to-day feelings. The other title for her thesis was Begin Again, and that's reflected in this being very much a post-divorce journal, even if it had ended several years prior. Bartholomew offers few details as to why her marriage ended, but her ex's role in her life, especially with a young kid, is clearly a thorny point of contention. There's a lot of unprocessed grief evident here.

Like all good diary comics, Bartholomew throws the reader into her narrative in media res. This approach was doubly chaotic for the reader because of the unsettled and chaotic nature of her own life. She was splitting time between her house in New Hampshire and her apartment in White River Junction. She had a shop that she had closed and was trying to figure out what to do with. She was beginning her final year at CCS. She was doing graphic medicine freelance work. On top of all that, she had a tempestuous relationship with a guy she called "the Fireman." She had to figure out ways to make money, take care of her elderly mother, and maintain a relationship with her college-age son.

It was disappointing that I didn't get more of a sense of what being a student at CCS was like, although to be fair the second year is thesis time, where more of the work that's being done is independent. That said, hardly any of her fellow students made much more than a cameo, which I thought was an odd choice. It may well speak to her actual interaction, as an older and more established person with a family who spent a lot of time out of town. I also didn't get a sense of what the student-mentor relationship was like either, and that is a key piece of the senior experience.

On the other hand, Bartholomew's one or two-panel approach was perfect for cute bon mots, funny drawings, and the rollercoaster of emotions she felt with her boyfriend. In the end, that's what the journal's rawest, most authentic moments of vulnerability detailed the best. There were a lot of highs that were given a lot of exposure as well as a lot of lows where one got the sense that the relationship was always going to be on borrowed time. Bartholomew only hints and tiptoes at a lot of the dysfunction, preferring to dwell on the positive most of the time. However, when the bottom fell out, it really fell out, and those days feel like scorched earth. Her pleasant, cartoony character design still worked for this kind of story, as on good days, the Fireman had flames emanating from his head and on chilly days his head would be encased in ice. I don't think Bartholomew deliberately holds back as much as that her point of view is naturally upbeat and sunny, even on hard days. The result is a consistently entertaining if not always revelatory account of the life of an artist, single mother, and hustling businesswoman.

We Will Never Leave You!! is a great example of how Bartholomew works cute no matter what. This is a mini that starts with her opening up her head and letting her various, cutely-drawn demons out, as she deals with them, one-by-one. After talking to OCD (who was labeling everyone and everything), she turned to Anxiety, who melted into a puddle. Creativity and Imagination came out to play, but Divorce nearly suffocated her. There's an interesting note about her young daughter running to find Hope, Heart, and Happiness. There's a lot of tonal dissonance in Bartholomew's work, as she's willing to spill some ink and get raw & personal, but there's a surface smoothness to her line that keeps things a bit restrained.

Bartholomew is an illustrator and specializes in kids' books. Ready, Set Gorilla!, written by Melissa Stoller, plays to her strengths with regard to character design and color. Her use of colored pencils, in particular, not only adds levels of detail to the characters, but it also adds depth and weight to the pages. Negative space is used with greater intentionality as a result of color being there to soak up eyeball space on the wide-open pages. The Fright Before Christmas demonstrated her pure skill as an illustrator, with her cross-hatching, in particular, providing a dense atmosphere in this story that mixes Christmas and Halloween imagery. It's cuter than laugh-out-loud funny, which describes much of her work.

Bartholomew's most ambitious work is the expanded version of her thesis, Quo Vadis: Where Are You Going? That title is a clever play on words, as Bartholomew used an academic planner to do her daily diary strips. That meant most strips for most days were a panel or two at most, so there was some vagueness with some of her bad days. For this updated version, she added "intermissions" which spelled out some of the more emotionally tumultuous incidents in her life. That added a lot of depth and intimate detail to her day-to-day feelings. The other title for her thesis was Begin Again, and that's reflected in this being very much a post-divorce journal, even if it had ended several years prior. Bartholomew offers few details as to why her marriage ended, but her ex's role in her life, especially with a young kid, is clearly a thorny point of contention. There's a lot of unprocessed grief evident here.

Like all good diary comics, Bartholomew throws the reader into her narrative in media res. This approach was doubly chaotic for the reader because of the unsettled and chaotic nature of her own life. She was splitting time between her house in New Hampshire and her apartment in White River Junction. She had a shop that she had closed and was trying to figure out what to do with. She was beginning her final year at CCS. She was doing graphic medicine freelance work. On top of all that, she had a tempestuous relationship with a guy she called "the Fireman." She had to figure out ways to make money, take care of her elderly mother, and maintain a relationship with her college-age son.

It was disappointing that I didn't get more of a sense of what being a student at CCS was like, although to be fair the second year is thesis time, where more of the work that's being done is independent. That said, hardly any of her fellow students made much more than a cameo, which I thought was an odd choice. It may well speak to her actual interaction, as an older and more established person with a family who spent a lot of time out of town. I also didn't get a sense of what the student-mentor relationship was like either, and that is a key piece of the senior experience.

On the other hand, Bartholomew's one or two-panel approach was perfect for cute bon mots, funny drawings, and the rollercoaster of emotions she felt with her boyfriend. In the end, that's what the journal's rawest, most authentic moments of vulnerability detailed the best. There were a lot of highs that were given a lot of exposure as well as a lot of lows where one got the sense that the relationship was always going to be on borrowed time. Bartholomew only hints and tiptoes at a lot of the dysfunction, preferring to dwell on the positive most of the time. However, when the bottom fell out, it really fell out, and those days feel like scorched earth. Her pleasant, cartoony character design still worked for this kind of story, as on good days, the Fireman had flames emanating from his head and on chilly days his head would be encased in ice. I don't think Bartholomew deliberately holds back as much as that her point of view is naturally upbeat and sunny, even on hard days. The result is a consistently entertaining if not always revelatory account of the life of an artist, single mother, and hustling businesswoman.

Tuesday, December 24, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #24: Charles Forsman

A lot of Chuck Forsman's early work dealt with uncomfortable family dynamics. Later, he added supernatural elements to these sorts of concerns in his old Snake Oil series, but he's often written about families that had holes in them. Missing parents, toxic parents and other disruptions to a normal life were familiar elements. When he was at CCS, he met fellow Max de Radigues, a Belgian cartoonist who was especially proficient in comics about teens. It was de Radigues' micro-miniseries Rough Age and later Moose that inspired Forsman to create The End Of The Fucking World and Oily Comics, which were obviously two of the most important events of Forsman's career. (Season Two of TEOTFW debuts soon on Netflix!). The two collaborated on an excellent broadsheet anthology called Caboose, but their first real collaboration is a graphic novella called Hobo Mom.

Originally published in Italy and then in France, Fantagraphics released an English translation in 2019. Overall, it's more of an interesting curiosity than a major work for either artist, partly because of its short length and the novelty of its construction. This is a true collaboration, as both artists wrote and drew it remotely. Despite that distance, it feels both like a smooth final product as well as a merger of tone with regard to their storytelling interests. The story follows a single father and his tween daughter as their lives are disrupted by the sudden appearance of his ex-wife. It's a story about how the same situation can feel completely different to different people. For Tom and his daughter Sissy, their home represents safety, security, and love. For Tasha, it represents imprisonment. Forsman and De Radigues don't go into detail as to why she feels the need to constantly stay on the move, and it's not essential. Suffice it to say that the book is about her feeling constantly torn.

The overall tone of the story is more like De Radigues' work than Forsman's. There are more quiet panels, long and lingering shots of characters in an emotional state, and in general, the tone is less anxious than a Forsman comic. The tone of the comic is harsh and visceral at times, like when Tasha is riding the rails and a guy tries to sexually assault her. When Tom and Tasha have sex, there's a tenderness to it, but it's also raw and intense. Sissy catches her mom dressing and it's clear that it's not only the first time that she's seen a naked woman, she also has an understanding that this is what she will look like in the future. Though Sissy was never directly told that Tasha was her mom, it was obvious to her.

For a moment, there's a whiff of a happy ending. Tasha missed her family and spent a few idyllic days with them. When Tom asked her to stay, she imagined what that life would be like. There was a page with a 12-panel grid containing seemingly pleasant images of what daily life would be like: the rooms she'd be in, the edge of the property, doing laundry, etc. Taken as a whole, it resembles a cage or a prison door. Even trying to imagine picnics in wide-open spaces with her kid didn't diminish that sense of anxiety. Her aversion to routine is so intense that she had to leave for her sake and the sake of everyone else. The love of her daughter required something of her that she couldn't give. So many of the visuals in the book are either about wide-open spaces and freedom or restrictive spaces, like a bunny cage. Tom is a locksmith who could force or finesse his way through any barrier except his wife's heart. Though the story is a spare one, both cartoonists put a lot of thought into its emotional narrative, and the result is surprisingly resonant.

Originally published in Italy and then in France, Fantagraphics released an English translation in 2019. Overall, it's more of an interesting curiosity than a major work for either artist, partly because of its short length and the novelty of its construction. This is a true collaboration, as both artists wrote and drew it remotely. Despite that distance, it feels both like a smooth final product as well as a merger of tone with regard to their storytelling interests. The story follows a single father and his tween daughter as their lives are disrupted by the sudden appearance of his ex-wife. It's a story about how the same situation can feel completely different to different people. For Tom and his daughter Sissy, their home represents safety, security, and love. For Tasha, it represents imprisonment. Forsman and De Radigues don't go into detail as to why she feels the need to constantly stay on the move, and it's not essential. Suffice it to say that the book is about her feeling constantly torn.

The overall tone of the story is more like De Radigues' work than Forsman's. There are more quiet panels, long and lingering shots of characters in an emotional state, and in general, the tone is less anxious than a Forsman comic. The tone of the comic is harsh and visceral at times, like when Tasha is riding the rails and a guy tries to sexually assault her. When Tom and Tasha have sex, there's a tenderness to it, but it's also raw and intense. Sissy catches her mom dressing and it's clear that it's not only the first time that she's seen a naked woman, she also has an understanding that this is what she will look like in the future. Though Sissy was never directly told that Tasha was her mom, it was obvious to her.

For a moment, there's a whiff of a happy ending. Tasha missed her family and spent a few idyllic days with them. When Tom asked her to stay, she imagined what that life would be like. There was a page with a 12-panel grid containing seemingly pleasant images of what daily life would be like: the rooms she'd be in, the edge of the property, doing laundry, etc. Taken as a whole, it resembles a cage or a prison door. Even trying to imagine picnics in wide-open spaces with her kid didn't diminish that sense of anxiety. Her aversion to routine is so intense that she had to leave for her sake and the sake of everyone else. The love of her daughter required something of her that she couldn't give. So many of the visuals in the book are either about wide-open spaces and freedom or restrictive spaces, like a bunny cage. Tom is a locksmith who could force or finesse his way through any barrier except his wife's heart. Though the story is a spare one, both cartoonists put a lot of thought into its emotional narrative, and the result is surprisingly resonant.

Monday, December 23, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #23: Kristen Shull

Kristen Shull, a second-year student at CCS, is a classic example of a young cartoonist getting better in public. By doing a daily four-panel diary comic, she cranked out a year's worth of pages. Lynda Barry once recommended that every young cartoonist should do a diary for a period of time, be it a month or three months or a year. It keeps your pen going no matter what, forces you to condense events into tight stories, and challenges you to come up with storytelling solutions as a draftsman. Shull's diary strips, collectively titled Ego Gala, were engaging from the very beginning, but it was clear that by June, she had begun to really settle into a more fully realized style. In many respects, Shull's comics are a model for cartoonists considering this endeavor. Let's go down the list of what she did right:

1. Start off in media res. Shull's first strip was about having a hangover, a shitty day at work, and watching TV with a housemate. Diary strips aren't about context; they're about life lived at a moment in time. It forces the cartoonist to make their life coherent to outsiders in just four panels, every day, filling in backstory only when it makes sense to do so.

2. Funny rhythms. Diary strips work best for cartoonists who are funny, and that's certainly true of Shull. Even if there's not a traditional gag in the final panel, that final panel beat completes a thought. In general, however, Shull's enthusiasm and self-deprecatory sense of humor, as well as her willingness to do outrageous and silly things, makes the reader eager to see what she might do next.

3. Spill some ink. The worst thing a memoir can do is gloss over what it truly means to be human on a daily basis in favor of narrative concerns. Shull lets it all out: she shares about being anxious, being depressed, being horny, being excited, being excited, and so forth. One gets the sense that she can't not be honest, even if she later regrets drawing scenes of herself having sex or making references to masturbating. It's all part of a life being lived, and Shull is clearly a person who seeks out experiences.

4. Have a through-line. Shull is telling the story of being a student at CCS about all else. What is that experience like, as she is a full-time student who also has to work full-time? How does she handle assignments? What's her relationship like with her fellow students? The contrast between her daily life as a barista/waitress and student and her frequent travels make each more interesting. The toil of her daily routine compared to her bacchanalian experiences at rugby trips is especially interesting, especially because she's careful to note the lingering effects of certain experiences.

5. Show your style. Once you have the rules down, then you can break them. There's a tremendous strip where she learned that one of her closest friends had committed suicide. She drew ink splattering out and seeping into every other panel before she learned this revelation, as though hearing that her friend had died affected both her past and present. She exaggerated figures and facial expressions to strong effect throughout.

6. Simplify. It's clear that Shull started off wanting to draw in a fairly naturalistic style, but the result was a lot of sloppy figures. Some of those were made worse by occasional attempts at over-rendering. Of course, as I 've often said, illustrating and cartooning are two separate but related fields. Shull doesn't have the natural chops of a top-notch illustrator, but her instincts as a cartoonist are spot on. By the time June rolled around, Shull started to really lean into her cartooning and find her own style. The pages are clearer and more effective. Faces are simplified but also more memorable. Basically, Shull had to figure out simple, effective ways to make her pages work if she was going to continue to do her diary comics, because it is a grind. You can only hide one's weaknesses for so long until you find a way to address them, and it's to her credit that she slowly found ways to evolve over this span of time.

Shull's non-fiction assignment, Howard Blackburn, had a great premise: the story of a man who managed to survive an icy fishing trip, at the price of losing his hands. The layout and imagery were all clever, but the actual drawing looked rushed and Shull's figures interacted awkwardly in space. Shull revealed in her diary how much trouble she had with the assignment, running out of time to do it the way she wanted.

Finally, her end-of-year assignment was a fantasy comic called Terra Viscera. One can see the lessons she learned from her diary comic at work here. While the rendering in this piece is a bit more detailed than in her other work, she kept her faces relatively simple and easy to remember. Shull would add details like scars, elongated faces, and other visual tricks to help the reader keep track of who was who. Shull then nails the complicated battle scenes, and it seems like all of the experience spent on doing nothing but drawing bodies interacting in space and body language paid off here. What was especially effective in this comic was the final-scene plot-twist that was hiding in plain sight the whole time.

1. Start off in media res. Shull's first strip was about having a hangover, a shitty day at work, and watching TV with a housemate. Diary strips aren't about context; they're about life lived at a moment in time. It forces the cartoonist to make their life coherent to outsiders in just four panels, every day, filling in backstory only when it makes sense to do so.

2. Funny rhythms. Diary strips work best for cartoonists who are funny, and that's certainly true of Shull. Even if there's not a traditional gag in the final panel, that final panel beat completes a thought. In general, however, Shull's enthusiasm and self-deprecatory sense of humor, as well as her willingness to do outrageous and silly things, makes the reader eager to see what she might do next.

3. Spill some ink. The worst thing a memoir can do is gloss over what it truly means to be human on a daily basis in favor of narrative concerns. Shull lets it all out: she shares about being anxious, being depressed, being horny, being excited, being excited, and so forth. One gets the sense that she can't not be honest, even if she later regrets drawing scenes of herself having sex or making references to masturbating. It's all part of a life being lived, and Shull is clearly a person who seeks out experiences.

4. Have a through-line. Shull is telling the story of being a student at CCS about all else. What is that experience like, as she is a full-time student who also has to work full-time? How does she handle assignments? What's her relationship like with her fellow students? The contrast between her daily life as a barista/waitress and student and her frequent travels make each more interesting. The toil of her daily routine compared to her bacchanalian experiences at rugby trips is especially interesting, especially because she's careful to note the lingering effects of certain experiences.

5. Show your style. Once you have the rules down, then you can break them. There's a tremendous strip where she learned that one of her closest friends had committed suicide. She drew ink splattering out and seeping into every other panel before she learned this revelation, as though hearing that her friend had died affected both her past and present. She exaggerated figures and facial expressions to strong effect throughout.

6. Simplify. It's clear that Shull started off wanting to draw in a fairly naturalistic style, but the result was a lot of sloppy figures. Some of those were made worse by occasional attempts at over-rendering. Of course, as I 've often said, illustrating and cartooning are two separate but related fields. Shull doesn't have the natural chops of a top-notch illustrator, but her instincts as a cartoonist are spot on. By the time June rolled around, Shull started to really lean into her cartooning and find her own style. The pages are clearer and more effective. Faces are simplified but also more memorable. Basically, Shull had to figure out simple, effective ways to make her pages work if she was going to continue to do her diary comics, because it is a grind. You can only hide one's weaknesses for so long until you find a way to address them, and it's to her credit that she slowly found ways to evolve over this span of time.

Shull's non-fiction assignment, Howard Blackburn, had a great premise: the story of a man who managed to survive an icy fishing trip, at the price of losing his hands. The layout and imagery were all clever, but the actual drawing looked rushed and Shull's figures interacted awkwardly in space. Shull revealed in her diary how much trouble she had with the assignment, running out of time to do it the way she wanted.

Finally, her end-of-year assignment was a fantasy comic called Terra Viscera. One can see the lessons she learned from her diary comic at work here. While the rendering in this piece is a bit more detailed than in her other work, she kept her faces relatively simple and easy to remember. Shull would add details like scars, elongated faces, and other visual tricks to help the reader keep track of who was who. Shull then nails the complicated battle scenes, and it seems like all of the experience spent on doing nothing but drawing bodies interacting in space and body language paid off here. What was especially effective in this comic was the final-scene plot-twist that was hiding in plain sight the whole time.

Sunday, December 22, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #22: Jai Granofsky, DW

It's funny; whether or not DW sends me something directly for review, he always winds up in my yearly CCS round-up anyway. That's because he loves collaborating with other CCS folks. This year, it's a comic's worth of collaborations with Jai Granofsky. The sole thing I had reviewed from him was Waiting For Baby, a bracing and frequently grim bit of memoir. It's clear that his real forte' is absurd, weird, and sometimes transgressive vignettes. In Taglianuccis, he and DW switch off on creative duties. "Cerrito" is a surreal account of a film director's life as told by a woman who knew him slightly. DW wrote this and Granofsky drew it, and it's interesting to see how Granofsky drew a lot of extra detail in order to give the reader something to look at. The story itself seems to be about familiar creators until DW threw in weird details about magical beasts. "Home Away" was written by Granofsky and drawn by DW in his stripped-down style that resembles an Ed Emberley drawing. It's every bit as weird as the other comics, as two creatures first discuss scatological functions in a refined manner and then talk about an assassination assigned to them. The rhythm of the whole thing reminded me of a Gerald Jablonski comic.

The humor ranges from absurd to upsetting to things based on misunderstandings, like a DW-written strip about a man who misidentifies the actor Garret Dillahunt as Garrison Keillor in a bar. There's a weird flatness to the work that looks partly deliberately banal and partly sinister. That's true of so much of this comic and Granofsky's work in general. It's mostly naturalistic, so the weird flourishes or monstrous figures are especially disturbing and unexpected. Granofsky's own comic, What The Actual, is every bit as odd as his collaborations with DW. There's a vibe that's sort of a cross between Eric Haven's embrace of mainstream tropes and Paul Hornschemeier's skill in cartooning and rendering in a style the blends naturalism with certain cartoony flourishes.

In "Old Friends," for example, a guy who looks like a drawing out of a Billy DeBeck comic strip meets up with a guy who could be in a Harvey Pekar story. The result of their meeting is a violent fight, a car crash, a decapitation, and a juvenile meta-joke. There's a story about a "party donkey" and the world's most violent game of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey as two kids try to one-up each other. There's a story about a kid who gets a guy to come over to play a video game with him as the world is about to end and fried chicken is delivered by helicopter. An astoundingly vicious masked superhero delivers "justice" that's ridiculously disproportionate to the original infraction. Granofsky is deliberately messing with genre tropes here, either by exploding them or taking them to extremes.

In the second issue of What The Actual, Granofsky runs a bunch of different narratives together. It starts with "Midnight Motor Mike," a stunt cyclist who deals with a heckler by pulling him out of the audience and threatening to shit down his throat. There's a funny flatness of affect in the dialogue, as though Granofsky was piecing together terrible grindhouse movies together. Another story features an anthropomorphic duck who loves to text. The next features two women who are running from some kind of invincible zombie creature, ala a standard horror film. All of these storylines then mash together, as the women stumble on Midnight Motor Mike. Several eviscerations later, the original heckler of the cyclist seems like he's about to get his revenge before the masked hero from the first issue shows up out of nowhere. The texting duck is even connected to everyone, as the unseen victims of the zombie are his friends as well. The whole package is just...odd. There's a feeling of stream-of-consciousness at work, but also a creative process akin to long-form improv. There's nothing quite like it in comics at the moment, where Granofsky just goes straight to his id for inspiration and finds it mediated by a variety of pop culture influences.

The humor ranges from absurd to upsetting to things based on misunderstandings, like a DW-written strip about a man who misidentifies the actor Garret Dillahunt as Garrison Keillor in a bar. There's a weird flatness to the work that looks partly deliberately banal and partly sinister. That's true of so much of this comic and Granofsky's work in general. It's mostly naturalistic, so the weird flourishes or monstrous figures are especially disturbing and unexpected. Granofsky's own comic, What The Actual, is every bit as odd as his collaborations with DW. There's a vibe that's sort of a cross between Eric Haven's embrace of mainstream tropes and Paul Hornschemeier's skill in cartooning and rendering in a style the blends naturalism with certain cartoony flourishes.

In "Old Friends," for example, a guy who looks like a drawing out of a Billy DeBeck comic strip meets up with a guy who could be in a Harvey Pekar story. The result of their meeting is a violent fight, a car crash, a decapitation, and a juvenile meta-joke. There's a story about a "party donkey" and the world's most violent game of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey as two kids try to one-up each other. There's a story about a kid who gets a guy to come over to play a video game with him as the world is about to end and fried chicken is delivered by helicopter. An astoundingly vicious masked superhero delivers "justice" that's ridiculously disproportionate to the original infraction. Granofsky is deliberately messing with genre tropes here, either by exploding them or taking them to extremes.

In the second issue of What The Actual, Granofsky runs a bunch of different narratives together. It starts with "Midnight Motor Mike," a stunt cyclist who deals with a heckler by pulling him out of the audience and threatening to shit down his throat. There's a funny flatness of affect in the dialogue, as though Granofsky was piecing together terrible grindhouse movies together. Another story features an anthropomorphic duck who loves to text. The next features two women who are running from some kind of invincible zombie creature, ala a standard horror film. All of these storylines then mash together, as the women stumble on Midnight Motor Mike. Several eviscerations later, the original heckler of the cyclist seems like he's about to get his revenge before the masked hero from the first issue shows up out of nowhere. The texting duck is even connected to everyone, as the unseen victims of the zombie are his friends as well. The whole package is just...odd. There's a feeling of stream-of-consciousness at work, but also a creative process akin to long-form improv. There's nothing quite like it in comics at the moment, where Granofsky just goes straight to his id for inspiration and finds it mediated by a variety of pop culture influences.

Saturday, December 21, 2019

31 Days Of CCS #21: Filipa Estrela