Andy Warner, along with Josh Kramer, Eleri Mai Harris, Dan Nott, Dan Archer, and a few others, make up a group of CCS grads whose primary interest is in comics journalism. Unsurprisingly, Warner has been a longtime mainstay of The Nib, and he's one of their best contributors. His minicomic, Eruption, is a good example of his Nib work. It's meticulously-researched, thought-provoking, and provides a human angle on everything. This is about the eruption of Mt. Kilauea in Hawai'i a few years back. In his clear, rich detailed drawing style, he gives the reader a sense of what it was like when the volcano erupted, but he also provides information as to the implications and repercussions of the event, both geologically and economically.

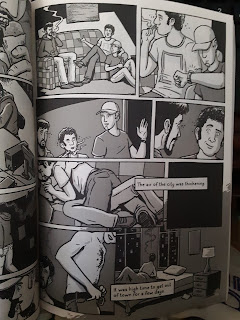

On the other hand, Spring Rain, his memoir of being in Beirut in 2005 when a revolution was breaking out, is sprawling, self-indulgent, messy, and raw. As he discusses in the book, he's told a lot of stories about Beirut in the course of his comics career, but he always left out all of the significant personal details. This book integrates a significant mental breakdown he experienced, the fraught relationships he was dealing with, and the extremely tenuous political situation that exploded around him. All at the age of 21.

Writing this kind of book was an all or nothing proposition. After years of holding back, Warner had to discuss everything, no matter how embarrassing or painful it was. It's clear that he was as honest as he possibly could be in telling this story, because he does not make himself a sympathetic character. Indeed, his time in Beirut could be described as a continuous series of bad decisions, starting with breaking up with his girlfriend in America prior to the trip, for no reason other than being apart. He regretted it immediately and talked to her via email when he could, but it was obvious that he had unfinished business there and it gave him a baseline level of misery.

That was balanced against Warner making a number of remarkable friends. Some were natives of Lebanon, while others were from the US like he was. Living abroad, it wasn't surprising that the isolation of this experience would lead to him making such fast friends, and it was clear that they knew that he needed them. They encouraged him to go out instead of stewing alone in his depression. A major subplot of his story was that many of these friends were gay men, which puzzled a few since Warner was ostensibly straight.

That in itself was a key element of the book: Warner coming to terms with his own sexuality and how that related to trauma. An incident from high school where a guy he wanted to be friends with grabbed Warner's crotch against his will confused and traumatized him. That led him to stop trying in a class, and one day the teacher punished him by laying him down on the floor and telling him to hump it. Shame, rage, humiliation--all bottled up. On top of all that, Warner's family had a history of mental illness. All of that subsumed trauma combined with genetic tendencies made Warner a ticking time bomb.

Throw all of that on top of a genuine political uprising that alternated moments of hope and solidarity for the Lebanese with cynical machinations by Syria, the PLO, and America, and you had an almost absurd outward manifestation of the roiling paranoia and despair that Warner felt. Indeed, almost every one of his friends had their own inner struggles. One gay friend took a bunch of pills to kill himself because he knew his parents would never approve of him. As the world became more uncertain, Warner's relationships with his friends grew closer but also more unstable. His next-door neighbor and close friend came on to him despite him having a boyfriend, but Warner agreed to hook up with him several times. He had sex a few times with one of his female friends and both tried to pretend it didn't mean anything until it did. When he tried to get her to hook up with someone else at a party, it was an act that demeaned and hurt her. Of course, the group throwing drugs into the equation did little to calm things down. All that did was accelerate the madness, matching the madness around them.

Warner's own depiction of his breakdown and near-suicide attempt is harrowing. It was unsparing and used the full range of his considerable skill as a draftsman. For weeks, he had heard voices. He had seen threatening faces. The whispers grew louder on that night, and then eventually they passed. It is no coincidence that he had decided to do a story about his high school experience, releasing that trauma a little. The importance of art in Warner's life is one of the big emphases in this book; he never comes out and says it, but it's obvious that art saved his life. It's also clear that writing this book is something he had to do. Everything that happened was too big to wrap his mind around, but he couldn't help but try to do it anyway. Warner tries to give the reader a sense of Beirut and its history, what its people are like, and what it's like to be a student abroad. Then he tries to do this as a completely unreliable narrator in a volatile political situation while on drugs. It never quite coheres, but neither did his experiences. A bunch of horrible and beautiful stuff happened to Warner. He made a number of bad decisions and hurt some people's feelings as a result. He made it through as best as he could, and came clean with regard to trauma and mental illness through his art. If nothing else, he paid a debt to himself and others by being open about what happened to him in Beirut, bridging the gap between journalism and memoir in a graphic, compelling, and expansive manner.

No comments:

Post a Comment