For Ibrahim R. Ineke, horror is hidden and forgotten knowledge brought to light. It's poking around in the woods and seeing things not meant to be seen. It's encountering ancient beings that look like children whose presence will bring no good. It's forbidden speech being spoken aloud, forbidden rituals made part of the everyday. It's the understanding that civilization is a facade, something that will fall away in time and be overtaken by the forest and its denizens. Ineke has been working and reworking self-published adaptations of Arthur Machen's 1904 story "The White People" over the last couple of years, culminating in a hardback publication issued by Dutch publisher Sherpa in 2015.

Ineke has long used three visual techniques. First, there's his own elegant pen-and-ink line. There's a delicacy, almost a fragility to his line that nonetheless allows for a great deal of naturalistic detail. His faces are mostly naturalistic, though they do have a slightly cartoonish quality that sometimes turn into twisted, terrifying images. His second technique is an extensive use of photocopying to repeat and distort images, often using double and even triple exposure. Along with the increasingly dark images generated by photocopying, Ineke also uses a lot of thinly-applied white-out as a mark-making technique.

In The White People, that white-on-black imagery opens the book as we see a number of figures deep in the woods notable for their lack of presence. They take up white space but have no other definition. Then comes a scene that Ineke has repeated in a number of comics: two boys playing in the woods, playing at being warriors or wizards (one even invokes Lovecraft lore and Cthulhu) and one boy running a little ahead of the other. In a slow burn of one panel stacking atop the other and the images getting bigger, we see one kid sitting in a field, his head half disappeared. Ineke flips from the bright sun illuminating a field to a dark cave (jotted with dots of white-out) with waterfalls. The child is looking at another world and is forever changed. In the book, Ineke then repeats the interaction, this time in color, and then repeats it again, this time with the implication of ritualistic kidnapping. There's a chilling image of a child turning around and their face being the image of a sinister-looking house, one where it's implied all sorts of awful things take place, followed by a full-page shot of a feral child-like thing. The book ends with two detectives looking for the missing boys, with one of them oblivious to his surroundings and the other all too aware of what the woods represent, especially with regard to "the good folk" or fairies.

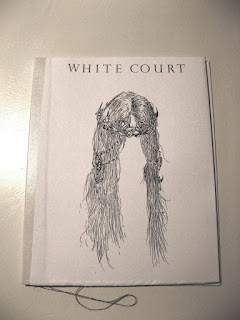

An earlier minicomics version of the story with the same title included an introduction that made this connection between the city's men of power and their occult connections that involved the ritualistic abuse of children, including a reference to a sequence of symbols that appears in the stories. While this was useful, Ineke's decision to excise that bit made sense given his emphasis on imagery and suggestion over explicit explanation. Witch Route is a short mini with some forest scenes and some key (reprinted) text about testimonials regarding children who had passed through fairy territory and came back horribly changed. Again, it's an establishing text that later became assumed and tacit. White Court is a hand-bound and assembled mini that makes the connection between kids and fairies more explicit, as it starts with a stag hunt that turns on the hunter when he is surrounded, turns to a man playing a flute being seduced by a fairy, and then segues to a different version of the two kids playing at combat with each other, this time in an abandoned building and direct intervention from fairies. There's a more structured division between chapters and additional scenes, none of which are more effective than what wound up in the book.

Also worth mentioning is No Maps, which is a collaboration with Niels Post alternating spam comments from the internet with Ineke's imagery. The images range from spare to intense to horrific to amusing. Eloise is about a missing young woman and starts with violent, ritualistic image at a punk show mashed up with imagery from Catholic ceremonies. That juxtaposition, of rebellion vs tradition, is at the heart of the comic in the way that her story is one of betrayal by those she loved most. It relates to the other comics in the way she rejects the city and what she has known before and instead embraces nature and the outdoors, ending the book climbing a mountain (and perhaps not coincidentally wearing a jacket with the named of the punk group The Damned on it). Here, it's all scribbles and texture with line instead of other effects.

Finally, there's the anthology miniseries Black Books, where every issue also feels like a lab for a larger story. Each issue begins with a reference to Saturn in an astrological sense, and each story has its own twist on horror. The first issue is yet another version of the two boys playing in the woods, this time with an explicitly vicious ending. The second issue is a darkly funny retelling of the fate of Orpheus, his severed head forever alive, meeting up with a Muse who uses his head to perform cunnilingus and then kisses him--and then tosses him away. The third issue returns to the city, where secret arrangements add a sinister quality to interactions between lovers and the custody of children shared between families. The fourth issue lifts dialogue from an earlier comic and makes it an interaction between a lord and a servant, who gives him a report in comic book form that is rejected but triggers a sort of breakdown of reality. The fifth issue is about a heist gone horribly wrong when reaching the forest and includes tales of a Robin Hood-style archer causing mayhem before the reveal of a ghastly child (an image used in The White People). Finally, the sixth issue is about a merciless, pitiless witch deftly outwitting a spiritual world full of male forces.

No comments:

Post a Comment