Vague Tales, by Eric Haven. In a lot of ways, Vague Tales, is the logical conclusion to the sort of comics Haven's been doing for a long time. The weird attachment to barbarian stories, witchcraft, monsters, superheroes and regular guys standing their living room have all formed the background of his storytelling interests for years. The level of craft he attaches to each demonstrates a familiarity and an affection for genre tropes that is undeniable, yet he comes at them in such an odd way that it's hard not to chuckle at his storytelling decisions. This is not naive storytelling that is funny in spite of what the author intends; rather, Haven's approach is clearly entirely calculated. The riffs on slice-of-life comics spinning out of control make that obvious. The reason why it works is because his use of mostly silent storytelling adds a level of dryness to the proceedings that is often lacking in overheated genre potboilers, where writers insist on purpling up the prose to within an inch of the story's life. Instead, Haven focus on what a kid would see: striking images, strung together in such a way where it's easy to understand what's happening, even if the reader has no clue as to why.

That titular vagueness helps make the stories funny. What sets apart this very slight book (just 74 pages, including the end papers) is the way Haven throws story after story at the reader and then has them bleed into each other in unexpected ways. It opens with a man standing in his living room, but the first story proper is "Psylicon", which is four pages of a crystalline man with thoughts like "ponder" and "brood" whose head explodes on the last page. It's a parody of 70s Marvel comics filled with cosmic characters who moped around the universe. "Ruin" features an emaciated ghoul of a woman (a favorite Haven trope) who flies around in a biplane, shoots down a spaceship and sucks the souls out of the pilots before they crash. "Pulsar" features a barbarian character who looks uncannily like the 1970s Captain Marvel character with his costume all but torn off, and he decapitates a monster. "Sorceress" finds the titular character going into a mountain until she encounters the head of the crystalline man.

That's the pivot point for Haven, who suddenly brings all the characters crashing together. There are fights, mysterious connections, and as is often the case in a Haven comic, the end of the world. Only it isn't--it might be just a thought in the crystal man's head, or in the imagination of the man in his living room, who is only flesh and bone, as both the cover and the last page of the story indicate. What does it mean? Well, it's vague. Every story is about pointless violence, pointless destruction and a general dealing in pointlessness. Why does anyone do anything in these stories do anything? They obviously feel compelled, which is funny considering the man in the living room seems to have no compulsions or agency of his own, other than to daydream and imagine other characters with a purpose, no matter how banal or pointlessly violent. They're vague because the limits of the man's imagination allow them no further shape. They're the images of a man-child, and it seems that Haven is satirizing that tendency toward indulging this sort of infantile fantasy as much as he is celebrating it.

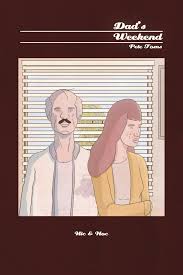

Dad's Weekend, by Pete Toms. This is a character study that is impeccably structured. It's about a conspiracy theorist and his young adult daughter, and their attempt to reconnect over a weekend. It's a funny, slow-burning, slow-building story that is also genuinely sad. The story is mostly told from the highly sardonic point of view of his daughter Whitney, and the story starts with her friends telling hilariously detached stories about their horrible futures, including one who plans to be a "failed arthouse film director", going into great detail how he will accomplish such a thing. Whitney has her own "20 year plan" of failure which is equally funny, as she and her dad exchange quips. Then the already-strange story takes a weird turn, when Manny (the dad) finds out that a friend of his is missing. This leads to a hilarious but unsettling series of events where he talks to his wife, detects something off about her and then throws a hot drink in her face.

Essentially, he was so deep in conspiracy theory decoding that he had altered his own perceptions, or rather lived in a world where what was coincidence or a trick of the ey. e became proof that his friend's wife was a lizard person. When he was found dead ("he ran himself over in a parking lot"), Manny attends the funeral and screams "This funeral is a false flag!" Eventually, he reveals the source of his paranoia: the existence of his daughter. When he saw what he perceived as the sheer terror of being alive in her eyes as an infant, it drove him from being a person who saw meaning in nothing to someone who desperately yearned to find the secret meaning of everything. It's classic conspiracy thinking, in that it's better to believe that some horrible force is in control of the world (and hence your life) than to believe that nothing and no one is control, and that everything is random and chaotic. Toms is playful at times with regard to the reality of the situation (especially in the last panel of the story), but the reality is less important than that conspiracy theorist's state of mind. The paradox is that "awareness" of the conspiracy induces a kind of debilitating madness that's exactly what They would want for you anyway. Visually, the comic has an odd flatness to it. It looks like it was drawn on a computer, and it relies on color fills quite a bit to tell the story. The strange visual tone of the comic is a perfect match for the flatness of affect of both of the main characters, who both deflect the sad reality of their situations by denying it in some way

No comments:

Post a Comment