(Yes, I know that 31 is greater than 30. I had too many artists to keep it to a mere thirty days!)

Cole Closser is an oddity in the world of alt-comics. Plenty of cartoonists have drawn inspiration from the golden age of comic strips, from R.Crumb to Chester Brown to Kim Deitch and beyond. Closser is a different case, as it's not so much that he's modeled his work after any one cartoonist in particular as he's almost become a man out of time in terms of his aesthetic, down to the most minute of details. His first book, Little Tommy Lost, was an example of Closser channelling Harold Gray by way of Milt Canniff, creating an action-adventure story featuring an orphan in a sinister orphanage. From the flat color scheme to the crude energy on every page, Closser's intent on creating a strip that would have not looked out of place on a comics page in 1930 was certainly successful. But to what end?

While I thought his first book was interesting, it felt gimmicky. On the other hand, his latest book with Koyama Press, Black Rat, sees Closser raise his game to another level. I can't even begin to suss out every influence at work here, and I'm not sure it really matters. Closser isn't interested in a spot the influence game; instead, he's crafted a truly strange, beautiful and compelling series of vignettes all centering around the titular character.

While the Black Rat sounds like it would be a monstrous or frightening character, he's actually an anthropomorphic rodent not unlike Mickey Mouse. The fluidity of the character allows him to be the star of several crude and hypnagogic action-adventure stories, a series of rhyming couplets, a text-heavy series of spiralling lines, a dreamy set of images with text, a fairy tale, and a silent horror story.

The endpapers have crude drawings that look as though they were made by Closser as a child, and there's a brief introduction where the Black Rat finds a magic object that will help him "live forever".

That's certainly true in the sense that he becomes a pervasive, omnipresent fictive force who is almost always a sidekick or something for a protagonist to react to. In the first story, a man working at a desk repeatedly uses the same magical cube the Rat finds in the introduction to unlock doorways into adventure, becoming more crudely-drawn and kinetic as a figure once he arrives in each adventure scenario. He's a forward-pushing, quipping, unstoppable force and the Black Rat is simply there to assist him and act as a sort of Greek chorus. This story shows the thin line between different levels of reality, as the hyper-real drawings between each adventure and the souvenirs the man brings back demonstrate different kinds of awareness.

"Ill Omens" features the Black Rat desperately trying to help a man calm down before forces beyond his control sense the man's fear and bring about his doom. The blotchy quality of this story gives it the feeling of being an abandoned artifact discovered and reprinted. The rich colors of "Air Ships", the cursive writing and the structure of each page evokes the wonder of a Winsor McKay or Lyonel Feininger. "Cat Teeth"'s crude line makes one feel as though one is reading a child's energetic and enigmatic story.

"Boy Blanc" and "Bow White" feel like flip sides of each other. The action and drawings in each are a bit less crude than in the first story, even as both are entirely fictive and don't have the same levels of reality-bending as the first story. In "Boy Blanc", the Black Rat is especially bright and cheerily-rendered, his strange pentagonal ears on prominent display as he and his Tough Boy Prototype partner fight off aliens with their fists and quips. "Bow White" uses lettering that's almost identical to what Edie Fake uses in his comics. The story, involving stopping earthquakes by travelling to the center of the earth, has its share of psychedelic moments and often uses language to create dissonance on the page.

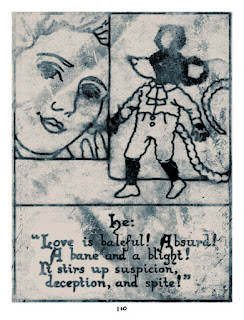

"Our Watch" and "The Chase" use the Black Rat in an entirely different manner. In the former story, the Rat is found underneath a tree by children, as a rhythm is created in how they perceive and write about this huge, mysterious figure that's come into their lives. It has all the hallmarks of originating in an obscure child's storybook. 'The Chase" is about the good old metaphor of love being both nurturing and destructive, told in rhyme and once again employing the sort of splotchy print quality that makes the reader want to connect it to something from the 1800s.

More than anything. what Closser demonstrates here (other than an astounding facility in any number of visual and printing techniques) is an ability to harness the energy of older works in a manner that rewards an attentive reader with an open mind. It recalls the wildness of early comics, when cartoonists would try anything to see if it would stick. That's part of Closser's goal here, to be sure, and it's certainly what made this so remarkably readable despite its density and variety of approaches. However, Closser is also clearly interested in the power of an iconic figure like Mickey Mouse and how the reader's instant familiarity and identification with a fairly blank slate of a character make him mutable in all sorts of interesting ways. It's as though the Floyd Gottfredson approach to Mickey (also a clear influence) here become the dominant approach in popular culture, as opposed to the sanitized, bland promotional icon that Mickey became. Closser imagines a world where Mickey was a subversive, if familiar character, one where anything could happen in the world he inhabited. Indeed, the simply invocation and appearance of the character was a harbinger of high weirdness, drama and anything else the author or reader could imagine.

No comments:

Post a Comment