Let's take a look at Mome #20 and #21. Both were decent but mostly unremarkable issues, burdened somewhat by some of the serials that bogged down the newer work. Let's go artist by artist and examine what was produced.

Dash Shaw: In #20, Shaw continued his recent attempts at adapting trashy dating TV shows like Blind Date (minus the wacky commentary and pop-ups that serve to interrupt the audience's experience of the couple on their date). Shaw's trying a lot of different things here: it's partly an experiment in having color drive the emotional narrative of a story. The subdued sea green wash here befits the low-key nature of the interaction. Shaw also omits the wacky trust-building activity central to each date in favor of simply following the couple around as they drive to their date, walk around and eat dinner. This also reflects his interest in exploring how two people interact in real life and how that translates to a page, while still retaining the staged quality of the TV show. I feel like this is all part of some larger problem-solving activity for Shaw, much like his comic about the making of Jurassic Park in #21. That documentary concerns itself with trying to create a relationship between things on a screen that don't exist (dinosaurs) and actual actors, trying to find ways to make that relationship come alive when seen in a theater. In a sense, this is what Shaw is trying to accomplish by pushing the envelope of multilayered drawings with a different color wash attached to them. He's not trying to create something real; he's trying to create something that feels real in an emotional and apprehensive sense.

Sara Edward-Corbett: In #20, her "The Bird, the Mouse and the Sausage" was one of her best pieces. Her comics have always had the preciseness of certain kinds of children's illustration, and this story is very much in the vein of a fable. Her use of negative space is exquisite, be it the bright white space in nearly every panel or the deep black of her trees, marked only be a series of thin, white vertical lines. As a result, the spot colors she uses really pop out on the page. The story is about an essentially polyamorous (but asexual) trio whose equilibrium is shattered when the bird mates with another bird. An act of jealousy winds up dooming both the mouse and the sausage, who calls into questions its very identity as an anthropomorphic being in the course of the story. Like most of her work, it's funny, sad and a little savage. In #21, "Afraid of the Dark" is a whimsical, delightfully-drawn story about an anthropomorphic desk, umbrella and box kite that leave a classroom late at night to wander the forest and cemetery. The denseness of her hatching and cross-hatching provides an interesting contrast to the benign nature of the story itself. It's a mood piece above all else, but that mood is "whimsical".

Josh Simmons and The Partridge in the Pear Tree: These two issues saw parts two and three of the truly demented serial "The White Rhinoceros". Two people (one of them apparently being 1970s Paul Lynde in full "Uncle Arthur" mode from the TV show Bewitched) find themselves in a terrifying and brightly colored forest full of what a couple of children call "racial magic". What Simmons and collaborator "Shaun Partridge" do here is transpose the most virulent of racial slurs into a fantasy world where those words have a completely different (and usually either neutral or positive) meaning. This world is quite dangerous for the newcomers, who lack the ability to negotiate and understand their new environment, though both try to figure it out as best as they can. I hope that someone is going to pick this serial up, because it's some of Simmons' finest work, with his near-psychedelic use of color in particular being a revelation.

In #21, Simmons also contributed a story called "Mutant", which is more what one would expect from him. Simmons quickly creates a strange scenario: a bunch of people standing outside somewhere at night. Someone gets beaten up, and a guy goes after the responsible party: a tiny demon with a plastic mask. After he stabs the demon to death with desperate gusto, he is told that it is now reborn, mutated and angry. Simmons has a way of generating dread and lingering doom like no one else; the specifics of the story and the reasons why anything are happening are important. What's important is that this guy who felt empowered and righteous one moment is irrevocably fucked, with his doom to come along at any moment. That's why he creates hands-down the most genuinely unsettling horror comics today.

T Edward Bak: These two issues offer the last part of chapter two and the first part of chapter three of his "Wild Man" serial about the explorer and scientist Georg Steller. They mark an interesting transition point in the story, as Bak goes from Steller in Europe with his fiance, passionately having sex with her as well as engaging in clever repartee with her; she is clearly his equal. Of course, the promises he makes to her are all doomed, as chapter three opens with a dream of sex turning into Steller having to deal with wild wolves in a near-Arctic setting. Bak really gets as the desperation and the human drama played out in the wild, the sense that there's no hope but trying to keep on living. A revised version of this story will soon be published by Floating World Comics.

Conor O'Keefe: Issue #20 debuted his new serial, "The Coconut Octopus". O'Keefe is a great example of an artist who really benefited from being part of Mome, as he refined his style noticeably over the past few years. I've come to enjoy his softly penciled and colored blend of Winsor McCay and Maurice Sendak, mixing whimsy and melancholy in equal measure. The titular octopus of the story is a very funny and cute figure, and I hope that O'Keefe can keep up this new story and the continuity of his characters elsewhere.

Nate Neal: Neal may not have the name recognition of some of the other Mome artists, but he was one of the most consistently interesting contributors during its run. "Magpie Inevitability" in #20 feels like a modern take on a Bob Dylan song from the 60s, with a cadence similar to "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)". Brightly drawn with a varied color palate, it's typical of Neal in that it focuses on how destructive modern culture is and the ways in which each individual is complicit in this emptiness. The combination really works well here, as the images balance out the stridency of the text. Neal has also been interested in the roots of language and how that ties into how we make images. "Cha-ul Nu Mon-Mon" in #21 is a beautiful, brutal story about a group of cave-dwellers. A young boy named Jani is taught by his mother ("Mon-Mon") how to paint on the walls of the cave; it's a thunderbolt of a moment for a young man who has found his destiny. His mother is young and beautiful and has drawn the jealous ire of her fellow wives of the chieftain; they use him in a plot to kill her. Flashing forward years later, Jani is the tribe recorder, painting another triumphant hunt by his father at his behest. When the story concludes with Jani sneaking off to draw a portrait of his mother, Neal gets at the heart of art's ability to bring to life what is gone and keep it alive forever.

Michael Jada & Derek Von Gieson: Their "Devil Doll" serial, mashing up hard-nosed WWII soldiers wandering into a potentially haunted town and finding madness, dragged in every single segment. Von Gieson is a talented artist, but his storytelling here is murky and difficult to follow, and the story feels bloated and tedious. I enjoyed Von Gieson's previous contributions to Mome, but this story just doesn't suit what he does best.

Steven Weissman: The comics veteran was a welcome addition to Mome, but his first entry in #20 was not what I expected from him. Sure, it was about kids and the ways in which they heap abuse on each other, but it quickly turned into a gruesome horror story with a number of wholly unexpected twists and turns. It's a must for fans of the artist, because he takes expectations and simply mangles them in a way that's emotionally powerful. The end was also unexpected in terms of both its plot twists and ultimate poignancy. #21 featured a number of his hilarious "Barack Hussein Obama" strips that would later go on to get their own collection. These strange and wonderful accounts of Obama and Joe Biden off on adventures, developing superpowers, and generally interacting as somewhat fractious best friends fits in perfectly with his Yikes! material, as the characters here are child-like in their demeanors and emotional states, and they balance that sense of cruelty and kindness that children can express at a moment's notice.Weissman's scratchy line and extensive use of effects like zip-a-tone add to the sense of fantastic, even if the figures are depicted more-or-less naturalistically.

Sergio Ponchione: Ponchione is another slightly odd fit for Mome, given the slightly goofy and bigfoot nature of these stories. That said, they look absolutely terrific in full color, coming on the heels of his excellent Ignatz line series Grotesque. #20 sees "The Grotesque Obsession of Professor Hackensack", a charming prequel to Grotesque. It's got the same manic energy that reflects Ponchione's interest in early American cartooning, with touches of Milt Gross and Rube Goldberg to be found. #21's "Sgnaz" channels Dr Seuss but also gets at the darker parts of the imagination that Ponchione is so fascinated with, especially those memories that are repressed but bubble up in unexpected ways. Without any hope for further Grotesque stories in English, it was a treat to see them in Mome, just like many of the foreign short stories that were translated and published.

Jeremy Tinder: It's a shame that Tinder hopped on to Mome so late in its run, because he really fit right in. "Time and Space" had this sort of Archer Prewitt quality to it that I enjoyed, as the main character was a sort of blobby figure seeking out satori and the ability to practice remote viewing. In a strip with lots of funny drawings and an absurd premise (he succeeds and joins his guru remotely on Mars, where they encounter the giant floating head of god and send out & receive good vibrations), its execution is done with deadly seriousness. There's no punchline, but rather a resolution to a problem posed earlier in the strip. That uncomfortable zone between the serious and the silly gives this strip a charge.

Aidan Koch: Koch's comics always have an elusive and slippery quality to them even as she provides all sorts of visual cues as to potential meanings. "Green House" in #20 is no exception, and its very title offers clues as to what's really going on. A woman brings a man over to her apartment, and he immediately puts the moves on her and they wind up having sex. He leaves early in the morning, and while she does not overtly comment on this, there's a moroseness in her body language that the reader can feel. The title refers directly to all of the plants she keeps in her apartment (which he comments on, baffled as to why she has so many); their growth is essential to her growth. When she offers to trade plants with a girl across the way, it's a way of creating a real connection, as Koch's drawings of the two of them sharing their plants together indicates. Indeed, that drawing has a shadowy circle surrounding them, as the two of them were in a flowerpot together. Having found a connection on her own terms, the guy calls her back, apologetic for leaving and wishing to get together soon; he'll have found her already blossomed. There are few artists who think through every line and its effects the way that Koch does.

Nicolas Mahler: I've always thought Mahler was kind of a curious fit for Mome; that European, cartoony bigfoot thing felt more like something that Kim Thompson would have put into an anthology, not Mome editor Eric Reynolds. However, his autobio short stories display a crackling, straight-ahead sense of humor that is unusual in Mome. "Convention Tension" and "Goodbye, Mr Nibs" in #20 deal with Mahler's experiences at comics shows and teaching, respectively. A cartoonist doing a strip about a con is not exactly a new idea, but I liked the way in which Mahler favorably compared comics nerds to art snobs ("at least the comics nerds have genuine despair going for them"). The second story speaks to the frustration Mahler felt with utterly disinterested students, a frustration that's heightened when a friend of his acts as a substitute for a class and has a great time. In #21's "Moving Pictures", Mahler first vents his spleen against an old art teacher and then goes into hilarious detail about how a government grant helped fund an animated project of his, talking about finding voices, finding an animator and being relentlessly hounded by the government for a final project -- including years after it was actually released! Mahler was never an essential part of Mome, but these shorts acted as an appealing palate cleanser.

Ted Stearn: There's not much more to say about Stearn's "The Moolah Tree" serial (which appeared in #20) other than it's funny, mean and impeccably drawn. It's a slow-moving serial that didn't seem to come close to finishing up by the end of Mome; indeed, it just seemed to get going. Stearn has a knack for making almost every character simultaneously lovable, completely stupid and dangerous to themselves and others.

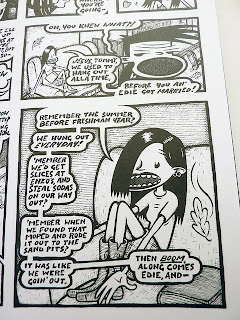

Kurt Wolfgang: Wolfgang is another MVP from Mome and is certainly one of the five cartoonists who made the greatest impact in the series. While his early entries in Mome were good, it was his "Nothing Eve" serial that really stands out. As we follow the protagonist of the story, Tommy, around the city on the last day before the end of the world, the reader knows he's trying to find his only real love, a girl named Edie. This chapter reveals that Tommy wasn't always the kindest person, as his reunion with an abandoned friend/fling named Patti reveals. Indeed, this portion of the story finds Tommy taking a hard look at himself for occasionally being a rotten friend. Wolfgang's drawing just gets better and better, mixing rubbery & stylized character designs in with heavy blacks and densely-crosshatched backgrounds.

Tom Kaczynski: Please see my review of "The Cozy Apocalypse" in my review of Kaczynski's collection of stories, Beta Testing The Apocalypse. Kaczynski was unquestionably one of the best and most productive cartoonists in Mome.

Jon Adams: Adams' delicately drawn and seriously strange strips have mixed naturalism and surreal, violent, nighmarish and cartoony imagery. "Almost Candied Chimera" is typical of his stories, involving a redneck father/son hunting duo, a whimsical creature, a violent death and a horrible fate.The silliness of the action is juxtaposed against the horror of what actually happens.

Nick Thorburn: Thorburn really plays to Reynolds' fondness for the gross, grotesque and silly. His crude strip about an alternate, even bawdier history of Benjamin Franklin deliberately riddled with as many lies as possible in #21 was very funny, revealing a strong influence from underground comics.His other strip was less funny than it was drawn in a lively matter. These strips were another nice palate-cleanser.

Lilli Carre': Carre's carefully designed and constructed figures point to her background in animation, but her stylizations always serve the neuroses, fears and wonders her characters encounter in her stories. In #21's "Marching Band", a woman wakes up one morning to hear a marching band pounding out a tune in her head that only she can hear. She eventually comes to accept this bit of madness until it disappears one day, which makes things even more maddening. Carre' gets at the common fear of being attacked or infested during one's sleep in an absurd way, and then makes a comment about the ways in which we internalize madness. It's a clever short for a cartoonist whose Mome entries were among the best the series had to offer.

No comments:

Post a Comment