This article was originally published at sequart.com in 2006.

************************

There's something particularly appealing about travel comics. Traveling involves beginning and ending points, making it easy to adapt as a narrative. By definition, travel stories almost always involve the narrator or protagonist doing something that's out of their ordinary frame of experience: they're in different settings and out of their daily routines. The eyes of a traveler are "new" eyes, observing something in their altered environment that a local might take for granted. Comics are especially well-suited for this because the artist can get across to the reader what a place looked like so much more effectively than with prose alone, yet can also modulate the degree to which they represent this realistically.

How the artist chooses to communicate what they've seen leads to choices that create some very different forms of what is essentially the same idea. O'Connor, the artist behind Journey Into Mohawk Country, is an illustrator of children's books who was fascinated by the travel journal of van den Bogaert, and he chose to flesh out those words with his own images. This journey into history was aided by extensive notes taken by the narrator, but the fact remains that this is an interpretation of an account of an experience, rather than a direct interpretation of the experience itself. Despite this, it's the most straightforward effort of the three authors cited here.

Mats!? chooses to make a first-person, anecdotal account of his experiences in Asia in Asiaddict. There isn't an actual narrative in sight, but rather an accumulation of observations, humorous asides and bits of weirdness. The result is both rollicking and reflective, respectful and smart-assed, morbid and mirthful. It's a playful book that manages to both give us a tour of the weird and disturbing in southeast Asia and provide a lot of practical advice for the off-the-beaten-path tourist.

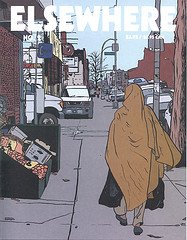

Gary Sullivan takes the most poetic and oblique route in his interpretation of what he saw in Japan and Coney Island Avenue in two separate issues of his minicomic Elsewhere. Though the panels flow by as in a conventional narrative, the words are either unconnected to the images but juxtaposed against them directly, or are a divination of the images. The experience of reading this is quite different than the other two books. Though it's a narrative of a sort, the way the text is arranged makes it more of a visual experience.

Journey is all about the Dutch expansion of beaver pelt trade with the Mohawk tribe, and van den Bogaert's journey north to hammer out a trade agreement. Along with two companions, he pays assorted tribe members to guide him north. The journey during the winter was not easy, and the story is one stop in Mohawk castles after another. The account is pretty dry even if the details are unusual; at one point, van den Bogaert tries to buy a tame bear from a local tribe. The Mohawks are constantly demanding that he shoot off his gun to celebrate deals that are made.

The fundamental difficulty I have with the book is that the text and illustration are often in conflict with each other. It's as though o'Connor can't quite shake the whimsical choices he might opt for as a children's book illustrator, and as a result the way he chose to draw the story makes it seem far more lighthearted than the text would indicate. While the outsider's glimpse into the minutiae of Mohawk life nicely depicted culture shock and a great deal of interesting historical detail, the overly cartoony art and occasional digressions into slapstick didn't work for me. The narrative was businesslike, often dry and bordered on desperate at times. The facial expressions o'Connor chose to emphasize (lots of wide eyes, slack jaws and crooked grins) were often at odds with what was going on in the text. Sometimes this sort of juxtaposition can be interesting, but over the course of an entire book it proved to be distracting. I think that's partly because o'Connor mostly plays it straight in the way he told his story. If he had gone a bit further into absurdism and/or a non-realistic depiction of the story, it may have been more effective. Those problems aside, Journey Into Mohawk Country was clearly a labor of love for an artist who had long been fascinated with the subject matter and an interesting experiment as a comic.

Asiaddict was the most compelling of the three offerings here. By concentrating on the most lurid, weird and overlooked details of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, Mats!? made every anecdote memorable. His visual style was a perfect fit for the tone of his observations: over-the-top, in-your-face and striking. There seems to be a bit of an EC comics influence at work here (especially the blood and guts that's prevalent at times), down to the bright and discordant use of color on some pages. While Mats' quieter observations (how to get around in Bangkok, tales of local writers, painters and architects, depictions of weird bric-a-brac) add a bit of quotidian weight to his meanderings, the real highlights come when he talks about the wilder sights.

That's best exemplified by his drawings and photos of the hard-to-believe "theme park" depicting Buddhist hell. That came complete with statues depicting torture, mutilation and other righteous punishments for the wicked. That is nicely balanced by his drawings and descriptions of ancient temples, both preserved and left to nature. When in Laos (the most-bombed country per capita, thanks to Nixon) and especially Cambodia, his humor becomes darker. Discussing the bloodthirsty idealogue Pol Pot, his subtitle is "Blood Brother Nr. One" as he discusses how the visions of one man led to the extermination of nearly a quarter of Cambodia's citizens. The most memorable tale he tells is of artist Vann Nath, a survivor of the most brutal prison in the country. He later went on to paint images of the torture he saw and experienced after Pol Pot was overthrown, as the prison was converted into a museum of genocide. Another vivid profile was of Akira, the "human mine sweeper". He's made it his life's goal to find every unexploded landmine in Cambodia, and maintains a small museum of his findings. The liveliness of Mats' exaggerated line combined with his wry observations made for an experience that was self-aware as to the author's own point of view while being completely unapologetic for that position. The result was a deeply satisfying read.

Sullivan's minicomics are quite a bit more abstract, yet still give a strong flavor of cultural clashes and information overload. Elsewhere #1 is his "Japanese Notebook", wherein he relays a variety of sights from his honeymoon in Japan. In particular, he depicts a number of advertising images, with accompanying garbled English phrases. The imagery shifts from traditional Japanese iconography to subtly warped Western depictions (usually in cartoon form) to the grotesque. The effect is distancing; unlike the other two comics noted in this review, there's no attempt at trying to make sense of what the narrator is seeing. Instead, Sullivan preserves the feeling of alienation and wonder that he experienced.

Similarly, Elsewhere #2 depicts similar phenomena even though this time the depiction was of a multi-ethnic street in Brooklyn. This time, the text is an adaptation of a poem about Coney Island Avenue, and Sullivan cleverly attaches the poem to the images he saw while walking up that same street. Unlike #1, which almost completely eschewed narrative in its use of text, #2's text seemed to flow from a beginning to an end. Of course, much of the text was a simple recitation of the sights and sounds from the street; much like in Japan, advertising was a central concern. In a densely populated city filled with populations and languages almost entirely unfamiliar to the observer, advertising is both bewildering and strangely comforting. Iconic depictions of things people want and need, and attempts to sell the same, are one thing that most people can understand. Yet their strangeness alters their context and meaning for the observer. That strangeness creates the poetic quality of the images and allows the text to follow suit.

Each comic plays around with different kinds of narrative styles, yet each one depicts a traveler on unfamiliar grounds. Whether that traveler is fully immersed (O'Connor), delivering omniscient commentary after the fact (Mats!?), or simply observing and processing pure information in offbeat ways (Sullivan) all three methods of storytelling rely on the fact that travel comics allow a creator to use a background that anyone can understand in order to experiment in other ways. Even if their intent is to depict adventure, humor or poetry, the tools are all the same.

No comments:

Post a Comment