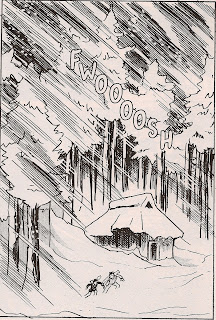

In 1956, at the tender age of 21, Yoshihiro Tatsumi was already a three-year manga veteran, having drawn 17 volumes and numerous short stories. As depicted in his memoir A Drifting Life, he was inspired by the novel The Count of Monte Cristo to create a prison escape yarn. Always driven to innovate and experiment, the young man blasted out the prison escape thriller Black Blizzard in a mere twenty days, a spate of creativity that saw him write and draw six pages a day! It was unlike anything that had been produced by a Japanese artist, though its hard-boiled story will seem familiar to modern audiences. The book really does look like it poured out of Tatsumi's pen, even as he came up with interesting formal tricks on the fly. For example, as Tatsumi's brother points out, a large portion of the story is dominated by diagonal lines, so as to represent the titular blinding snowstorm. It's all part of what Tatsumi does best in this story: create atmosphere.

The story involves a hard-boiled cardshark and a pianist framed for murder traveling under police supervision on a train. When the train derails, the pair, handcuffed together, flees the scene. Tatsumi creates a tense atmosphere for the duo, with howling winds, unrelenting police searches and their own distrust of each other. The card shark eventually declares that they'll never get anywhere bound together and pressures the pianist to chop off his hand. When he naturally refuses, this becomes a running conflict that is set on hold temporarily when they try to escape their pursuers but later picked up again in earnest. If Tatsumi makes a mistake as a storyteller here, it's the way he has the pianist artlessly talk about his backstory, wherein he fell in love with a circus singer and was subsequently given the brush off by the man who claimed to be her father--the ringmaster. While Tatsumi makes it pretty obvious who the real killer is, he throws another curveball at readers that's quite clever, redeeming the long flashback in the middle of the otherwise tense narrative. The concluding scenes are genuinely gripping, with all sorts of interesting twists and turns.

Tatsumi's formal tricks are interesting, even if they all seem familiar today. Still, they fit seamlessly in with the narrative, with every technique serving the story and the atmosphere he creates. At this point of his career, his grasp of anatomy was rudimentary at best, giving a number of pages a cartoony quality that he was unlikely trying to convey. As a result, his figure drawing is a bit on the melodramatic side as he really tries to sell the book's uneasy showdown scenes. At the same time, his understanding of body language and how figures relate to each other was already quite strong, giving these scenes their true power. The overall result is something every bit as good as a contemporary EC comics potboiler (in terms of the writing and formal innovations), which is pretty astounding when one considers Tatsumi's age and the fact that he was making it up as he went along. Tatsumi described the feeling of doing this book as the cartoonist's equivalent of the "runner's high"; at a certain point, things like fatigue fell away for a sensation of pure joy in the sheer act of putting pen to paper. While lacking the thematic sophistication of his later comics, Black Blizzard is a fine genre comic that delivers thrills and pathos in equal measure.

No comments:

Post a Comment