The second issue of Kristen Shull and Emily Zea's Fantology arrived just under the gun for inclusion in this feature. Unsurprisingly, this issue was generally superior to the first, often in surprising ways. For editors figuring out how best to assemble an anthology, the second issue is the one where all the kinks are generally hammered out in terms of process and production. In an anthology where very little is at stake in terms of money but a lot is at stake in terms of editorial credibility, young editors have to take risks on the kind of work they accept. There were a few newcomers in this issue and the returns were fairly positive on them; indeed, some of these stories were the best in the whole volume.

One of the more surprising and delightful aspects of this volume is that the shared-world conceit of the first volume not only carried over here, but that some artists used the creations of other artists from the first volume to strong effect. This is another similarity to the Cartozia Tales series edited by Isaac Cates, only without the OuBaPo-style rigidity with regard to rules and switching every issue. This felt like a relaxed and fun one for artists to play together in the same world. Speaking of relaxed, the issue's theme of "Flora & Fauna" struck a nice balance between having no theme and having one that produced too much of the same thing. Each artist was simply compelled to come up with a new animal or plant during the course of their story. Some of them were incidental, and some of them drove the plot.

While fantasy stories often devolve into world-building exercises, it was clear that Fantology's artists were generally far more interested in character-building. The characters drove the plots, and in the cases where they were returning characters, the stories served to expand on their histories and personalities. All of this is also tightened up by the anthology's narrator and gimmick Bartlebee the Bard, who not only informed the readers as to the anthology's theme, but also introduced each story and served as a natural piece of interstitial material. Unfortunately, one thing that got by the editors was matching up page numbers and the table of contents, which only had a passing resemblance to each other for many entries.

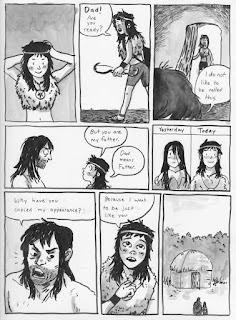

The continuing adventures of several characters were certainly highlights. Shull's own saga of Sabi and Kata (the elf and the wizard) once again had an episode that was not only entirely satisfying on its own merits but also moved along the larger plot. It even hooked in a character from a group introduced by Leise Hook in the first issue. Given that the main characteristic of the character was his lusciousness, this was right up Shull's alley. Catalina Rufin's continuing adventures of Brono and Satu, the barbarian and his child, continued to be pitch-perfect. While retaining a rough fantasy aesthetic, the gentle quality of the story belied its concept. Filipa Estrela's gentle saga of Frill and Frond, the mushroom person and goblin who became partners in the first issue, is expanded here as the parameters and boundaries of their relationship are tested. Indeed, this is less a fantasy comic than it is a comic about relationships with fantasy trappings, although Estrela made those trappings delightful. Emily Zea's "Troubled Waters" continues the adventures of Princess Trudy and pirate captain Troub. It's a funny and compelling story, as it's made clear that Troub is more closely connected to Trudy than she first let on. Zea's linework here seems considerably more rushed in this issue than the first, however. Alex Washburn's story about a group of dysfunctional explorers maintained its humor thanks to Washburn's thick line and irreverent storytelling.

The most interesting artists that were new to me were Tao Tao Jones and Chelsi Fiore. The former wrote a compelling story about the Pea from the "Princess and the Pea" becoming a cherished heirloom to a family of servants, until one of them broke away and created her own country based around the pea's growth. Jones' line is thin and scribbly, which suits the material, although I found myself wishing her script was a bit larger. Fiore's story about a desert traveler encountering a fuzzy little potato-like animal was imaginatively drawn and worked well with its short length. It was not just a story about reuniting a child with their family but also about an explorer who respected the environment they traveled in.

This anthology was filled with pleasant interactions in this particular world, proving that not every fantasy story has to be about conflict. Eddie O'Neill and Kay Brand told a story about a couple going hunting for eggs and herbs so they could have brunch together; the plot was thin, but it was all about fleshing out their dynamic as a couple. Emily Bradfield's story had a little more action, but it was about a witch and a new witch wishing to be her friend and work comrade and how routine can often prevent us from making connections. Rainer Kannenstine's story is a send-up of boastful fantasy tropes. Kat Ghastly offered up more of a psychedelic bit of lore than a story, but it worked as a visually impactful opener.

There were three stories that particularly stood out. Keren Katz's detailing of how the coin-people introduced in the first issue reversed their process and undid everything that was purchased with them was both conceptually fascinating and heart-rending. In terms of style, there's no one who draws with her level of detail and conceptual power. Kevin Fitzpatrick's meaty story about a potions-master and his imprisonment was full of fascinating character details, ethically thorny dilemmas, and extensive mastery of light and dark contacts. Emil Wilson's story about hunters discovering a bear with an orange tree growing on it not only had an exciting blend of naturalism and weirdness, it also was emotionally complex and touching.

At 252 pages, the volume felt a little bloated. There were several stories that were had to parse or process visually that could have been eliminated. While the slighter stories were enjoyable, this issue felt unbalanced in that direction. The more complex stories really stood out in this volume, but their tone was subdued by the lighter fare in some of the other stories. Creating a balance in an open-call anthology is extremely difficult, but it's a credit to Shull and Zea that they were able to sequence things in such a way that they were nearly able to pull it off.