Aaron Lange's talent is far-reaching, especially as a draftsman. He can work convincingly in any style, though he's a humorist at heart. Despite reaching out for pornographic and "edgy" punchlines at times, he really is just a solid gag man underneath it all. Lange is more than that, however. He's a take-no-prisoners autobio artist who's willing to look at his worst excesses, past and present, and portray them in an unflinching manner. All that said, I think his greatest strength is as a biographer. He has a way of taking even the most unsympathetic or difficult figures and laying their humanity bare for the reader, generating respect if not affection for them. Lange is an excellent writer and gets at the heart of events and achievements while never losing sight of the underlying and often tortured humanity of his subjects.

His Cash Grab series of minis is a perfect sampler of Lange's interests, plucked from sketchbooks and older publications. Issue #7 is a sketchbook sampler, mixing in gags, brief biographical comics and portrait sketches. A page about a high school friend who just passed away absolutely nails his bemused sense of curiosity, and the text Lange wrote about him is detailed without being too florid. Then Lange turned around with a gag titled "MK-Ultraman," combining the Japanese character with the CIA mind-control program. Then there's a study on logos and rides from an amusement park from his youth in Ohio, combining quotes from Sherwood Anderson and his own childhood recollections. There's a joke about a public service announcement-style character named "Cis" which is funny because Lange keeps piling on details, and that's followed by a drawing and brief bio of the actress Kari Wuhrer. There's a savage comics parody involving Emil Ferris and Ed Piskor, followed by a loving portrait of Lange's wife Valerie. Lange looked like he was channeling Gene Colan a bit there. This is a great introduction to Lange's general interests, and his use of color adds a lot of depth to his drawings.

Cash Grab #8 is all black and white, and Lange labels it as a "Deep Cuts" issue. There's a fascinating story he titled "The Aesthetics Of Grief" about the public appearances of Nick Cave and Susie Bick after their son Arthur died. It's about how they maintained their sense of style even in the face of grief because that's simply part of who they are. Later, he talks about his own alcoholism and how he wished at times the decision to stop would be someone else's, like a doctor. A note regarding his comics in general: Lange is one of the best letterers in all of comics. He is adept at using multiple, personal fonts, line weights and spaces between letters to create a number of different effects and add to the mood of each piece. His portraiture is truly superb, with his drawing of comedian Janeane Garafolo being a case in point. Using key squiggles, lighting effects, hatching, and some spotted blacks, Lange breathes life into a drawing that goes way beyond the photo reference he used for it. Most of the rest of the issue is devoted to portraits of comic book figures and characters from the film Boogie Nights. Lange could make a career out of these portraits in the way that Drew Friedman does; Lange is almost as good at it as Friedman is.

Issue #9 is in his wheelhouse, as it's most gags and stories about the world of porn. Instead of simply doing porno gags, Lange does a series called "Porn Stars I Like." He provides biographical data, quotes, and reasons why he likes them in descriptive and almost poetic terms. Those pages are interspersed with drawings of cats "speaking out" about various topics, as well as collages of porn images with jarring effects. It's a voyage through Lange's id, to be sure, but it feels honest instead of glib. Some of the images (like of a random asshole) are odd, to be sure, but fit into what he's doing in this comic. It's less titillating than it is raw and honest, and he counterbalances exploitation with exploration and humanization of his subjects. To be sure, Lange still attempts to be transgressive at times, with mixed results, but his increasing level of craft as a writer is what's taking him to the next level as a cartoonist.

This is the blog of comics critic Rob Clough. I have writings elsewhere at SOLRAD.co, TCJ.com and a bunch more. I read and review everything sent to me eventually, especially minicomics. My address is: Rob Clough 881 Martin Luther King Junior King Blvd Apt 10 i Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Thursday, February 28, 2019

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

Minis: By Mom, By Me

By Mom, By Me Volume 2: Tales From Our Early Twenties has an absolutely ingenious central conceit: artist Rachel Scheer adapts an autobiographical vignette from her mother Karen and then does a story of her own based on the same topic. For example, the mini begins with the topic "My First Apartment After College." For Karen, that was in Atlanta in 1973, and there were all sorts of interesting events that happened around getting that apartment. When she and her friend arrived, they went over to the offices of the local underground newspaper for advice and got a place in a drug-riddled area. Rachel then followed up with her own story in 2006 near Washington, D.C.

Each vignette is two pages, four panels per page. Scheer is clearly still finding her footing as an artist, as some of the drawings in the panels looked a bit clunky. It's not unusual for a young artist when they're trying to find the happy medium between naturalism and their own style. That said, Scheer is an excellent storyteller and knows how to create a striking image. She favors a single image that works in tandem with the text over traditional panel-to-panel transitions, and it's a technique that successfully gets across a great deal of information in a small amount of space.

Other topics include "traveling in college" and "something I'll never do again." For Karen, it was hitchhiking. For Rachel, it was smoking pot at Rehobeth Beach. There's a wonderful sense of connection between mother and daughter, as both clearly had a lot of freedom to make their own choices. It is subtly implied that this freedom is part of what bonds her to this mother. That's not just because of the collaboration (although that's part of it), but it's hinted in other ways, like when Rachel mentions moving back in with her mom after college for a while. This is a relatively brief mini, but I could have read a book full of these gentle, funny stories.

Each vignette is two pages, four panels per page. Scheer is clearly still finding her footing as an artist, as some of the drawings in the panels looked a bit clunky. It's not unusual for a young artist when they're trying to find the happy medium between naturalism and their own style. That said, Scheer is an excellent storyteller and knows how to create a striking image. She favors a single image that works in tandem with the text over traditional panel-to-panel transitions, and it's a technique that successfully gets across a great deal of information in a small amount of space.

Other topics include "traveling in college" and "something I'll never do again." For Karen, it was hitchhiking. For Rachel, it was smoking pot at Rehobeth Beach. There's a wonderful sense of connection between mother and daughter, as both clearly had a lot of freedom to make their own choices. It is subtly implied that this freedom is part of what bonds her to this mother. That's not just because of the collaboration (although that's part of it), but it's hinted in other ways, like when Rachel mentions moving back in with her mom after college for a while. This is a relatively brief mini, but I could have read a book full of these gentle, funny stories.

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Minis: Forever and Everything #3

Forever and Everything #3, by Kyle Bravo. This is more autobio work from an artist who previously just went by "Kyle." Bravo uses a simple, stripped-down line not unlike Kevin Budnik, emphasizing character expressiveness above all else. Bravo's line weights don't vary much, nor does he add much in the way of effects like spotting blacks, hatching or shading of any kind. He's fully committed to a 12-panel grid and keeps it simple as a way to keep his vignettes briskly moving. The captioned titles for his vignettes are very much in the style of a Jeffrey Brown, who is another clear influence.

There's a sweetness to these strips as Bravo writes about daily life with his son Ollie and his wife Penny. The strips with his toddler son are excellent, as Bravo's joining a growing number of cartoonists who express the day-to-day joys and frustrations of raising a child in a realistic way. The extreme mood swings of children as they are developing can be frustrating, but Bravo keeps it in perspective as he documents it. Bravo also documents the new pregnancy of his wife in a poignant manner, acknowledging the fear that can be a part of early pregnancy when miscarriage can occur. One thing I liked about this comic is that Bravo treats it as a sort of document regarding his self-improvement as a person and artist. He struggles with how to address the subject of his parents, with whom he had some unresolved issues. He takes a writing class to improve in that area. He's constantly working and puttering to improve his New Orleans home. He goes to therapy and tries to process the trauma of hurricanes.

Finding ways to cope is a constant theme in his work. For example, after a positive experience at SPX, he still found himself overwhelmed by a weekend of intense stimulus. So he walked to a church service on the Sunday after the show, finding a way to clear his mind. This particular issue ends with the birth of their second child, as they take their time trying to figure out a name for her. That whole sequence is both amusing and slightly poignant, as his wife in particular struggles to settle on something, even after they've officially recorded the name. It's all part of the gentle quality of this comic, as Bravo navigates conflict with grace and honesty. Bravo approaches amusing quotidian moments with his family with the same quiet directness as he does bigger emotional issues, and it's that even-handed narrative quality that lends the comic its charm. Bravo has a strong storytelling sense, giving even the smallest moments a rock-steady framework that entertains on a beat-for-beat basis, especially as he intentionally runs each moment together on the page. That results in a reading experience that feels fresh on page after page, despite the fact that his visual and emotional narrative structure never varies.

There's a sweetness to these strips as Bravo writes about daily life with his son Ollie and his wife Penny. The strips with his toddler son are excellent, as Bravo's joining a growing number of cartoonists who express the day-to-day joys and frustrations of raising a child in a realistic way. The extreme mood swings of children as they are developing can be frustrating, but Bravo keeps it in perspective as he documents it. Bravo also documents the new pregnancy of his wife in a poignant manner, acknowledging the fear that can be a part of early pregnancy when miscarriage can occur. One thing I liked about this comic is that Bravo treats it as a sort of document regarding his self-improvement as a person and artist. He struggles with how to address the subject of his parents, with whom he had some unresolved issues. He takes a writing class to improve in that area. He's constantly working and puttering to improve his New Orleans home. He goes to therapy and tries to process the trauma of hurricanes.

Finding ways to cope is a constant theme in his work. For example, after a positive experience at SPX, he still found himself overwhelmed by a weekend of intense stimulus. So he walked to a church service on the Sunday after the show, finding a way to clear his mind. This particular issue ends with the birth of their second child, as they take their time trying to figure out a name for her. That whole sequence is both amusing and slightly poignant, as his wife in particular struggles to settle on something, even after they've officially recorded the name. It's all part of the gentle quality of this comic, as Bravo navigates conflict with grace and honesty. Bravo approaches amusing quotidian moments with his family with the same quiet directness as he does bigger emotional issues, and it's that even-handed narrative quality that lends the comic its charm. Bravo has a strong storytelling sense, giving even the smallest moments a rock-steady framework that entertains on a beat-for-beat basis, especially as he intentionally runs each moment together on the page. That results in a reading experience that feels fresh on page after page, despite the fact that his visual and emotional narrative structure never varies.

Monday, February 25, 2019

Minis: 100 Life Hacks & Life Hacks 2

These aren't really comics for the most part. Rather, they're crudely-drawn illustrations with lots of jokes regarding the subject: humorous "life-hacks." I've noted in the past that illustration and cartooning are two related but different disciplines, particularly when I'm looking at a crudely-drawn comic that is nonetheless rock-solid in terms of design, character interaction, transitions, etc. In this case, the cartoonist (who just goes by "Ben") barely seems interested in cartooning. Many of the illustrations hardly have anything to do with the jokes. The jokes are typeset, with some pages just featuring a couple of dozen gags with one illustration.

Life Hacks 2 is better in that Ben at least shows more dedication to actually illustrating his jokes. There's a "paid advertising section" with gags like "Shaq Daniels" as the label on a bottle of bourbon. Ben's sense of humor ranges from the absurd to low-hanging fruit like scatological humor, with the former being funnier than the latter in terms of structure and thought. Ben did a kickstarter for this project and so crammed each issue with as much extra material as possible, though the effect was to prolong a comic that didn't have much substance to begin with. There's a guest gag panel by Meghan Turbitt, an artist who uses a similarly crude style. In her case, her commitment to the drawing has always been primary, and it shows in her gag here about an extra long straw. It also looks like Ben is drawing a basic computer program and coloring it the same way. The result is not just something crude but also something lifeless on the page. Ben is unquestionably funny, but these comics speak to his need to rethink his approach and even if he wants to make comics.

Life Hacks 2 is better in that Ben at least shows more dedication to actually illustrating his jokes. There's a "paid advertising section" with gags like "Shaq Daniels" as the label on a bottle of bourbon. Ben's sense of humor ranges from the absurd to low-hanging fruit like scatological humor, with the former being funnier than the latter in terms of structure and thought. Ben did a kickstarter for this project and so crammed each issue with as much extra material as possible, though the effect was to prolong a comic that didn't have much substance to begin with. There's a guest gag panel by Meghan Turbitt, an artist who uses a similarly crude style. In her case, her commitment to the drawing has always been primary, and it shows in her gag here about an extra long straw. It also looks like Ben is drawing a basic computer program and coloring it the same way. The result is not just something crude but also something lifeless on the page. Ben is unquestionably funny, but these comics speak to his need to rethink his approach and even if he wants to make comics.

Friday, February 22, 2019

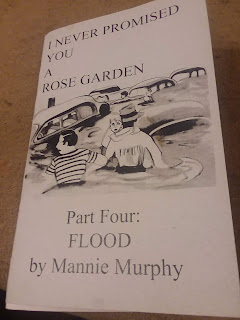

CCS Extra: Mannie Murphy

Mannie Murphy's continuing zine series I Never Promised You A Rose Garden has been a fascinating, essential read. It can be best described as a thorough, detailed history of Oregon (and Portland in particular) and its problematic, white supremacist roots. In light of the mainstream rise of white supremacist movements in the US since Murphy began the series, it's all the more instructive and important to read. This isn't so much a comic as it is an illustrated zine, but Murphy's handwritten approach (in cursive, even) gives the zine a high level of intimacy. It also helps that Murphy is simply an excellent writer, matching an evenhanded approach with a slow, simmering passion.

Issue #3 is titled "Hatemongers," and it's about Murphy watching a 1988 episode of the Geraldo Rivera show that featured a white nationalist riot. A chair was thrown and broke his nose, but what really threw Murphy was realizing that some of the people on the show were local to Portland. In fact, they were key figures in the second issue of the series. The show was a white nationalist blueprint: find an excuse for provocation and then engage in extreme, shocking violence. It's also proof positive that there is no such thing as civil, rational discourse with white nationalists. They have a particular worldview based around the paranoid belief that they are the real victims, and everything they do and say is defensible because of this. Giving them any kind of attention and allowing them to act out is giving fuel to the movement, emboldening violence and even murder. Circling back 'round to Portland (and other police departments), such activities often go unpunished or even encouraged and sometimes propagated by the very police departments that are supposed to protect its citizens.

Issue #4, "Flood," is an account of an attack by local Cayuse native Americans on the settlement in what would become Portland. It was retaliation for the flood of white settlers intentionally bringing in disease in order to wipe out the natives. They also poisoned native food in an effort to bring about genocide, rather than try to convert the Cayuse. This was all part of establishing Oregon as a "white utopia," and it continued with laws specifically forbidding black people from staying in Oregon or Asians from emigrating there. Murphy carefully provides primary evidence regarding the ways in which public officials were cozy with the Klan and then connects it with the Bundy family's absurd "siege." The titular "flood" in the title refers to a flood of white settlers, but it also refers to a literal flood that destroyed the shoddy housing of Vanport. That was a small black town that popped up thanks to a new for labor in booming Portland, wiped out by a flood. Those black citizens trying to relocate were forced into a section called Albina, thanks to "white banks, realtors and homeowners systematically denying rights based on skin color."

Murphy notes that Albina became a tight-knit community that thrived in spite of its disadvantages, but capricious police murders of black citizens went largely unpunished. Even when officers were suspended or fired, the cops would assemble en masse to protest in a show of force, usually effecting the reinstatement of these cops. Even one police captain was reinstated after definitive links to Nazi groups were established. What Murphy does best is connect the dots: relentlessly, grimly, and with great precision. Terms like "white supremacy" aren't simply thrown around; they are grounded and documented with a powerful grip on history and the way it echoes and ripples down to the present. Murphy is also quick to note the history of resistance and resilience to oppression and is careful to document this resistance in as much detail as they do the sheer, naked brutality of white supremacy. This zine is a document of that history and is an act of resistance in the sense that it seeks to prevent revisionist history from obscuring the real truth of Oregon's history, as well as expose the real and obvious connections to the white supremacist scourge that is openly rearing its ugly head.

Issue #3 is titled "Hatemongers," and it's about Murphy watching a 1988 episode of the Geraldo Rivera show that featured a white nationalist riot. A chair was thrown and broke his nose, but what really threw Murphy was realizing that some of the people on the show were local to Portland. In fact, they were key figures in the second issue of the series. The show was a white nationalist blueprint: find an excuse for provocation and then engage in extreme, shocking violence. It's also proof positive that there is no such thing as civil, rational discourse with white nationalists. They have a particular worldview based around the paranoid belief that they are the real victims, and everything they do and say is defensible because of this. Giving them any kind of attention and allowing them to act out is giving fuel to the movement, emboldening violence and even murder. Circling back 'round to Portland (and other police departments), such activities often go unpunished or even encouraged and sometimes propagated by the very police departments that are supposed to protect its citizens.

Issue #4, "Flood," is an account of an attack by local Cayuse native Americans on the settlement in what would become Portland. It was retaliation for the flood of white settlers intentionally bringing in disease in order to wipe out the natives. They also poisoned native food in an effort to bring about genocide, rather than try to convert the Cayuse. This was all part of establishing Oregon as a "white utopia," and it continued with laws specifically forbidding black people from staying in Oregon or Asians from emigrating there. Murphy carefully provides primary evidence regarding the ways in which public officials were cozy with the Klan and then connects it with the Bundy family's absurd "siege." The titular "flood" in the title refers to a flood of white settlers, but it also refers to a literal flood that destroyed the shoddy housing of Vanport. That was a small black town that popped up thanks to a new for labor in booming Portland, wiped out by a flood. Those black citizens trying to relocate were forced into a section called Albina, thanks to "white banks, realtors and homeowners systematically denying rights based on skin color."

Murphy notes that Albina became a tight-knit community that thrived in spite of its disadvantages, but capricious police murders of black citizens went largely unpunished. Even when officers were suspended or fired, the cops would assemble en masse to protest in a show of force, usually effecting the reinstatement of these cops. Even one police captain was reinstated after definitive links to Nazi groups were established. What Murphy does best is connect the dots: relentlessly, grimly, and with great precision. Terms like "white supremacy" aren't simply thrown around; they are grounded and documented with a powerful grip on history and the way it echoes and ripples down to the present. Murphy is also quick to note the history of resistance and resilience to oppression and is careful to document this resistance in as much detail as they do the sheer, naked brutality of white supremacy. This zine is a document of that history and is an act of resistance in the sense that it seeks to prevent revisionist history from obscuring the real truth of Oregon's history, as well as expose the real and obvious connections to the white supremacist scourge that is openly rearing its ugly head.