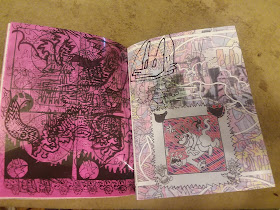

Aaron Cockle's meditation on work, capitalism and the merging of personal and work spaces is a comic called Over Time, Every Section Had Been Allowed To Grow Accordingly. The second issue collects four more stories in this quiet but nightmarish scenario. "Walks Through Untended Orchard" is unusual because it's all figure and illustration work by Cockle (albeit with day-glo colors provided by a Risograph). Most of his strips tend to be collages of a sort or at the very least filled with text. Instead, this is a quiet moment away from everything. There's no work, no information other than the apple tree and the apple. The onomatopoeia of the "crunch" filling up an entire page is crucial, because the whole trip is an appeal to the sense unhindered by technology or the structure of work.

"Dream Sequence" is about the concessions one makes while trying to create art in a world driven by money. A team of two is filming a bootleg horror film until a "weather event" sweeps them away with a sense of almost calming inevitability. Here, everything is taken away from two people trying to work under the radar, with their impending bad end being so obvious that it's almost welcome with a smile. "Emperor Panorama" is a text/photography cut-up, mixing two different strains of text about time and place with photos bled through with a single spot color. "Anxiety Of Isolation" is the most disturbing of these stories, as it's about night shifts, loneliness and disconnection.

Andalusian Dog is a new series from Cockle, and I've read the first four issues so far. It's about a man who has a video game named after the famous Surrealist film by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali. Unlike that film, which was made purely on whatever images they could think of in an effort to shock and jar the viewer with dream logic, Cockle is crafting a narrative based on paranoid logic built on hidden knowledge. The first issue finds the narrator kicked out of an apartment for mysterious reasons, but he takes the Andalusian Dog video game with him. Turns out the game is a reality emulator and creator; it can recreate spaces that it's been in long enough. The second issue ties the video game into a wider, byzantine secret society/cult surrounding versions of the game that predated the video game. Immortality, arcane knowledge and fever dream logic are all part of it as Cockle alternates text and image in the 2 x 3 panel grid on each page. It has the rhythm of a game, just as the open-page layouts of the first issue felt more like floating through free, virtual space.

The third issue is a sort of take-off on the idea of terms and conditions for owning the game, only the punishments for violating them are hilariously severe. Exile, banishment, public and private humiliation are all on the table, as the harsh text illustrates crudely-drawn diagrams. The final issue is giant block printing over old office photos; the text is frequently and deliberately obscured by the images to create dissonance and discomfort, mimicking the experience of being trapped in an office. Once again, Cockle's goal is to destabilize one's idea about corporate culture and capitalism in general by treating it as a kind of incubator of madness, a sinister form of feng shui. The game may be a key to subverting it, or it may be part of what creates it; Cockle leaves this vague. As always, his ideas discomfit the reader in a calculated but often whimsical fashion.

This is the blog of comics critic Rob Clough. I have writings elsewhere at SOLRAD.co, TCJ.com and a bunch more. I read and review everything sent to me eventually, especially minicomics. My address is: Rob Clough 881 Martin Luther King Junior King Blvd Apt 10 i Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Monday, December 31, 2018

Sunday, December 30, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #30: Reilly Hadden

Reilly Hadden is one of the most

prolific and talented CCS grads, and in his case, his sheer work

ethic and willingness to follow his ideas to some strange places have

made him a better cartoonist. His regular anthology series Astral

Birth Canal is up to twelve issues, and he has several different

side projects he's working on as well. His comics are smart, funny,

fearless, strange, horrifying, bleak and humane. He's moved way past

his influences at this point to create his own strange aesthetic,

intermingling fantasy violence and moment-to-moment personal details.

Krikkit On The Creek is the

second of his minis to feature this gentle cat character. It's a

small mini that has no real plot: it simply follows Krikkit as he

explores his environment in a mindful, happy manner. Every moment he

spends walking around the creek and its accompanying waterfall,

fields, stone bridge and cave is a happy one. He's delighted to eat

from a blueberry bush and observe lobsters, ostriches and a new.

Hadden offers spot color using colored pencil for Krikkit, making him

a light orange that contrasts nicely with the simple black and white

renderings. Like anyone doing a comic for young children, Hadden

makes the comic a series of lists of things: things seen, things

eaten, things interacted with. It's a delightful little object.

His series Kath starts with a

standard Hadden technique: beginning a story in media res and then

slowly filling in the backstory as the action propels the narrative

forward. The comic starts with the titular character eating a

sandwich by a fire, before she's interrupted by an imp. Their

interactions lead to a monster sent by the gods coming to destroy

her, a conflict that plays out with him defeating him just long

enough to get away. Kath is a marvel of character design: her stringy

hair, scarred face and battle-hardened body only become more

interesting to look at when she dons her huge, horned helmet. In the

third issue, we learn her quest, see her take a tough moral stand and

make a daring, clever escape. There's an admirable

straightforwardness to this comic that Reilly sometimes eschews in

his work, and he accomplishes the neat trick of laying down narrative

pipe while keeping the action going at the same time. Every reveal

leads to the next big action, as the story comes into greater focus

even as Hadden keeps increasing the stakes. The quest of looking for

her child and bonding with her son's memory by eating the sandwich

they invented together adds a level of humane sweetness to the

proceedings.

Finch Island #4 is the

continuation of yet another series, involving an anthropomorphic bird

paddling to an island founded by an ancestor. We also see him from

another point in time, his story commented on by a pair of frogs who

happen to be traders. This comic is a model of restraint and tensions

literally roiling beneath the surface, as Hadden masterfully reveals

in the water as Finch is leisurely bringing his boat ashore. There

are monsters, underwater societies and other bits of oddness rendered

in a light hand, giving the impression that the reader can only

barely make out what's there. Considering the rest of the issue is

Finch exploring the island with a dog that he rescued, and one comes

away with a weird tension that something's about to happen, but it's

not clear what that might be. There's an almost poetic feeling to

some of the sequences in the book, particularly the still ones where

Finch is just stargazing.

Finally, there's the interlocking

Astral Birth Canal #10-12. This series is still Hadden's best

work, and it's his own mad science laboratory for exploring

long-form, improvisational storytelling. Hadden loves pushing new

ideas and images on his readers and letting them figure things out on

their own. He's wrapping up this title in favor of a new one to be

called Astral Forest, and it's a split that makes sense in the same

way his nearest comparison in comics, Chuck Forsman, did when he

ended his Snake Oil series. Both of these series explored fantasy

tropes in unusual contexts with weird, often absurd humor in the face

of horror. For all his flourishes, Hadden never strays too far from

creating a traditional narrative here, only mediated by his own

sensibilities and desire to keep things from getting too calcified

and safe.

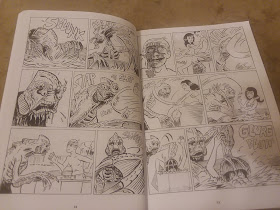

The bulk of the narrative here concerns

Edward, son of Bork, who is a space god often sent on missions to

eliminate certain horrible people and monsters. Bork is dead and

Edward's just been killed, but they are watching lives playing out in

an effort for Edward to learn more about his mother Valentina. She's

a pro wrestler whose career takes off when she falls in love with

Bork. With key songs in the background amplifying the action, Hadden

takes the reader out of the story to remind them that other people

are watching this, including Edward's horrified reaction to seeing

his parents have sex. #11 has Bork's reveal that he's a god after he

helps her win the wrestling championship, and she offers to come with

him. Hadden interjects tons of humor in Bork's awkwardness, the way

the wrestlers are drawn, and the horribly embarrassing moments

involving sex that alarm his son. #12 has an escaped prisoner that

Bork captured on his ship wreaking havoc, ending up with a shocking

cliffhanger ending that reveals not all is as it seems. He then added

tremendous depth to this storyline, with the sweet and bizarre

relationship between Bjork and Valentina on display and told with

complete sincerity and a surprisingly heavy erotic charge.

The back-up stories as strong, as

Hadden continues to find a host of interesting artists to work with

for back-up features. Cooper Whittlesey's dense story is told through

a nine-panel-grid, each page upping the ante of danger for its main

character. Steve Bissette draws a forest monster, while Anna

McGlynn's choose-your-own-adventure comic for her main character is

clever, as it comes up with a cosmogony for a primitive society using

yes/no questions. It's enjoyable to explore major events disrupting

such societies in this way, as these disruptions often lead to

significant long-term changes. Audry Basch's peek at a couple of dog

superheroes, Hadden & Susan Dibble's delightful fairy tale about

lovers, and Iona Fox's over-the-top story showing Val and Bork having

sex are less impactful but still add a lot of depth to this

world-building process. We're learning about how and way many of

the characters do what they do and why.

I suspect Hadden's new series will be

another leap forward for him, allowing him to tell some new stories

while still dabbling in this world he's created. It's a world where

anything can happen, the powerful are merciless, and hope is still

present albeit way in the background. His cartooning is confident,

his understanding of narrative is sharp, and his approach

continuously explores the idea of gender and gender roles in

fascinating ways.

Saturday, December 29, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #29: Ocean Jones, Bread Tarleton, and Kevin Reilly

Jones' own Big Jumps 1 is very much in the vein of Big Grungus, only these are personal observations. That scrawled, expressive line and warped perspective fills every page as they talk about wanting to personally transform their body, piss on the government, and try to get up. Tarleton's The Woods is different: it's a silent work about a small person traversing their way through some thick, mysterious forest land. Tarleton's line here is dense, with lots of gray shading and cross-hatching. When the traveler sees a series of bug-like creatures marching in a row and then sees one of them devoured from above by a monstrous creature, they decide to leave the same way them came from. It's a strong sequence that manages to convey emotion through some subtle use of body language, and the visceral surprises in the story sell the reader on that shock.

I reviewed Mothball 88 earlier in December, but I have a few other Kevin Reilly comics to consider. Reilly's collection of short stories,

Obscure Imperatives, sees him working in a number of different

genres and styles. “The Birthplace Of Saints” is a story that

sees him working through a number of different influences, yet coming

out with a style all his own. It's been noted that his thin, wispy

line is reminiscent of CF's, but I see more of Olivier Schrauwen (in

terms of color and forms) and Dash Shaw (in terms of the fantasy)

content here. That said, this story of a roller-skating keeper of the

faith who protects a temple important to pilgrims is entirely its own

thing. Reilly has a knack for not just world-building, but creating

entire ontological systems for his characters. The way he has the

belief systems attached to his worlds play out over the course of the

narrative is fascinating, especially since so many of them wind up

being horrific or lethal in some way. The way he ties those systems

into sports and competitions is also interesting, as

self-actualization as a believer is directly tied into one's own

athletic prowess.

There's a little Mat Brinkman in his

“The Obscure Imperative”, a quest story with tiny panels,

unusually shaped figures, and a starkly steady line weight. Again,

Reilly's stories play out as narratives with a lot of stake, and in

this case it's survival and memory. He creates a set of rules, lets

the reader know just enough to follow the story, and then takes those

rules to their logical (and frequently disquieting) end. “Fifteen”

is an unusual mix of genres. It starts as a teen romance, with a

mysterious girl named Molly encouraging the narrator to run away with

her. She's too cool for him, but she gives him a mix tape that may

have magical effects. There's a steadiness to his line here that is

unchanged despite the frequent and weird scene changes, where the

narrator goes from chasing her to becoming a member of a marauding,

anthropomorphic rock band to fodder at a mental institution to

running free.

A Thousand Times is Reilly's

take on the Ed Emberley assignment, where an artist draws a story

using the simplest of geometric shapes. It's the story of a horse

that keeps running and running, trying to find its girdle. It's

another example of Reilly creating a world with its own dream logic

that inexorably leads to a horrific end. Halcyon Bike Shop is a piece

of cleverly-designed commercial work that doubles as a guide for how

to maintain one's bicycle and an advertisement for the shop itself.

It's beautifully constructed and designed, and it points out a

constant in Reilly's work: absolute clarity in his storytelling. It's

obvious that he has a big future ahead of him as a cartoonist,

especially if he finds a publisher that believes in his work.

Friday, December 28, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #28: Rainer Kannenstine

It's a special privilege to see the

entirety of a CCS student's thesis package, as I noted when I

reviewed Dan Nott's comics. CCS students are taught to emphasize

format and presentation alongside content. In terms of the former,

Rainer Kannenstine's thesis was a one of a kind. It's not unheard of

for a thesis to be presented in a handmade box. However, gluing

nearly forth teeth to the side of said box, which has been

criss-crossed with electrical tape, is something I've never seen

before. It made it feel as though I was about to peer into a

forbidden tome of some kind, literature that's dangerous.

The actual contents were much

friendlier than that, showing off a variety of different styles in a

bunch of narratively unconnected but thematically similar minicomics.

Kannenstine's future as a cartoonist lies in humor, as the best of

these comics were the funny ones. That said, the supernatural/sci-fi

aspects of many of these comics showed that he was fluent in a number

of different genres and cross-genres. His character design is strong

and no-nonsense, giving the reader an immediate sense of what each

character is about. There's also an immediacy to his work that

indicates an admirable level of spontaneity. His line is lively and

fluid. However, the trade-off there is that his work has many more

textual errors than I would expect in a final project. There were

times where I wasn't sure if this was part of a specific dialect

choice or if they were indeed errors, which took me out of the work.

Kannenstine clearly needed other eyes to proofread his comics.

This Sucks is a slightly revised

version of a comic that he did earlier, and it's still one of his

best. It involves a stressed-out young woman being chosen by a cosmic

being to help decide if her universe lives or dies. Kannenstine's use

of a thin line to establish the woman and her general ennui is then

subverted by sticking her in space, that line swallowed up by the

black void of space. The cosmic being is almost formless, other than

his cruel mouth and tuxedo. It's a nice, absurd touch. The end of the

story is both funny and horrible, yet entirely fitting—especially

since the woman is not actually rewarded for doing what she did.

Zapadoodle 1 and 2 are sketch

and process minicomics. The first one emphasizes linework, and one

can see him employing different line weights with the same material

as a way of generating different effects. Kannenstine's blobby

characters have a cartoonish charm that works well, like a pair of

cacti in a desert, a huge brute and a smaller creature considering

helping him, or his own self-caricature. He's also good at using

greyscale shading to interesting effect, but I think his future as a

cartoonist lies in further developing that loose, casual use of

shapes in creating figures. The Life of Ded makes that clear,

although the heavy line weight here is too dense in telling this

funny store about a ghost who reluctantly goes to a party. His

authorial voice is bold in that comic, however, and it further shows

his strengths in writing funny comics.

Nidhog is perhaps the

best-looking of his comics here. Kannenstine uses bold black and

white contrasts in telling the story of a woman and a demon, mixing

around time and perspective to get at their relationship. His

linework here is excellent, as he found a delicate balance between

using a thinner line weight without sacrificing the overall boldness

of the visuals. As the story goes on and the reader begins to

understand that the power dynamic between the two of them was not

what it appeared to be at first, the ending is all that much more

effective.

To My Dearest Johan is

indicative that Kannenstine used his thesis not so much to show that

he was a finished product as a cartoonist, but rather to demonstrate

a number of different kinds of storytelling approaches. This is a

strong drawing display about a child devouring himself, talking the

reader through how and why. It's whimsical and weird, much like most

of his output. Finally, Snakes is Kannenstine's most focused

and sustained narrative. It's about a spaceship containing the eggs

of the last remaining race in the universe not devoured by “the

Snakes”, and the relationship between the caretaker of the eggs and

his friend the robot. Kannenstine uses the slightly ragged line of

This Sucks, the sharp black and white contrasts of some of the

other comics, and a sweet sincerity that's not really present in his

other work. What kind of cartoonist is Kannenstine going to become?

Hopefully, it will be one who can draw on gleeful nihilism as well as

a genuine attempt at creating empathy for his characters. He's

clearly most comfortable with subverting genre work in frequently

humorous fashion, especially with regard to how he varies line

weights. Between Snakes, This Sucks and Nidhog, there's

a formula there for a longer work with memorable characters, funny

twists and a commitment to working within a genre to create emotional

content and surprises.

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #27: Denis St. John

Denis St. John balances both genuinely unsettling horror comics with a quirky sense of humor. The result are stories that unnerve or shock the reader while making them laugh. In his collection of short stories, The Land Of Many Monsters And Many More Monster Tails, St. John bounces between takes on familiar creatures with wildly original characters and also draws a lot of dinosaurs fighting. If it sounds like pure fun on each page, that's because it is. This is a case where an artist expresses themselves through genre work in unusual ways, taking delight in the ways in which he can provide warped versions of classic ideas.

For example, "Drought" is a story imagining what happens when a Creature from the Black Lagoon encounters a drought. St. John's stories thrive on their sense of logical consistency, especially with regard to how one thing leads to another. In this case, the Creature happens upon a group of wholesome teenagers in an big, raised pool. (That the teens bear a suspicious resemblance to a certain gang of pals 'n gals from Riverdale is nothing more than coincidence, I'm sure.) The poor creature just wants some water when one of the gang slaps him, resulting in the Creature retaliating by slashing his face open. It's a shocking but funny image, especially after the creature is baffled and pained by the chlorine in the pool's water. Things go downhill from there, as St. John subverts the Creature/beautiful woman trope in gleefully horrifying ways.

"Horns" and "King Of The Hill" are silent stories featuring dinosaurs, and they are written with wit and verve. The fact that St. John clearly delights in drawing these creatures goes a long way to making the stories lively and fluid. The action is clear, the motivations make sense, and the sense of resigned patience on the part of the apex predators is all part of the comedy. The lush backgrounds provide the needed atmosphere to give the story some context without impeding the action.

St. John's former anthology series was called Monsters and Girls, and that speaks to his love of featuring femmes fatale in a number of different roles. In this collection, "Magic In The Moonshine" is about a witch who doubles as a burlesque dancer during prohibition times, and the aesthetic is a tribute to the Max Fleischer cartoons of the time. She winds up dodging demons and bible-thumpers by dropping in on a bootlegger who had a crush on her, and the resulting story is sweet and trippy. St. John is at his absolute best here in dipping between drawing her as a sexy woman and as a pile of bones, and the "magic drink" hallucination sequences are a particular pleasure.

"Dance Of The She Beast/Redneck And The Wolves" speaks to a different kind of femme fatale and a far less discerning audience. It takes the trope of the woman/witch turning into a wolf in the woods and subverts the hunter as Good Guy in this role, with a shockingly visceral death scene that ironically underscores his claims of being a hero. The subsequent story continues his shaky narrative, but there are dire consequences for him as a result. His story starring "Furiosa Frankenstein" combines the Bride of that particular monster with the ass-kicking heroine of the recent Mad Max update. This story mixes horror with action, as she has to fight the creatures in front of her as well as an imagined, twisted version of herself back at the lab where she was born. The visceral quality of his drawings is at his most detailed here, as the monsters drip with menace and gore.

Finally, "Whispers In The Woods" and "The Devil's Magic" reflect St. John's interest in having the mundane confront the extraordinary. The former story is about a couple of friends who go back and forth between thinking they're in horrible danger and trying to disbelieve in it, with increasingly rising stakes. Their reactions to what they see are hilarious, especially as the images become more and more bizarre, disturbing and monstrous--but not all is as it seems. The latter story is a funny, silent story, as a demonic figure shows up at a little creature's birthday party to perform the most mundane of tricks, yet those tricks are more impressive than him appearing and disappearing in puffs of smoke. St. John's line here is thin and expressive, emphasizing the almost dainty quality of the goat-creature magician's hands. This is a strong collection that fans of classic horror and more recent comedy-horror will appreciate.

For example, "Drought" is a story imagining what happens when a Creature from the Black Lagoon encounters a drought. St. John's stories thrive on their sense of logical consistency, especially with regard to how one thing leads to another. In this case, the Creature happens upon a group of wholesome teenagers in an big, raised pool. (That the teens bear a suspicious resemblance to a certain gang of pals 'n gals from Riverdale is nothing more than coincidence, I'm sure.) The poor creature just wants some water when one of the gang slaps him, resulting in the Creature retaliating by slashing his face open. It's a shocking but funny image, especially after the creature is baffled and pained by the chlorine in the pool's water. Things go downhill from there, as St. John subverts the Creature/beautiful woman trope in gleefully horrifying ways.

"Horns" and "King Of The Hill" are silent stories featuring dinosaurs, and they are written with wit and verve. The fact that St. John clearly delights in drawing these creatures goes a long way to making the stories lively and fluid. The action is clear, the motivations make sense, and the sense of resigned patience on the part of the apex predators is all part of the comedy. The lush backgrounds provide the needed atmosphere to give the story some context without impeding the action.

St. John's former anthology series was called Monsters and Girls, and that speaks to his love of featuring femmes fatale in a number of different roles. In this collection, "Magic In The Moonshine" is about a witch who doubles as a burlesque dancer during prohibition times, and the aesthetic is a tribute to the Max Fleischer cartoons of the time. She winds up dodging demons and bible-thumpers by dropping in on a bootlegger who had a crush on her, and the resulting story is sweet and trippy. St. John is at his absolute best here in dipping between drawing her as a sexy woman and as a pile of bones, and the "magic drink" hallucination sequences are a particular pleasure.

"Dance Of The She Beast/Redneck And The Wolves" speaks to a different kind of femme fatale and a far less discerning audience. It takes the trope of the woman/witch turning into a wolf in the woods and subverts the hunter as Good Guy in this role, with a shockingly visceral death scene that ironically underscores his claims of being a hero. The subsequent story continues his shaky narrative, but there are dire consequences for him as a result. His story starring "Furiosa Frankenstein" combines the Bride of that particular monster with the ass-kicking heroine of the recent Mad Max update. This story mixes horror with action, as she has to fight the creatures in front of her as well as an imagined, twisted version of herself back at the lab where she was born. The visceral quality of his drawings is at his most detailed here, as the monsters drip with menace and gore.

Finally, "Whispers In The Woods" and "The Devil's Magic" reflect St. John's interest in having the mundane confront the extraordinary. The former story is about a couple of friends who go back and forth between thinking they're in horrible danger and trying to disbelieve in it, with increasingly rising stakes. Their reactions to what they see are hilarious, especially as the images become more and more bizarre, disturbing and monstrous--but not all is as it seems. The latter story is a funny, silent story, as a demonic figure shows up at a little creature's birthday party to perform the most mundane of tricks, yet those tricks are more impressive than him appearing and disappearing in puffs of smoke. St. John's line here is thin and expressive, emphasizing the almost dainty quality of the goat-creature magician's hands. This is a strong collection that fans of classic horror and more recent comedy-horror will appreciate.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #26: Brainworm 1-2

Anthologies have always been the lifeblood of CCS. In addition to work that's assigned to the students, there have often been cartoonists who have chosen to put together work with fellow students and alums. How the work is put together is often up to whichever cartoonist takes it upon themselves to edit the anthology, and in the case of the two recent volumes of Brainworm, that person is Kat Ghastly. She billed this anthology as "a catalog of obsessions for the obsessed" and themed both issues, giving them a nice sense of loose coherence. The table of contents in the first issue contains a sign-up sheet where most artists who said yes agreed at the expense of sleep or possibly quality, which speaks to the work ethic of the average CCS cartoonist.

The theme of the first issue is Endings. Tim Patton's stylish strip is about a couple of friends who visit an out-of-the-way coffee shop on its last day, and it's all about that sense of wistfulness that one feels in moments like that. The use of steam lines speaks to the ephemeral nature of the moment and then the memory. Hachem Reslan's silent strip is clever; it starts from heavily rendered as we see two hands: one holding a knife and other other an orange. As there is a surprise thing that is cut, the rendering and lighting gets lighter and less distinct, as though the cut hand is the one that's drawing the strip. Kristen Shull's cartoonish line is a delight in her story about songs that she can't get out of her head; it's a bit of fun that she braces with the final observation that banishing lingering thoughts is much more difficult. Sage Persing makes use of the dark in talking about their childhood OCD thoughts. Leise Hook's obsession with knowing how stories end was also cleverly drawn, with literalizations of the metaphors she was using. Bailey Johnson's drawing of a camera they took apart spoke to the way that working with its parts was soothing.

Unsurprisingly, CCS fellow Keren Katz's contribution was hilarious, odd and unsettling. It mixes drawings and photos (with a curly mustache drawn on Katz's face!) as the story follows a curator trying to figure out how to display the new heads. Each image is very typical of Katz, in that she's interested in exploring the way images in motion flatten themselves vs the ways in which still images can be arranged so as to create a strange synthesis. Ghastly's own strip is an amusingly cathartic story where she imagines people she hates falling into an open sewer grate, and then she thinks about what that fate may be. Her use of blobby figures reminiscent of Keith Haring drawings gives her story a strong visual charge.

The second issue isn't quite as interesting, in part because the topic ("The Undead") is a bit played out, and thus there was less variety on display. Katz once again takes an eccentric approach to an idea by taking three different documents (instructions for taking care of a cat, an origami instruction book and a book on making bubbles) and challenges people to come up with the first sentence of each book. It's all for reviving a monster. Katz is a walking idea machine, her brain and/or her body in constant motion as part of her relentless project to brighten the world with whimsical, bizarre and thought-provoking art.

There are some nice illustrations provided throughout by CCS instructor and horror master Steve Bissette, but they clashed with the generally lighthearted fare in the rest of the anthology. For example, Kurt Shaffert's "Bioethics and Zombie-care" is a funny take on how the rules of research (autonomy, beneficence, etc) would apply to dealing with zombies. Ghastly's own strip is about her own actual fear of zombies, or rather, that someone she loved would try to destroy her unexpectedly. Reslan and Persing's collaboration follows a sort of mannered, doomed romance, only one half of the couple is a zombie. Andres Catter's zombie gag is a funny one, using an image per page for maximum impact. Leise Hook's comic about a plant she revived and then might have killed again is a clever take on the theme, and its understated visual approach blends nicely with the text.

The theme of the first issue is Endings. Tim Patton's stylish strip is about a couple of friends who visit an out-of-the-way coffee shop on its last day, and it's all about that sense of wistfulness that one feels in moments like that. The use of steam lines speaks to the ephemeral nature of the moment and then the memory. Hachem Reslan's silent strip is clever; it starts from heavily rendered as we see two hands: one holding a knife and other other an orange. As there is a surprise thing that is cut, the rendering and lighting gets lighter and less distinct, as though the cut hand is the one that's drawing the strip. Kristen Shull's cartoonish line is a delight in her story about songs that she can't get out of her head; it's a bit of fun that she braces with the final observation that banishing lingering thoughts is much more difficult. Sage Persing makes use of the dark in talking about their childhood OCD thoughts. Leise Hook's obsession with knowing how stories end was also cleverly drawn, with literalizations of the metaphors she was using. Bailey Johnson's drawing of a camera they took apart spoke to the way that working with its parts was soothing.

Unsurprisingly, CCS fellow Keren Katz's contribution was hilarious, odd and unsettling. It mixes drawings and photos (with a curly mustache drawn on Katz's face!) as the story follows a curator trying to figure out how to display the new heads. Each image is very typical of Katz, in that she's interested in exploring the way images in motion flatten themselves vs the ways in which still images can be arranged so as to create a strange synthesis. Ghastly's own strip is an amusingly cathartic story where she imagines people she hates falling into an open sewer grate, and then she thinks about what that fate may be. Her use of blobby figures reminiscent of Keith Haring drawings gives her story a strong visual charge.

The second issue isn't quite as interesting, in part because the topic ("The Undead") is a bit played out, and thus there was less variety on display. Katz once again takes an eccentric approach to an idea by taking three different documents (instructions for taking care of a cat, an origami instruction book and a book on making bubbles) and challenges people to come up with the first sentence of each book. It's all for reviving a monster. Katz is a walking idea machine, her brain and/or her body in constant motion as part of her relentless project to brighten the world with whimsical, bizarre and thought-provoking art.

There are some nice illustrations provided throughout by CCS instructor and horror master Steve Bissette, but they clashed with the generally lighthearted fare in the rest of the anthology. For example, Kurt Shaffert's "Bioethics and Zombie-care" is a funny take on how the rules of research (autonomy, beneficence, etc) would apply to dealing with zombies. Ghastly's own strip is about her own actual fear of zombies, or rather, that someone she loved would try to destroy her unexpectedly. Reslan and Persing's collaboration follows a sort of mannered, doomed romance, only one half of the couple is a zombie. Andres Catter's zombie gag is a funny one, using an image per page for maximum impact. Leise Hook's comic about a plant she revived and then might have killed again is a clever take on the theme, and its understated visual approach blends nicely with the text.

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #25: Kevin Uehlein, Pat Barrett, DW

Pigeon Man #2 and #4, by Pat O'Brien, Zack Poitras (writers) and Pat Barrett. Barrett drew this visceral, disgusting and over-the-top satire of politics, capitalism and the culture that surrounds them. If anyone was up to the job of drawing the adventures of a superhero who combined the aspects of pigeon and man in the most revolting ways possible, it's Barrett. His humor comics have always had that quality of being game for anything, and that's certainly true here. I unfortunately was only able to read the 2nd and 4th issues of the comic, so I can't comment too much on the story. The basics are that the mayor of New York City is kidnapping orphans and grinding them into sausage, and only Pigeon Man and his friend the Commissioner of the police can stop him. Hilariously, the mayor uses the New York Rangers hockey team as his stooges. Pigeon Man himself is a disgusting character, frequently lapsing into heavy drug and alcohol-fueled binges as he does things like go down on a bat. Tucker Carlson gets seduced, various rescue missions are attempted, horrific sausage is consumed, and Pigeon Man's prison-bound daughter wreaks havoc. The comic is a bit of a grind sometimes because it never lets up, making it something of a breathless experience. Still, Barrett's saturated use of color and ability to mix a cartoonish style with realism make the gags work.

Kevin Uehlein's solo project was the immense minicomic Quit Rasslin' Me!, an epic deconstruction and parody of the WWE and pro wrestling in general. Featuring his anthropomorphic characters Disgusting Duck and Dumbass Dog, those two go from "back alley wrestling" to the WWE when the corporation was beset by steroid scandals, sexual harassment claims and being increasingly out of touch with the fans. As ludicrous as the action in this comic is (and it goes way over the top), virtually everything in it is based on something that actually happened. The Duck is chosen to be the new, hot babyface and even gets tabbed as the new champ, since he's cheaper than maintaining the older, Hulk Hogan-like mainstay. The Dog is chosen to be a heel who can reliably take chair shots to the head and get sent through tables, no matter the damage to his body. There's turn after turn here, as an arrogant Duck gets taken down by an Undertaker-like version of the Dog, who then decides to become a born-again Christian. This is a funny, silly comic with appealing, rubbery art that is entertaining in its own right in addition to being a dead-on satire of the WWE's greed and questionable ethics.

KJC 4 is Uehlein's sketchbook collaboration zine, done with the artist DW as well as James Stanton and Dakota McFadzean. Uehlein's bigfoot wackiness and DW's intense mark-making and pattern designs make for a compelling mix, and they do all sorts of things to create a variety of visual experiences. For example, there are pages that are transparencies, laid over a paper page. The drawings on the transparency interact with the drawings on the page in interesting ways, deliberately adding new details and contexts for them. In the middle of the comic, there's a stapled-in micro mini that features Uehlein-designed characters talking, only their word balloons contain DW's patterned drawings that feature strange animals and fossils in the middle. There are also occasional comic strips with interjections from DW that contribute to the dense glee of this project.

Compulse 10 and an untitled mini from DW round out the comics here. Compulse is Uehlein's micro-mini sketchbook project, and this edition focuses on a female character with various hairstyles in profile. Uehlein really has a knack for drawing angry cartoon degenerates. DW's zine has more of his current interest: circular designs that resemble mandalas, containing a bird, a lizard or some other creature in its center. He alternates between black & white and color, with the former looking bolder and the latter more visually appealing. They almost look like cave drawings or some kind of ancient image that's been long buried.

Monday, December 24, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #24: A Whole Lifetime Of Firsts

A Whole Lifetime Of Firsts. This is the second collaboration between CCS cartoonists and the White River Junction VA, featuring veteran's stories focusing in on women. The first CCS/VA collaboration was good, but this one is excellent. There's a level of depth and execution in transcribing the stories of women in the military in a variety of ways that's striking. On top of that, telling stories that haven't necessarily been part of the public discourse up til recently is also something that adds to their impact.

"Mitzi's Story" is written by co-editor J.D. Lunt (CCS president James Sturm is the other editor). She is a former NCO who wound up in places like Kosovo and Iraq. For her, even though she's a closeted lesbian, military service was her life. That was also despite a sexual assault and soldiers of lower rank frequently ignoring her orders. When she was honorably discharged because of an injury, she was ill-equipped to face civilian life despite being married. She got hooked on drugs, arrested and tried to kill herself before really deciding to embrace rehab. After a lifetime of being told she wasn't good or smart enough and enduring enough PTSD for a dozen people, her ability to endure and thrive is simply remarkable. Garcia uses a standard nine-panel grid with a visual approach that's a little ragged, yet appropriate for the subject.

"I Got Your Six" is from Daryl Seitchik & Dan Nott, and it's about an Army nurse who was in Viet Nam. There's a lot of story to tell here, and Seitchik & Nott use a twelve-panel grid to pack it all in. Despite that, they tell the story with a great deal of clarity, making frequent use of switching black & white negative space. Every panel is well-balanced in this regard, making the linework easy to grasp and contextualize. This story focuses more on her experiences in the war as a nurse and less on what happened afterwards, though she does note how much hostility she faced as a veteran of Viet Nam when she returned. What I found most fascinating is her intuitive understanding of how important psychological care was for soldiers in addressing PTSD at a time when it was not understood or used.

"Isolated Duty" is a story with the opposite scenario: a woman in the Navy in the 70s got injured and met the love of her life who was also a woman in the military. Drawn by Rachel Ford and written by Sarah Yahm and Kurt Shaffert, this is a nicely-constructed comic that at times is perhaps a bit too spare with regard to facial expressions. The theme of being taken care of and now taking care of her partner resonates, especially with the way they keep their romance alive despite her partner's increasingly diminished mental capacity. Finally, "Kathi: A Life Well Traveled" is about an Air Force nurse who was in Europe and later Viet Nam, and it's by Catherine Garbarino and Kelly L. Swann. The artists make extensive use of grayscale shading to add to the sense of this being akin to an old book of photos, filled with memories. Kathi is a relentlessly upbeat presence and was regarded as such in Viet Nam, even earning a Bronze Star for the way she enhanced morale. This is not to say that there weren't painful moments, like a truck accident that she still couldn't discuss, and a young boy in a leper colony that she wanted to adopt but couldn't, but she still mostly stayed positive. All of this was told from her perspective of being treated for cancer at eighty years old, staying positive to the end. The way each story had a different focus and featured several different armed services spoke to the variety of experiences, as well as the need for each of these women to tell their story. These are stories that needed to be told, and the artists found different ways to get there.

Sunday, December 23, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #23: Luke Howard and Penina Gal

Match, by Luke Howard. Every year, CCS sends out a comics pamphlet detailing the benefits of the school in a general way and specifically asking for donations. Howard, an administrator at the school and also a graduate, wrote this year's pamphlet for 2018. Unsurprisingly, it's funny and quirky, with its main concept being that giant hands from the sky often come to help us when needed. These "helping hands" later help cartoonists match up with "top-notch teachers" at CCS in addition to helping humanity at larger, spurring any number of theories as to what they actually are. Howard, never afraid to go meta, actually has a character posit the idea that the giant hands are a metaphor, which gets the character roundly ridiculed by his friends. At the very end, there's a pull-back that reveals that a grandpa was reading the story to his grandkids, who found it a "little...one-note". At the same time, Howard stays on mission as the kids ask "why didn't the cartoon school just come out and ask for donations directly?"--and then turn and look at the reader.

This is a bit of applied cartooning, to use the term championed by CCS founder James Sturm, but it's entirely in Howard's style. Howard is someone who can work in any style, but he's really come into his own over the last few years. He has his own take on the stripped-down figure style based on simple geometric shapes. His storytelling mixes utter sincerity with distancing irony at the same time, creating an absurd atmosphere that the reader must navigate on several levels. In this case, Howard directly addresses the reader in an attempt to ask for donations to the school, but the level of distancing in the comic also addresses the fact that doing so is humiliating. Throw in his usual, slightly pained sense of humor, and you have a pretty remarkable comic.

Drift, by Penina Gal. This continues Gal's more recent trend of doing more abstract, poetic comics. This one is built around swirls of color on the left side of the page and a four-panel grid on the right that's mostly just text. The overall effect is a rhythmic one, as patterns and colors rise and fall around the text. Gal writes about ADHD in this comic and makes the sage comic that the disorder is only pathological in a capitalistic society that demands focus on a particular task and actively discourages daydreaming. There's a sense of resentment that she has to take drugs and go to therapy for something that doesn't actively distress her; she's being forced to alter her brain in a way she doesn't want. It's also an example of a comic that I've seen a lot of lately, which is how to cope with living in Trump's America as part of a marginalized group, especially as a highly empathetic person The mix of anger and activism with calls for self-care is very much part of this, but (on brand) Gal drifts back to thinking about the hows and whys of her brain's function. In particular, she notes that her therapist posited the idea that her brain "processes tasks through emotion rather than deliberation." It's an interesting idea, focusing in on the executive functioning portion of the brain. Someone who processes information emotionally is susceptible to emotional burnout and overload, which is why the self-care aspects of the comic were so important. For a comic built on personal feelings and experiences, Gal outlines the mechanics of this empathy and its relationship with focus with a great deal of precision.

This is a bit of applied cartooning, to use the term championed by CCS founder James Sturm, but it's entirely in Howard's style. Howard is someone who can work in any style, but he's really come into his own over the last few years. He has his own take on the stripped-down figure style based on simple geometric shapes. His storytelling mixes utter sincerity with distancing irony at the same time, creating an absurd atmosphere that the reader must navigate on several levels. In this case, Howard directly addresses the reader in an attempt to ask for donations to the school, but the level of distancing in the comic also addresses the fact that doing so is humiliating. Throw in his usual, slightly pained sense of humor, and you have a pretty remarkable comic.

Drift, by Penina Gal. This continues Gal's more recent trend of doing more abstract, poetic comics. This one is built around swirls of color on the left side of the page and a four-panel grid on the right that's mostly just text. The overall effect is a rhythmic one, as patterns and colors rise and fall around the text. Gal writes about ADHD in this comic and makes the sage comic that the disorder is only pathological in a capitalistic society that demands focus on a particular task and actively discourages daydreaming. There's a sense of resentment that she has to take drugs and go to therapy for something that doesn't actively distress her; she's being forced to alter her brain in a way she doesn't want. It's also an example of a comic that I've seen a lot of lately, which is how to cope with living in Trump's America as part of a marginalized group, especially as a highly empathetic person The mix of anger and activism with calls for self-care is very much part of this, but (on brand) Gal drifts back to thinking about the hows and whys of her brain's function. In particular, she notes that her therapist posited the idea that her brain "processes tasks through emotion rather than deliberation." It's an interesting idea, focusing in on the executive functioning portion of the brain. Someone who processes information emotionally is susceptible to emotional burnout and overload, which is why the self-care aspects of the comic were so important. For a comic built on personal feelings and experiences, Gal outlines the mechanics of this empathy and its relationship with focus with a great deal of precision.

Saturday, December 22, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #22: Carl Antonowicz

Buer's Kiss Volume I, by Carl Antonowicz. I only got to see the first few pages of this in minicomics form last year, but there's no question that this is Antonowicz's best, most confident work to date. He was so ambitious that he also created a stage version of this story, which played in a few different locations. Antonowicz is most interested in stories set in a fictional version of the European middle ages, mixing science, religion, magic and superstition. This comic was inspired by the story of a particular leper's colony in the 14th century and it involves the ways in which beliefs become so reified that they supersede reason and observation. That's especially true when the church and state are essentially the same entity.

Stories like this are best old at the individual level, which allows the reader to focus in on the particular affairs of someone while trying to figure out what's going on. Antonowicz starts the story with what seems to be a funeral until we learn that the woman being "buried" is not actually dead, but somehow Unclean. The penalty is to be exiled from the village, with the choice of becoming a beggar or joining a colony of diseased heretics. The woman, Felecia, is a independent cynic with a dark sense of humor, which makes her an ideal protagonist. Far from the Candide-like innocent thrown on the mercies of a cruel world, she's smart and self-possessed despite having no formal education. This is a protagonist with the kind of agency necessary to survive a world like this but also the common sense needed when it came time to compromise.

This is a story about the arbitrary nature of authority. When authority ceases to have a rational reason for being, it simply becomes a matter of maintaining a status quo through the use of naked force. That's especially true when authority trumps human empathy. Antonowicz plays this out in a number of scenarios. First, when Felecia's husband refuses to touch her, she realizes that he chose to let all of their years together be wiped out by the beliefs of the village. Second comes when a soldier on a mission to find the colony of the diseased realizes that his commanding officer is not only incompetent, he's in love with the sound of his own commands. Third is when Felecia meets the colony's doctor and is relieved to hear that the doctor doesn't believe in the proclamations of the diseased leader. Fourth is when Felecia meets a diseased man (who believes in an approximation of Islam) who warns her about everyone's belief system. This volume builds up these conflicts, while I imagine the second volume will bring them to fruition.

The story works because Antonowicz pays close attention to detail. He doesn't skimp on depicting the leprosy-like disease labeled as the titular "kiss", with boils, sores, scabs, missing body parts, etc. He makes great use of negative space throughout the comic, which is crucial since he uses a small twelve-panel grid as his default. There are times parts of the grid are collapsed to become a single, horizontal panel, but Antonowicz keeps things moving using this format. This is a visually striking comic first and foremost, allowing the character and plot to reveal themselves slowly while the reader takes in visual details. I'm eager to see the payoffs for a variety of characters and stories in the next volume.

Stories like this are best old at the individual level, which allows the reader to focus in on the particular affairs of someone while trying to figure out what's going on. Antonowicz starts the story with what seems to be a funeral until we learn that the woman being "buried" is not actually dead, but somehow Unclean. The penalty is to be exiled from the village, with the choice of becoming a beggar or joining a colony of diseased heretics. The woman, Felecia, is a independent cynic with a dark sense of humor, which makes her an ideal protagonist. Far from the Candide-like innocent thrown on the mercies of a cruel world, she's smart and self-possessed despite having no formal education. This is a protagonist with the kind of agency necessary to survive a world like this but also the common sense needed when it came time to compromise.

This is a story about the arbitrary nature of authority. When authority ceases to have a rational reason for being, it simply becomes a matter of maintaining a status quo through the use of naked force. That's especially true when authority trumps human empathy. Antonowicz plays this out in a number of scenarios. First, when Felecia's husband refuses to touch her, she realizes that he chose to let all of their years together be wiped out by the beliefs of the village. Second comes when a soldier on a mission to find the colony of the diseased realizes that his commanding officer is not only incompetent, he's in love with the sound of his own commands. Third is when Felecia meets the colony's doctor and is relieved to hear that the doctor doesn't believe in the proclamations of the diseased leader. Fourth is when Felecia meets a diseased man (who believes in an approximation of Islam) who warns her about everyone's belief system. This volume builds up these conflicts, while I imagine the second volume will bring them to fruition.

The story works because Antonowicz pays close attention to detail. He doesn't skimp on depicting the leprosy-like disease labeled as the titular "kiss", with boils, sores, scabs, missing body parts, etc. He makes great use of negative space throughout the comic, which is crucial since he uses a small twelve-panel grid as his default. There are times parts of the grid are collapsed to become a single, horizontal panel, but Antonowicz keeps things moving using this format. This is a visually striking comic first and foremost, allowing the character and plot to reveal themselves slowly while the reader takes in visual details. I'm eager to see the payoffs for a variety of characters and stories in the next volume.

Friday, December 21, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #21: Jen Vaughn and Moss Bastille

Goosebumps: Download and Die!, by Jen Vaughn and Michelle Wong. Vaughn is one of a handful of CCS grads working with licensed properties in addition to working on her many other projects. This indefatigable artist always seems to be writing or drawing a comic in addition to running podcasts and other multimedia project. The work she shared with me is a three-issue miniseries collection of an original story she wrote using R.L. Stine's horror-for-kids Goosebumps property. While the villains of the story are all Goosebumps veterans, everything else in this story was her concept. I did miss seeing her do the art for this story, but Wong's more mainstream-friendly work obviously made a lot more sense in this case. Many of the most successful comics for kids are now explicitly aimed at girls, featuring girls as characters and produced by women. It's a fascinating paradigm shift compared to twenty, ten or even five years ago. The fact that it took this long reveals more about publishers and editors who made poor assumptions than it does the women who are producing these successful series.

Vaughn was clearly made for projects like this, as she quickly sells the reader on the friendship of two girls (Mitra and Kyra, both people of color, incidentally) and also sells the reader on Mitra being threatened by a new girl, nicknamed "Flips". It takes exactly five pages to establish the personalities of the three leads, the interpersonal conflict that Mitra feels, and the catalyst for the plot: Mitra's phone being broken. When she mysteriously gets sent a new phone loaded with cutting-edge apps and cool filters, she sets the plot into motion. What makes the story work is that even though the reader knows that the phone is evil, Vaughn still keeps enough details mysterious and keeps the horror elements rooted in the central conflict of the story. Vaughn throws a lot of weird supernatural details at the reader in an effort to keep them off-balance, and it works.

There are evil puppets, menacing skeletons, lizard people trying to infiltrate humanity in order to create more lizard people, and a weird melting kid. The phone makes people sick, allows Mitra to hear the thoughts of others and it makes her paranoid by talking to her. The pacing of the story is a bit wobbly at times, especially with regard to action scenes and the story's climax. While the Goosebumps series is aimed at kids and thus rarely doubles down on its horror elements in a graphic manner, the climax lacks tension amidst its goofiness. The tension that Vaughn builds doesn't quite pay off, and some of that is on Wong. She's great at character interaction, but her panel-to-panel transitions during action scenes aren't especially smooth. That said, Vaughn and Wong stick the landing with the end, which picks up a particular loose end and takes it in a disturbing direction. All told, Vaughn spins a tale that mostly works because of the believability of its cast as well as the existential threat of an all-seeing cell phone.

Speaking of horror, Moss Bastille's comics offer up stylish world building with a look somewhere between Richard Sala and John "JB" Brodowski. The Burning Room, an oversized comic that is stated to be the first chapter of a longer work titled The Obscure Road. It makes a perfectly fine stand-alone comic, dripping with atmosphere and mystery. Bastille sets the mood with a young man approaching a wrecked house but immediately lets the reader know that things are at least slightly weird because of his bizarre, dog-like pet. The man, whose name we later learn is Perigale, narrates the history of the house and one room in particular. Following a specific set of instructions, the heartbroken can enter the room, pin up a photo of the one who broke their heart, sleep in the room, and then forget their beloved forever after.

Having established the rules, Perigale enters the room and proceeds to break all of them. He contacts the trapped spirit in the room and proceeds to make a bargain with it. This comic is very much about rules, trust and protocol, as the spirit's story is a sad one. This comic is all about negative space and gradations of black, white and gray. One can see the intense amount of labor on each page in order to create these effects, but Bastille is careful to give his figures a clear, almost casual and cartoonish look like Sala. The spirit creature is genuinely unsettling, thanks to that mix of contrasts; its form is elongated and unnatural, adding to its unnerving quality. Bastille hit on something engaging with this concept.

Glass Eye #1 is a mini whose visual approach is completely different. It's a panel per page, relying heavily on line and hatching. It's somewhere between horror and poetry, with the big block letters on each page narrating a story about being so haunted by one's past that it causes one to try to forget it and escape it. The inevitable end is to be both victim and victimizer--never forgetting and never escaping. It's nowhere near as visually arresting as the other comic, but its intent is a short burst of bold, disturbing images and ideas as opposed to a more coherent narrative.

Vaughn was clearly made for projects like this, as she quickly sells the reader on the friendship of two girls (Mitra and Kyra, both people of color, incidentally) and also sells the reader on Mitra being threatened by a new girl, nicknamed "Flips". It takes exactly five pages to establish the personalities of the three leads, the interpersonal conflict that Mitra feels, and the catalyst for the plot: Mitra's phone being broken. When she mysteriously gets sent a new phone loaded with cutting-edge apps and cool filters, she sets the plot into motion. What makes the story work is that even though the reader knows that the phone is evil, Vaughn still keeps enough details mysterious and keeps the horror elements rooted in the central conflict of the story. Vaughn throws a lot of weird supernatural details at the reader in an effort to keep them off-balance, and it works.

There are evil puppets, menacing skeletons, lizard people trying to infiltrate humanity in order to create more lizard people, and a weird melting kid. The phone makes people sick, allows Mitra to hear the thoughts of others and it makes her paranoid by talking to her. The pacing of the story is a bit wobbly at times, especially with regard to action scenes and the story's climax. While the Goosebumps series is aimed at kids and thus rarely doubles down on its horror elements in a graphic manner, the climax lacks tension amidst its goofiness. The tension that Vaughn builds doesn't quite pay off, and some of that is on Wong. She's great at character interaction, but her panel-to-panel transitions during action scenes aren't especially smooth. That said, Vaughn and Wong stick the landing with the end, which picks up a particular loose end and takes it in a disturbing direction. All told, Vaughn spins a tale that mostly works because of the believability of its cast as well as the existential threat of an all-seeing cell phone.

Speaking of horror, Moss Bastille's comics offer up stylish world building with a look somewhere between Richard Sala and John "JB" Brodowski. The Burning Room, an oversized comic that is stated to be the first chapter of a longer work titled The Obscure Road. It makes a perfectly fine stand-alone comic, dripping with atmosphere and mystery. Bastille sets the mood with a young man approaching a wrecked house but immediately lets the reader know that things are at least slightly weird because of his bizarre, dog-like pet. The man, whose name we later learn is Perigale, narrates the history of the house and one room in particular. Following a specific set of instructions, the heartbroken can enter the room, pin up a photo of the one who broke their heart, sleep in the room, and then forget their beloved forever after.

Having established the rules, Perigale enters the room and proceeds to break all of them. He contacts the trapped spirit in the room and proceeds to make a bargain with it. This comic is very much about rules, trust and protocol, as the spirit's story is a sad one. This comic is all about negative space and gradations of black, white and gray. One can see the intense amount of labor on each page in order to create these effects, but Bastille is careful to give his figures a clear, almost casual and cartoonish look like Sala. The spirit creature is genuinely unsettling, thanks to that mix of contrasts; its form is elongated and unnatural, adding to its unnerving quality. Bastille hit on something engaging with this concept.

Glass Eye #1 is a mini whose visual approach is completely different. It's a panel per page, relying heavily on line and hatching. It's somewhere between horror and poetry, with the big block letters on each page narrating a story about being so haunted by one's past that it causes one to try to forget it and escape it. The inevitable end is to be both victim and victimizer--never forgetting and never escaping. It's nowhere near as visually arresting as the other comic, but its intent is a short burst of bold, disturbing images and ideas as opposed to a more coherent narrative.

Thursday, December 20, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #20: Anna Sellheim and Matthew New

Art Model, by Mathew New. This webcomic is a fascinating mix of media in an autobio context. Using the cartoonish style he's best known for, New discusses his career as a nude art model, telling a story both about the process of the experience as well as the way he relates it to his feelings about his own body. New really spills some ink here, talking about a lifetime of negative body image that was only compounded when the only thing he liked (his thinness) started to manifest as an eating disorder. The story is interspersed with different friends of his and their drawings/paintings of him, done in a myriad of styles. New talks about how becoming an art model both required and helped him gain self-confidence. The essential point he makes is that the things one might hate most about themselves are the things that are most interesting to draw, which is a fascinating way of turning self-hatred into not just utility, but the potential for art.

Mindfulness and meditation are often discussed as important therapeutic tools, and New discusses how the reality of being a model means long periods of time where you have to find ways to do nothing but sit or stand there. That means being alone with one's own thoughts and learning how to be still with one's own naked body in that space. New also discusses some of the smaller steps that allowed him to take this big step to become comfortable in his own skin, the thought he puts into particular poses and how it might help artists, and other related information. Being an artist who's worked with live models also instructed his approach and allows him to understand both sides of the equation. That's why the many different artists whose takes on him he reproduced here are so important, because it's active proof of how he was able to inspire each of them to draw something interesting. It's not just the form an artist is drawing, but also a way of approaching a different visual problem and figuring out ways to solve it. It's an active way for artists to develop new ways of thinking, even if their actual work is abstract, cartoonish or otherwise not directly related to figure drawing. New's own hard-won sense of self-validation allowed him to gain further validation in the way his job inspires others.

Moments and various short stories by Anna Sellheim. Sellheim quickly became one of my favorite CCS cartoonists on the strength of the rawness of her work. Her autobio material in particular is no-holds-barred with regard to her own feelings and experiences, and I love the jagged, jarring quality of her line and her self-caricature. Sellheim shared a number of her stories from anthologies. First off are stories from a few volumes of the Square City Comics anthology, which she helped start. "The Best Laid Plans", in volume 1, is a work of slice-of-life fiction. It's a romance story, about a bartender who refuses to date her customers falling for a woman who's part of a group of friends who are regulars at the bar. What makes the story work so well is the way Sellheim makes the reader feel the desperation of Ivy the bartender in keeping her life on track as a recovering addict and how hard she clings to this rigidity. In the end, when her life plan goes off track, she realizes that losing control of this rigidity can be a good thing. Sellheim keeps the grid and the art simple, playing up her use of gesture and characters relating in space. This does everything to sell the emotion on the page.

"Expanding My Horizons" in volume 2 is an autobio story that focuses on her newfound love of superhero comics. There's an almost frantic energy in virtually everything Sellheim does or thinks about, and this history of her relationship with comics is no different. Starting with manga as a ten year old, segueing into art comics in high school and finally trying to find something more lighthearted after the death of her father, she started to become interested in some superhero work. The comic explains what she liked and didn't like and why. Two things stand out here: first, the grotesque quality of her art (her self-caricature here is intentionally self-deprecating) and the sheer importance of her pursuit. Comics matter to her as a way of experiencing the world and focusing her attention and emotions, and it was obvious that finding the right titles at the right time was the most profound of pursuits.

Moments is a profound departure for Sellheim. This mini features her working in color, using a four-color grid to not just depict quiet, quotidian moments in the lives of ordinary people, but to show small but profound changes in expression. In the examples above, we see a person end a phone call, pause and put their head up to their temple. Sellheim here goes after the small moments and the beats between moments, as the pose here went from contemplative to despondent. The scene with the woman on the subway is even subtler, as she's so absorbed in her book that she barely notices the world going by around her. Sellheim here uses color to reinforce line and push the reader's attention to the figure. Color framed that, considering that most of her figures themselves are not colored, drawing the reader to the line art. For an artist who usually depends so heavily on dialogue, it was an interesting and useful exercise.

The same is true for her entry in Square City Comics volume 4, "Rame". That's a word that means "chaotic and joyful", and it's entirely silent. It's about a woman attending a house party/concert. She's timid at first as she negotiates the chaos of so many people and their intense energy, including the unwelcome event of someone flirting with her. There's a panic attack as a result, which leads to her fleeing to another room, but the sheer, raw energy of the band not only helps with that, it encourages her to get right up front and mosh. The character design reminds me a little of Liz Suburbia here; there were points where it seemed like Sellheim struggled a bit in coming up with a large number of different character types, but her tight focus on the main character helped with that problem.

Finally, there are two autobio comics in Sellheim's more typical style, though the second one uses regular figures instead of her stripped-down image. One was in a comics newspaper called Magic Bullet, and it's a funny strip that makes great use of its full-page layout by using a great deal of negative space. It's about her trying to meditate for the first time, with her caricature mostly being white space juxtaposed against the gray scale shading containing every negative thought imaginable about herself. The punchline is both funny and bracing, as the last thing she's achieved is a "new sense of calm" after dealing with those relentless feelings. The second is a strip about how hard depression hit her, to the point where she didn't feel like she was living her life until the age of 25. It gets at the heart of depression: the mental pain that comes with it, and the desire for the pain to just go away. The jagged quality of her line once again serves to give the comic a certain uncomfortable quality, which is a hallmark of her comics. More than any other cartoonist I can think of, Sellheim is figuring out what she wants to do with comics in parallel with what she wants to be as a person. The struggles she feels seem to be working in concert with each other in terms of both life and art, as do the solutions. That she chooses to share both with her readers is our privilege.

Wednesday, December 19, 2018

Thirty One Days Of CCS #19: Dan Nott and Curtis Thomson

Today's entry features work from an artist who not only was in his first year at CCS, he had almost no experience as a cartoonist. It also features the exquisitely detailed thesis project of a graduating senior.

Curtis D. Thomson is the father of Quinn Thomson, a fellow first-year student at CCS last year. Cartooning is a path that Quinn wanted to take, and Curtis accompanied him to classes at the Joe Kubert School. Curtis was a watch repairman by trade, but it became increasingly obvious that he not only had the talent to be a cartoonist, he also had the desire. So both Thomsons are at CCS, and their styles are dramatically different. Looking over sample work and his Industry Day Comics mini, it's obvious that in terms of drawing and cartooning, he can work in any style. He's that rare natural who just has an uncanny level of skill.

His version of the Aesop's Fables project centered around "The Birds, The Beasts and the Bat", drawn in an ink-stained, Steve Bissette style of art suitable for horror. Everything from his lettering to his scratchy and often spare line was used effectively to create a dark atmosphere. "Metamorsel" appears to be a comic based on Wally Wood's classic "22 Panels That Always Work". There are multiple instances of a variety of different shots, including silhouette, foreground-background switches, light and dark contrast and more. The story is about a father misplacing a cookbook that he thought his wife no longer wanted, and the trouble that causes. "Meditation Comic" uses three different visual approaches, stacked in 2 vertical panels apiece: a sketchy style that utilizes white space, a more labored style that emphasizes light/dark contrasts; and two panels that heavily rely on spotting blacks. The result is something along the lines of a poetry comic, though a bit more scattered because it's clearly stream-of-consciousness. That said, Thomson was able to pull the strip together thanks to its visual elements. Thomson may well be better suited to draw other people's stories, but I'm curious to see what he comes up with in his second year.

Dan Nott is a highly ambitious cartoonist specializing in journalism. He's already signed a book deal with First Second to do a book called Hidden Systems, which is about the mostly unseen and little-discussed infrastructure that allows the world to function: water, power, internet, etc. His thesis project is titled Lines of Light, and while it is certainly thoroughly-researched, its chief virtues are its clarity and simplicity. Nott provided me with the entire thesis package, including a number of related minis and sketchbook material. The book seeks to answer a single question: what is the internet, exactly? Nott answers the question with a great deal of detail but streamlines and simplifies the answers in a way that's easy to comprehend. Furthermore, he contextualizes the history and structure of the internet in a way that reveals how it's not really the great equalizer across the world, but instead is controlled by and serves the interests of those nations and corporate entities that hold power.

Nott begins talking about the issue by discussing the various metaphors for the internet: cloud, highway, tubes, etc. What all of them have in common is the idea that the internet is completely decentralized, while the truth is quite the opposite. He connects the internet to the telegraph, invented over 150 years ago, because the reality is that both of them rely on cables buried under the ground or laid at the bottom of the ocean. The map he shows of how similar the US interstate system is to internet cable lines is fascinating and shows how those areas are privileged. Nott notes that 97% of internet activity comes through these buried lines to carefully concealed exchange points--buildings with huge computers that connect data networks. The vast majority of these points are in the US and Europe--putting the lie to decentralization.

From cable to exchange points to data centers, these internet nexus points are not widely discussed or understood by the general public, and this is intentional. Nott lays out his argument neatly and cogently, as he draws back the curtain on anonymous-seeming buildings that are crucial parts of the internet. Nott slips between a 12-panel and a 9-panel grid, with the panels often slipping away at the bottoms of pages when the information coalesces into a single image. There are also times when he wanted to push just how large a facility was, so the image would expand over two pages, while he would keep the captions within the panels of the grid. His line is simple and clear, as he used a lightly cartoonish approach to make each image approachable for the reader. That also keeps each image slightly loose, allowing the reader to make quick panel-to-panel and page-to-page transitions without being thrown off. While there is an element of advocacy in this work, Nott keeps it dialed back, preferring to let the data do the talking and allowing the reader to make their own judgments.