Li Kunwu's A Chinese Life (Self-Made Hero) was originally printed in three separate volumes in France. Despite being an autobiographical account of his life of growing up in communist China, it is very much a European book. That's thanks in part to writer Philippe Otie, who wrote the script based on Li's original notes, but the actual formatting and formal qualities of the drawing are very European. Indeed, Li's skill with a brush rivals that of a master like Blutch, and there are any number of pages I stared at in awe. In some respects, the book is a weird cousin to Yoshiro Tatsumi's autobio book A Drifting Life. Both books take a long look at their childhoods, families and careers. Both are circumspect with regard to the romantic failures in their lives and in many respects don't care to spill much ink on their real secrets and emotions. What's different is that Li's book at a certain point went from being about a particular person's experience growing up in China to acting as a stand-in for the Chinese citizen in general, a burden that was most certainly felt in the third volume/chapter in particular. Both Tatsumi and Li are men consumed with their art, but they moved in entirely different worlds. Li's book in many ways is a more impressive achievement, both visually and narratively. All of that said, reading the book was an uncomfortable experience because I couldn't help shake the notion that the book is a work of propaganda.

I'll return to that thought when I examine the third volume of the book. The first volume, detailing his days as a child born right after Mao Zedong had taken power. Right from the start, when his father tried to get him to say their leader's name when he was just six months old, the volume relates the kind of craziness that can ensue under a cult of personality. Glorifying the Communist Party and the Revolution and allegiance to the infallibility of Mao were taken for granted as children. Of course, Li notes the ways in which that kind of allegiance crippled the country. First there was the Great Leap Forward, an attempt at aggressively industrializing China that helped to generate famine. The children were expected to help by killing pests, and to prove that they did, they had to bring a rat's tail to school. Poor Li had no success, something that led to a bit of ridicule.

Dogma got in the way of other pursuits like romance; there was one girl who was attracted to him whom he managed to put off by combining a romantic love letter with revolutionary lingo. It was hilarious, if harmless. Much more deadly was the Cultural Revolution of 1967, an event that lasted a decade. Li gave a first-hand account of this insane social psychology experiment, because he was one of its perpetrators. With slogans like "Revolution is not a dinner party", young children started shaming, bullying, lecturing and eventually reporting adults for being insufficiently devoted to the cause of revolution, for being bourgeois, and for being reactionary. It was sort of a reverse case of McCarthyism, only wholly adopted by children to use against their parents and their friends' parents. These young adults, who referred to themselves as the "Red Guard", got people killed, sent to re-education camps, and separated from their families for over a decade. The first book ends with Li in the army, his father in a camp and his sister working on a re-education farm. The climactic event of the book is the death of Mao, an event more catastrophic than any other for Li. More than that, it signals the end of a certain kind of idealism and naivete, both for Li and the nation itself.

Of course, it took time to get there. The second book opens with the "Gang of Four" being arrested for fomenting the worst aspects of the Cultural Revolution. These "excesses", including public "struggle sessions" and intense "self-criticism" that were essentially methods of public humiliation at best and torture at worst, tore China apart. Having a scapegoat allowed those who were still loyal to the Party (like Li and his father) to continue to hold on to their beliefs without examining them too closely. This volume drags much more than the other two, as it's mostly devoted to Li's attempts to join the Communist party while a member of the army. When he's rejected, he volunteers for farm duty. There are various failed romantic encounters, threats from other men and tedious accounts of life on the farm, until his skill with a brush is recruited for new propaganda posters.

Life as a propaganda artist for new leader Deng Xiaoping transformed Li's life, and I daresay it brought him into the bourgeoisie. Deng's "theory" preached pragmatism and development above all else. Li's father was released from a work camp and very quickly moved on from that period to embrace Deng. Hitting on the notion that becoming open to new ideas and techniques somehow didn't contradict the revolutionary mindset, noting "Thought liberation is also a form of revolution." The first tourists to China are introduced in this chapter, drawn in a comical and grotesque style. Li depicts this chapter as one where many Chinese, including his revolutionary father, started to come to terms with their pasts. The chapter ends with his father going back to his old village and performing old rites to honor his parents, who were "black bastard" land owners. The first two volumes reveal how Li was personally affected by the forces of history, though the second volume lost the intense focus of the first.

The third volume, "The Time Of The Money", is Li's modern-day take on China's assimilation of capitalism (which they refer to simply as a "market" economy). Li became an editorial cartoonist for a daily newspaper, and his job was to go out in public and draw what he saw--draw the "real" China, as was happening on the streets. Li portrays himself as a crusader against the kind of corruption brought about by greedy men trying to rip others off, but doesn't see this as a reason to be down on capitalism. Indeed, he follows the careers of friends who become incredibly successful businessmen. One is a husband-and-wife team who open up a restaurant that eventually becomes a franchise. Another is the owner of a successful mineral water company that later goes on to merge with a European company. Li also navigates us through failures, like a cousin who had a temporary big hit with a billiards hall but never struck it rich, or a woman in a spa who had dreams of making it big but never got there.

Li considers all of these stories to be part of the Chinese tapestry of hard work and achievement in the capitalist system. Sure, there is grumbling from factory workers he interviews about giving up their "iron bowl" (guarantee of employment) for a "clay bowl" system (market economy). However, Li spends only a little time with Shan Guoyong, the head of Da Shan mineral water that later merged with Nestle', in terms of introspection. There are a few pages where Shan wonders if all of this consumerism is really worth the trouble, and how at one time in his life all he wanted was a bicycle. Of course, those concerns are shoved aside when it comes time to merge with Nestle', and Li is content to let those feelings go. Indeed, the look we get at a Dashan corporate retreat reveal the same kind of collectivism and loyalty oaths that were given to Mao, only now they were directed toward a corporate leader!

The whole philosophy of the book is very much "the past is the past". This was very much the attitude espoused by his father, who preferred not to talk or think about his time in prison but instead move on in his new government post. The eras that come under the greatest criticism, like the Cultural Revolution, are criticized not so much for the human rights atrocities but rather how it destabilized China and left them way behind the rest of the world. Indeed, while Li admitted some nostalgia for the simple China of his childhood, he revealed that he felt "like we (China) weren't there; everything in the world happened without us." In other words, we once again go back to the Deng doctrine of "Development is our first priority". As Li describes it, it's the only priority.

This leads to an interstitial scene where Li and Otie' argue about how best to present his view on the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Otie' stresses to him the importance of this event to Western readers, and Li is resistant, because he said that he wasn't anywhere near Beijing, only listened to the reports on the radio and has no idea what actually happened. Because he "didn't personally suffer", it wasn't something that was really part of his story like the Cultural Revolution, Great Leap Forward, etc. If that sounds like a cop-out, Li goes on to further give his real opinion on the matter. He notes that while he understands that lives were lost and people suffered, he considered the event within the context of Chinese history. Essentially, he was tired of China being a whipping boy for foreign interests and invaders. He was tired of instability. He was tired of being behind the industrialized nations of the world. The most salient quote is "China needs order and stability. The rest is secondary." The past is the past. Development is the first priority.

It's a statement that makes a degree of sense within the context of a countryman who suffered during the prior youth revolution (indeed, some women in his story fear the events of the protests as the potential return of the Red Guard). It's a statement that makes sense when you consider his pride that China became a world economic leader, and he takes shots at both the US and Europe for how they managed to accomplish this through force of arms and/or old money. It is disappointing, however, to see an intelligent man like Li who fancies himself a moralist in rooting out corruption to simply toss aside human rights and freedoms as expendable when the corporate well-being of China is involved. It is a kind of moral compartmentalization that reeks of hypocrisy, the same kind of hypocrisy he faced (and was part of) during the Cultural Revolution. It values dogma (or progress) over humanity. The past can't really be left behind for Li, because China is reliving and perpetuating it in a different form, one that may be dressed up with technology and civic pride, but ultimately has the same price: human misery. Li's amazing skill with a brush conjures up human misery at a visceral level when it is convenient (people dying of famine during the Great Leap Forward) and glosses over everything else when it's not. The nostalgia-soaked final sequence with his mother speaks to Li's skill in depicting the warmth of their relationship but also puts a bow on the ways in which A Chinese Life acts as propaganda for the China of the 21st century, celebrating its achievements while downplaying its flaws.

This is the blog of comics critic Rob Clough. I have writings elsewhere at SOLRAD.co, TCJ.com and a bunch more. I read and review everything sent to me eventually, especially minicomics. My address is: Rob Clough 881 Martin Luther King Junior King Blvd Apt 10 i Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Brit Comics: Simon Moreton's Smoo 7 and Twitching

Simon Moreton's seventh issue of Smoo continues in his recent, ultra-minimalist style of drawing. Moreton's comics tend to be concerned with the act of walking and landscapes as a kind of mental clearinghouse. Abstracting that walk and the view on that walk down to a few essential lines is a way of digesting and making sense of one's thoughts above all else. In this issue, he returns to his childhood home and devoted three separate mini-volumes to three different views of a particular path taken. Of course, the comic is more than the walk and more than the view: it's the emotions that arise as a result of being in a particular place at a particular time. Moreton avoids the whiff of simple nostalgia or sentimentality while acknowledging the deep grooves growing up in a particular place leaves on a person.

The mini actually begins with a letter from Moreton to the readers talking about the process of making the comic. He tries to get the reader to understand some of the more visceral conditions regarding the environment: cold giving way to sudden warmth, the threat of rain. That's followed by a map/poem, where a map of his home (labeled the way a kid might, with landmarks like "Old Pond" and "Our House") is intercut by text interact in clever ways, like a particular road labeled as "the road that takes you from here to there, forever" and a river labeled as "the Ledwyche flows through our woods...my heart in grassy patchwork". The map is really the closest Moreton gets to nostalgia, and he keeps it short.

The next comic is a silent one; it details a walk in an old neighborhood. Moreton draws the sky and trees but is also interested in seeing how old landmarks have changed, drawing buildings for sale. His drawings are wonderfully minimalist; his own self-caricature is simply a round circle for a head and two slightly curving lines under the circle representing his body. He wants to represent himself as present in this walk, as part of the environment, even if he's just a small part of it. At the end, he comments on what's different about his neighborhood.

The next comic begins with the phrase "This place is in my bones" as he recalls trying to run away once and then discusses his urge to want to run away. Moreton's battles with depression have always been a sub-theme of his comics, and this mini is the one that addresses it. The most compelling sequence comes when Moreton starts staring at the sky and clouds until his mind goes blank with several pages of no markings whatsoever. He confesses that he fights "the blues", but finds himself back in the same place emotionally, "the same sky" that he used to stare at in his darkest moments.

The final comic is about his memories of the old neighborhoods and haunts and the vague way they play in his mind; he notes "all my memories are myths" when he thinks of remembering a ball of light moving past him while walking down a hill. His memory of the woods is especially lovely, with drawings of far-off birds singing being replaced by simple, small and empty word balloons. The best feature was of "Caynham Court", an old, abandoned building that made for a myth-making playground for Moreton and his brother. Even with sketchy, abstracted drawings, Moreton gets at the sense of decay, the play of light and shadow, and features like a fake bookshelf that revealed a genuine secret passage. Revisiting these places now is less a matter of nostalgia than in thinking about one's own personal mythology and the ways in which it provided comfort as well as inculcate anxiety.

I also wanted to mention a comic Moreton did for SPX 2013 with Warren Craghead, Twitching. It's a flip book, and Moreton's half is based on a picture that Craghead dew of a man standing outside using a camera with a telescopic lens. Moreton transformed that into a story of a man trying to get the perfect angle for a photo of a bird, only he can't quite capture it before it decides to fly away.The last panel/page, where the tiny figure of the man walks away from the camera in frustration while we see a wide swath of nature, is both funny and indicative of the difficulty of trying to frame nature. The Moreton-written "Blinking" is drawn by Craghead and uses a different approach: a thick and sometimes sloppy line, scribbles and other spontaneous imagery. It's all to depict the sensation of being bombarded by different kinds of light, and like the first story, we often see the point of view directly from the eyes of the narrators. Craghead's approach is visceral and immersive, while Moreton's approach aims at expressing the outlines of things as they are quickly observed. Both are beautiful in their own way.

The mini actually begins with a letter from Moreton to the readers talking about the process of making the comic. He tries to get the reader to understand some of the more visceral conditions regarding the environment: cold giving way to sudden warmth, the threat of rain. That's followed by a map/poem, where a map of his home (labeled the way a kid might, with landmarks like "Old Pond" and "Our House") is intercut by text interact in clever ways, like a particular road labeled as "the road that takes you from here to there, forever" and a river labeled as "the Ledwyche flows through our woods...my heart in grassy patchwork". The map is really the closest Moreton gets to nostalgia, and he keeps it short.

The next comic is a silent one; it details a walk in an old neighborhood. Moreton draws the sky and trees but is also interested in seeing how old landmarks have changed, drawing buildings for sale. His drawings are wonderfully minimalist; his own self-caricature is simply a round circle for a head and two slightly curving lines under the circle representing his body. He wants to represent himself as present in this walk, as part of the environment, even if he's just a small part of it. At the end, he comments on what's different about his neighborhood.

The next comic begins with the phrase "This place is in my bones" as he recalls trying to run away once and then discusses his urge to want to run away. Moreton's battles with depression have always been a sub-theme of his comics, and this mini is the one that addresses it. The most compelling sequence comes when Moreton starts staring at the sky and clouds until his mind goes blank with several pages of no markings whatsoever. He confesses that he fights "the blues", but finds himself back in the same place emotionally, "the same sky" that he used to stare at in his darkest moments.

The final comic is about his memories of the old neighborhoods and haunts and the vague way they play in his mind; he notes "all my memories are myths" when he thinks of remembering a ball of light moving past him while walking down a hill. His memory of the woods is especially lovely, with drawings of far-off birds singing being replaced by simple, small and empty word balloons. The best feature was of "Caynham Court", an old, abandoned building that made for a myth-making playground for Moreton and his brother. Even with sketchy, abstracted drawings, Moreton gets at the sense of decay, the play of light and shadow, and features like a fake bookshelf that revealed a genuine secret passage. Revisiting these places now is less a matter of nostalgia than in thinking about one's own personal mythology and the ways in which it provided comfort as well as inculcate anxiety.

I also wanted to mention a comic Moreton did for SPX 2013 with Warren Craghead, Twitching. It's a flip book, and Moreton's half is based on a picture that Craghead dew of a man standing outside using a camera with a telescopic lens. Moreton transformed that into a story of a man trying to get the perfect angle for a photo of a bird, only he can't quite capture it before it decides to fly away.The last panel/page, where the tiny figure of the man walks away from the camera in frustration while we see a wide swath of nature, is both funny and indicative of the difficulty of trying to frame nature. The Moreton-written "Blinking" is drawn by Craghead and uses a different approach: a thick and sometimes sloppy line, scribbles and other spontaneous imagery. It's all to depict the sensation of being bombarded by different kinds of light, and like the first story, we often see the point of view directly from the eyes of the narrators. Craghead's approach is visceral and immersive, while Moreton's approach aims at expressing the outlines of things as they are quickly observed. Both are beautiful in their own way.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Punchable Face: Petty Theft

Pascal Girard goes yet deeper into the realm of squirm humor with a protagonist who goes from being pathetic and unlikable and skates into loathsome territory. Some have invoked Larry David's name when talking about Girard's comics, but David's "social assassin" self-caricature in his Curb Your Enthusiasm TV show is always an active agent in his life. With Girard in comics like Reunion and his new Petty Theft, he's more like a grown-up Charlie Brown. He's constantly defeated by life, but so many of his problems are a result of his own passive (and sometimes passive-aggressive) behavior. There's a touch of late-era Charles Schulz in Girard's line: his figures are cute, his line is thin to the point of being fragile and wobbly and there's a tremendous understanding and use of compact space and body language in order to generate slapstick gags. The lack of border panels only serves to emphasize the fragility of the line and how much negative space there is on each page. I have no doubts as to Girard's skill as a cartoonist nor any regarding his storytelling. One does wonder about a cartoonist whose self-caricature not only defies the reader to sympathize with him, but actively made me as a reader want to punch him repeatedly in the face.

Part of that is a result of the way Girard draws his self-caricature. With the stooped posture, oversized glasses, huge dot eyes, and oversized chin & nose, he's a sort of walking "kick me" sign. He's both the schlemeil and the schlimazel, to put it in Yiddish terms; in other words, he's the cause of accidents and also the recipient of bad luck. In this book, Girard is at a particular low point after a break-up of a long-term relationship; already a neurotic narcissist to begin with, his self-worth is in desperate need of a pick-me-up. He's couch-surfing with a friend, wants to abandon cartooning in favor of a more manly career like welding and even ponders going back to school. He's the epitome of the "first world problems" meme and so helplessly bourgeois that he can't see beyond his own ridiculous self-pity. When he's a bookstore and spots a pretty girl shoplifting a book that he drew, it launches him into the truly absurd career of "detective", as he starts following the girl around.

Girard makes fellow autobio cartoonist Joe Matt look confident, secure and healthy. Like Joe Matt, Girard is fascinated by the limits of breaking the social compact and engaging in squirm humor. That humor of awkwardness is at its zenith whenever Girard is following the thief around, daydreaming about first having sex with her and then having babies with her (!). He manages to contrive showing up at the cafe' at which she works and eventually ask her out on a date. Girard loves starting a premise and then throwing on as many crazy obstacles as possible in the path of that premise. For example, a date with the girl where he promises to cook her dinner is hindered by an eye injury incurred at his welding job, which makes it difficult for him to see, much less cook. After botching a kiss, Girard bumps his head into a shelf. That's after he carried a giant paper mache' head of his ex-girlfriend downstairs and literally bumps into the thief.

There is an eventual confrontation between Girard and the woman about her thievery and the various "noble" things he does to make up for it. Of course, she has other bizarre tics, like laughing loudly and inappropriately at comments she makes, not to mention her near sociopathic willingness to steal books from anyone and everyone. Naturally, Girard winds up with her in the end, healthy relationships be damned. Girard's self-flagellatory depiction, his masterful use of slapstick and the page design all serve to heighten discomfort. Petty Theft is a hundred page ride of awkwardness that never lets up, never encourages us to sympathize with its lead while never punishing him for his behavior in any direct way. In a sense, living in his own skin is its own punishment.

Part of that is a result of the way Girard draws his self-caricature. With the stooped posture, oversized glasses, huge dot eyes, and oversized chin & nose, he's a sort of walking "kick me" sign. He's both the schlemeil and the schlimazel, to put it in Yiddish terms; in other words, he's the cause of accidents and also the recipient of bad luck. In this book, Girard is at a particular low point after a break-up of a long-term relationship; already a neurotic narcissist to begin with, his self-worth is in desperate need of a pick-me-up. He's couch-surfing with a friend, wants to abandon cartooning in favor of a more manly career like welding and even ponders going back to school. He's the epitome of the "first world problems" meme and so helplessly bourgeois that he can't see beyond his own ridiculous self-pity. When he's a bookstore and spots a pretty girl shoplifting a book that he drew, it launches him into the truly absurd career of "detective", as he starts following the girl around.

Girard makes fellow autobio cartoonist Joe Matt look confident, secure and healthy. Like Joe Matt, Girard is fascinated by the limits of breaking the social compact and engaging in squirm humor. That humor of awkwardness is at its zenith whenever Girard is following the thief around, daydreaming about first having sex with her and then having babies with her (!). He manages to contrive showing up at the cafe' at which she works and eventually ask her out on a date. Girard loves starting a premise and then throwing on as many crazy obstacles as possible in the path of that premise. For example, a date with the girl where he promises to cook her dinner is hindered by an eye injury incurred at his welding job, which makes it difficult for him to see, much less cook. After botching a kiss, Girard bumps his head into a shelf. That's after he carried a giant paper mache' head of his ex-girlfriend downstairs and literally bumps into the thief.

There is an eventual confrontation between Girard and the woman about her thievery and the various "noble" things he does to make up for it. Of course, she has other bizarre tics, like laughing loudly and inappropriately at comments she makes, not to mention her near sociopathic willingness to steal books from anyone and everyone. Naturally, Girard winds up with her in the end, healthy relationships be damned. Girard's self-flagellatory depiction, his masterful use of slapstick and the page design all serve to heighten discomfort. Petty Theft is a hundred page ride of awkwardness that never lets up, never encourages us to sympathize with its lead while never punishing him for his behavior in any direct way. In a sense, living in his own skin is its own punishment.

Monday, July 28, 2014

The Madness of Civilization: Goddamn This War!

World War I was a subject that so enraged Jacques Tardi that he followed up his powerful It Was The War Of The Trenches with Goddamn This War! The former book was a series of disconnected vignettes that jumped around in time and gave the reader the simple blood and guts of the war: powerful new technologies that bewildered unprepared soldiers and made conventional combat obsolete; opportunistic officers; hypocritical and out-of-touch generals and leaders espousing patriotism in meaningless conflict; and a war engineered to further the rich and no one else. In Goddamn This War!, Tardi adds more structure and labors to create a narrative that follow a more linear temporal path. Each chapter covers a single year of the war, and Tardi enlisted the aid of World War I expert Jean-Pierre Verney to write an extensive appendix to the book covering the entire scope of the war on a similar year-by-year basis. Once again, Fantagraphics' beautiful design work makes the book look as good as possible; it was one of the last books that Kim Thompson edited before he died.

What's most remarkable about bout the first-person narrative of the unnamed French soldier, as well as the highly detailed and opinionated essays by Verney is that World War I made no sense whatsoever, and even the soldiers knew it. There was no way to explain it without using the language of nationalism and jingoism. It was a vestigial attempt at fighting the same European wars for territory that had been fought for a thousand years, only the industrial revolution and the advent of market capitalism transformed it beyond the abilities of even the military's leaders to understand and shape in a meaningful way. It was a war of propaganda, of industry looking to expand, of nationalism whipped up in popular culture for catastrophic ends. Beyond the war's general pointlessness, Europe was turned into a mass grave by dint of the sheer stubbornness of its military leaders. Several of France's generals in particular simply didn't understand that hurling thousands of French soldiers at well-fortified German positions only guaranteed creating piles of French corpses. Add to this idiocy on both sides the notion that the war would be over in a few weeks only added to their recklessness with the troops. This was no longer the 100 Year War, the Thirty Year War or even the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Wars were no longer fought on level fields with horses. WWI introduced such horrors as mustard gas, the flamethrower, advanced heavy artillery, air combat, advanced submarine use, grenades and tanks.

Tardi, through his sardonic and cynical narrator, explores the soldier's experience. The soldier on the ground literally had no idea what was going on in terms of strategy. He simply charged up a hill and attacked when told to and otherwise tried to stay alive in his trench. The war simply became unremitting boredom followed by chaos, frenzied orders and the hope for survival. All of this took place in mud and snow, in the mountains or underground, in the air and on the sea. The soldiers were ill-equipped to fight against new and frightening technology. Indeed, the Germans said after the war that their enemies won not because of their superior ability or strategy, but because of "General Tank". Even the highly-disciplined German lines couldn't resist the British tanks en masse.

The best way to describe the conflict for the soldiers, especially from Tardi's narrative, is that it was like being sentenced to hell for five years--if you were lucky to live that long. When the armistice came, the soldiers were in disbelief that hell was now over. Tardi noted that their joy was understandable if misplaced, since so many lives had been lost and so much of France's infrastructure had been destroyed. Tardi's soldier is seething with anger throughout the book and openly resentful of his officers while having sympathy for the enemies, "Les Boches". There's a particular German soldier he sees early in the war, when they managed to spare each other, and he often wonders what's become of him.

Tardi's mastery of body language is a perfect fit with his slightly cartoony figure drawing. There's almost a touch of a bigfoot drawing style that's a touchstone of French cartooning. At the same time, he's fastidious with regard to details: he wants to know exactly what each weapon, each uniform, each battle looked like in real life. Despite that penchant for detail, the comic never bogs down into static photorealism. Instead, there's a slow, lurching quality to the narrative that gets across the stop-and-go nature of the combat. His use of color is a key storytelling technique. While starting off with all sorts of vibrant reds, blues and greens, the book eventually gives way to trench-gray and mud-brown, with splashes of red thrown in when blood's involved. He also highlights flags and officers as they appear, showing how incongruous these symbols and people are with regard to actual combat.

Tardi is actually fairly restrained with regard to gore and violence throughout most of the book. There are the occasional scenes of a soldier trying to hold in his guts or a soldier with his brains blown out, but Tardi chooses to focus on the living more than the dead. That's until the last two pages of his chapter on 1918 (the last year of the war): they feature 3 x 3 grids where every panel is that of the disfigured face of a different soldier. These are faces deformed and reconstructed (as much as patchwork medicine would allow) by shrapnel, bullets and bombs. Each page is wordless, with each man in uniform. It's a powerful and even stomach-churning pair of pages, and it's a challenge for the reader to actually look at each panel in detail.

In the 1919 chapter, each page is stacked with three horizontal panels. Each panel details a different person's life and experience in the war. There's a Senegalese POW captured by the Germans, wondering what this white man's going to do to him. There's a soldier feeding his buddy stuck in mud with a long stick, as he slowly sinks. There's a nurse desperately trying to help tend to soldiers while wondering about her own brother. There's a piano in a wrecked building that's been booby-trapped by the Germans. There are children forced to work in German mines because there's no one else left. And so on, until we finally meet our narrator, sitting in a bar, missing one hand. It's a virtuoso piece that avoids some of It Was The War Of The Trenches' tendency to be a bit too on-the-nose with regard to its anti-war sentiment. Goddamn This War!, while going into great detail with regard to the conflict in a way that can be understood and compartmentalized, is less about war and more about madness. It's about the madness of what Kant would say is treating other human beings as a means to an end. It's about the madness of reifying arbitrary borders into a concrete identity called a "nation". It's about the total absurdity of being caught up in these situations, and how absurdity breeds tragedy when guns and uniforms are involved. It's about the danger of dogma when it doesn't take human lives into account. It's the work of a mature cartoonist whose exasperated outrage has given way to a simmering and more nuanced cynicism.

What's most remarkable about bout the first-person narrative of the unnamed French soldier, as well as the highly detailed and opinionated essays by Verney is that World War I made no sense whatsoever, and even the soldiers knew it. There was no way to explain it without using the language of nationalism and jingoism. It was a vestigial attempt at fighting the same European wars for territory that had been fought for a thousand years, only the industrial revolution and the advent of market capitalism transformed it beyond the abilities of even the military's leaders to understand and shape in a meaningful way. It was a war of propaganda, of industry looking to expand, of nationalism whipped up in popular culture for catastrophic ends. Beyond the war's general pointlessness, Europe was turned into a mass grave by dint of the sheer stubbornness of its military leaders. Several of France's generals in particular simply didn't understand that hurling thousands of French soldiers at well-fortified German positions only guaranteed creating piles of French corpses. Add to this idiocy on both sides the notion that the war would be over in a few weeks only added to their recklessness with the troops. This was no longer the 100 Year War, the Thirty Year War or even the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Wars were no longer fought on level fields with horses. WWI introduced such horrors as mustard gas, the flamethrower, advanced heavy artillery, air combat, advanced submarine use, grenades and tanks.

Tardi, through his sardonic and cynical narrator, explores the soldier's experience. The soldier on the ground literally had no idea what was going on in terms of strategy. He simply charged up a hill and attacked when told to and otherwise tried to stay alive in his trench. The war simply became unremitting boredom followed by chaos, frenzied orders and the hope for survival. All of this took place in mud and snow, in the mountains or underground, in the air and on the sea. The soldiers were ill-equipped to fight against new and frightening technology. Indeed, the Germans said after the war that their enemies won not because of their superior ability or strategy, but because of "General Tank". Even the highly-disciplined German lines couldn't resist the British tanks en masse.

The best way to describe the conflict for the soldiers, especially from Tardi's narrative, is that it was like being sentenced to hell for five years--if you were lucky to live that long. When the armistice came, the soldiers were in disbelief that hell was now over. Tardi noted that their joy was understandable if misplaced, since so many lives had been lost and so much of France's infrastructure had been destroyed. Tardi's soldier is seething with anger throughout the book and openly resentful of his officers while having sympathy for the enemies, "Les Boches". There's a particular German soldier he sees early in the war, when they managed to spare each other, and he often wonders what's become of him.

Tardi's mastery of body language is a perfect fit with his slightly cartoony figure drawing. There's almost a touch of a bigfoot drawing style that's a touchstone of French cartooning. At the same time, he's fastidious with regard to details: he wants to know exactly what each weapon, each uniform, each battle looked like in real life. Despite that penchant for detail, the comic never bogs down into static photorealism. Instead, there's a slow, lurching quality to the narrative that gets across the stop-and-go nature of the combat. His use of color is a key storytelling technique. While starting off with all sorts of vibrant reds, blues and greens, the book eventually gives way to trench-gray and mud-brown, with splashes of red thrown in when blood's involved. He also highlights flags and officers as they appear, showing how incongruous these symbols and people are with regard to actual combat.

Tardi is actually fairly restrained with regard to gore and violence throughout most of the book. There are the occasional scenes of a soldier trying to hold in his guts or a soldier with his brains blown out, but Tardi chooses to focus on the living more than the dead. That's until the last two pages of his chapter on 1918 (the last year of the war): they feature 3 x 3 grids where every panel is that of the disfigured face of a different soldier. These are faces deformed and reconstructed (as much as patchwork medicine would allow) by shrapnel, bullets and bombs. Each page is wordless, with each man in uniform. It's a powerful and even stomach-churning pair of pages, and it's a challenge for the reader to actually look at each panel in detail.

In the 1919 chapter, each page is stacked with three horizontal panels. Each panel details a different person's life and experience in the war. There's a Senegalese POW captured by the Germans, wondering what this white man's going to do to him. There's a soldier feeding his buddy stuck in mud with a long stick, as he slowly sinks. There's a nurse desperately trying to help tend to soldiers while wondering about her own brother. There's a piano in a wrecked building that's been booby-trapped by the Germans. There are children forced to work in German mines because there's no one else left. And so on, until we finally meet our narrator, sitting in a bar, missing one hand. It's a virtuoso piece that avoids some of It Was The War Of The Trenches' tendency to be a bit too on-the-nose with regard to its anti-war sentiment. Goddamn This War!, while going into great detail with regard to the conflict in a way that can be understood and compartmentalized, is less about war and more about madness. It's about the madness of what Kant would say is treating other human beings as a means to an end. It's about the madness of reifying arbitrary borders into a concrete identity called a "nation". It's about the total absurdity of being caught up in these situations, and how absurdity breeds tragedy when guns and uniforms are involved. It's about the danger of dogma when it doesn't take human lives into account. It's the work of a mature cartoonist whose exasperated outrage has given way to a simmering and more nuanced cynicism.

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Various Causes and Promos: Porcellino, Agostino, Cupcake Award, Mini of the Month Club, Mini-Sweep

A few causes, opportunities and promotions that have been passed my way:

The great John Porcellino had a documentary made about him by Dan Stafford titled Root Hog Or Die. Stafford is running a kickstarter campaign to produce DVDs for the film, a shorter version of which will screen at various places this year, including SPX. The goal is pretty affordable ($5000) and this will be a must-see for fans of John P. Here's the Kickstarter link.

Author Lauren Agostino passed on a note to promote her new book (with A.L. Newberg), Holding Kryptonite: Truth, Justice and America's First Superhero. The book came about due to her stumbling across legal papers and other private correspondence between Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman. Check it out here.

Brian Cremins of CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comics Expo), one of the fine alt-comix shows in the US, sent me a note announcing the Cupcake Award. This is a $250 cash prize to print a new minicomic and a free half-table at CAKE to sell their comics. Here's the FAQ, but hurry with the application: the deadline is August 31st.

Australia's Andrew Fulton wrote to me about his Minicomics of the Month Club. The latest round of subscriptions ends on July 31st, so act quickly. Each month, a subscriber gets a new minicomic, including work by CCS grads Ben Juers and Bailey Sharp. Check it out!

Finally, I wanted to link to Foxing Quarterly's blog, where my Thursday column "Mini-Sweep" continues to appear. I've recently written about Whit Taylor's The Anthropologists, Elijah Brubaker's Reich #11, Asher Craw's Hungry Summer and Olga Volozova's The Golem of Gabirol.

Author Lauren Agostino passed on a note to promote her new book (with A.L. Newberg), Holding Kryptonite: Truth, Justice and America's First Superhero. The book came about due to her stumbling across legal papers and other private correspondence between Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman. Check it out here.

Brian Cremins of CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comics Expo), one of the fine alt-comix shows in the US, sent me a note announcing the Cupcake Award. This is a $250 cash prize to print a new minicomic and a free half-table at CAKE to sell their comics. Here's the FAQ, but hurry with the application: the deadline is August 31st.

Australia's Andrew Fulton wrote to me about his Minicomics of the Month Club. The latest round of subscriptions ends on July 31st, so act quickly. Each month, a subscriber gets a new minicomic, including work by CCS grads Ben Juers and Bailey Sharp. Check it out!

Finally, I wanted to link to Foxing Quarterly's blog, where my Thursday column "Mini-Sweep" continues to appear. I've recently written about Whit Taylor's The Anthropologists, Elijah Brubaker's Reich #11, Asher Craw's Hungry Summer and Olga Volozova's The Golem of Gabirol.

Saturday, July 26, 2014

Comics Journal Index 2011

Here are all of the reviews, features and interviews I wrote for TCJ.com in 2011. Note that the website went through a reboot in March of 2011, with articles from prior to that date appearing on the "classic" TCJ site. My favorites from this year include my reviews of Habibi, Gay Genius, The Collected John G Miller, The Heavy Hand and Habitat #2, as well as my feature on Dave Kiersh. I think both of the interviews featured here (Mike Dawson and Mari Naomi) are worth reading.

Papercutter #17, edited by Greg Means 12/21/2011

Gay Genius, edited by Annie Murphy 12/19/2011

Freddy Stories, by Melissa Mendes 11/30/2011

Pope Hats #2, by Ethan Rilly 11/22/2011

Mark Twain's Autobiography, by Michael Kupperman 11/16/2011

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton 11/11/2011

Habibi, by Craig Thompson 11/4/2011

The Burden of Promise: Fusion and the Comics of Michael DeForge 10/5/2011

Collected John G Miller, 1990-99 9/30/2011

Little Nothings V4, by Lewis Trondheim 9/13/2011

The Mike Dawson Interview 9/8/2011

Americus, by MK Reed & Jonathan Hill 9/2/2011

Too Small To Fail, by Keith Knight 8/25/2011

I Will Bite You!, by Joseph Lambert 8/17/2011

Island of 100000 Graves, by Jason & Fabien Vehlmann 8/8/2011

Huntington, WV 'On The Fly', by Harvey Pekar & Summer McClinton 7/22/2011

Level Up, by Gene Luen Yang and Thien Pham 7/18/2011

Sundays 4, Forever Changes, edited by Chuck Forsman 7/8/2011

Lost Boy: The Comics of Dave Kiersh 6/30/2011

The Next Day, by John Porcellino, Paul Peterson, Jason Gilmore 6/28/2011

Willie & Joe: Back Home, by Bill Mauldin 6/18/2011

Dungeon Monstres, Vol 4, by Lewis Trondheim, Joann Sfar 6/9/2011

The Heavy Hand, by Chris Cilla 6/3/2011

Melvin Monster Volume 3, by John Stanley 5/18/2011

Habitat #2, by Dunja Jankovic 5/6/2011

Top 25 Minis of 2010 5/4/2011

Blammo #7, by Noah Van Sciver 4/28/2011

Approximate Continuum Comics, by Lewis Trondheim 4/15/2011

Eric Reynolds and the End of Mome 4/12/2011

Gazeta, edited by Lisa Mangum 4/8/2011

The Latest From Revival House 3/16/2011

Switching Between Languages: An Interview With MariNaomi 3/15/2011

Lewis and Clark, by Nick Bertozzi. 3/2/2011

Twilight of the Assholes, by Tim Kreider. 2/28/2011

Interiorae #4, by Gabriella Giandella . 2/26/2011

Grotesque #4, by Sergio Ponchionne. 2/23/2011

Niger #3, by Leila Marzocchi. 2/21/2011

Sammy The Mouse #3, by Zak Sally. 2/19/2011

The Broadcast, by Eric Hobbs & Noel Tuazon. 2/16/2011

Comics as Poetry 2: L. Nichols, Malcy Duff 2/14/2011

Comics as Poetry 1: Jason T Miles, Aaron Cockle 2/12/2011

Mineshaft #26 2/9/2011

Minicomics: Candy or Medicine, Dina Kelberman, Kel Crum, Lydia Conklin, Desmond Reed 2/7/2011

Nipper, by Doug Wright 2/5/2011

Solipsistic Pop, Volume 3 2/3/2011

Tubby V 1, by John Stanley 2/2/2011

Nancy V 2, by John Stanley 1/31/2011

Minicomics from Alexis Frederick-Frost, Sean Ford and Noel Freibert 1/29/2011

Curio Cabinet, by John Brodowski 1/28/2011

Scenes From An Impending Marriage, by Adrian Tomine 1/26/2011

Toner by Jonathan Wayshak; Boston Gastronauts, by C. Che Salazar; Negative Too by Phonzie Davis; The Short Term, by Nick Jeffrey; Interview With Delicious Storm, by Si-Yeon Min 1/24/2011

Big Questions #15, by Anders Nilsen 1/22/2011

Berlin #17, by Jason Lutes 1/19/2011

Palookaville #20, by Seth 1/17/2011

Borderland by Dan Archer, World War III Illustrated #41 1/15/2011

Hotwire V 3 1/12/2011

Eden, by Pablo Holmberg 1/10/2011

Minicomics: Sacha Mardou, Kyle Baddeley, Ryan Cecil Smith 1/8/2011

Minicomics: Francois Vigneault, Johnathan Baylis, ES Fletschinger 1/5/2011

The Whale, by Aidan Koch 1/3/2011

1-800-MICE #5, by Matthew Thurber

Papercutter #17, edited by Greg Means 12/21/2011

Gay Genius, edited by Annie Murphy 12/19/2011

Freddy Stories, by Melissa Mendes 11/30/2011

Pope Hats #2, by Ethan Rilly 11/22/2011

Mark Twain's Autobiography, by Michael Kupperman 11/16/2011

Hark! A Vagrant by Kate Beaton 11/11/2011

Habibi, by Craig Thompson 11/4/2011

The Burden of Promise: Fusion and the Comics of Michael DeForge 10/5/2011

Collected John G Miller, 1990-99 9/30/2011

Little Nothings V4, by Lewis Trondheim 9/13/2011

The Mike Dawson Interview 9/8/2011

Americus, by MK Reed & Jonathan Hill 9/2/2011

Too Small To Fail, by Keith Knight 8/25/2011

I Will Bite You!, by Joseph Lambert 8/17/2011

Island of 100000 Graves, by Jason & Fabien Vehlmann 8/8/2011

Huntington, WV 'On The Fly', by Harvey Pekar & Summer McClinton 7/22/2011

Level Up, by Gene Luen Yang and Thien Pham 7/18/2011

Sundays 4, Forever Changes, edited by Chuck Forsman 7/8/2011

Lost Boy: The Comics of Dave Kiersh 6/30/2011

The Next Day, by John Porcellino, Paul Peterson, Jason Gilmore 6/28/2011

Willie & Joe: Back Home, by Bill Mauldin 6/18/2011

Dungeon Monstres, Vol 4, by Lewis Trondheim, Joann Sfar 6/9/2011

The Heavy Hand, by Chris Cilla 6/3/2011

Melvin Monster Volume 3, by John Stanley 5/18/2011

Habitat #2, by Dunja Jankovic 5/6/2011

Top 25 Minis of 2010 5/4/2011

Blammo #7, by Noah Van Sciver 4/28/2011

Approximate Continuum Comics, by Lewis Trondheim 4/15/2011

Eric Reynolds and the End of Mome 4/12/2011

Gazeta, edited by Lisa Mangum 4/8/2011

The Latest From Revival House 3/16/2011

Switching Between Languages: An Interview With MariNaomi 3/15/2011

Lewis and Clark, by Nick Bertozzi. 3/2/2011

Twilight of the Assholes, by Tim Kreider. 2/28/2011

Interiorae #4, by Gabriella Giandella . 2/26/2011

Grotesque #4, by Sergio Ponchionne. 2/23/2011

Niger #3, by Leila Marzocchi. 2/21/2011

Sammy The Mouse #3, by Zak Sally. 2/19/2011

The Broadcast, by Eric Hobbs & Noel Tuazon. 2/16/2011

Comics as Poetry 2: L. Nichols, Malcy Duff 2/14/2011

Comics as Poetry 1: Jason T Miles, Aaron Cockle 2/12/2011

Mineshaft #26 2/9/2011

Minicomics: Candy or Medicine, Dina Kelberman, Kel Crum, Lydia Conklin, Desmond Reed 2/7/2011

Nipper, by Doug Wright 2/5/2011

Solipsistic Pop, Volume 3 2/3/2011

Tubby V 1, by John Stanley 2/2/2011

Nancy V 2, by John Stanley 1/31/2011

Minicomics from Alexis Frederick-Frost, Sean Ford and Noel Freibert 1/29/2011

Curio Cabinet, by John Brodowski 1/28/2011

Scenes From An Impending Marriage, by Adrian Tomine 1/26/2011

Toner by Jonathan Wayshak; Boston Gastronauts, by C. Che Salazar; Negative Too by Phonzie Davis; The Short Term, by Nick Jeffrey; Interview With Delicious Storm, by Si-Yeon Min 1/24/2011

Big Questions #15, by Anders Nilsen 1/22/2011

Berlin #17, by Jason Lutes 1/19/2011

Palookaville #20, by Seth 1/17/2011

Borderland by Dan Archer, World War III Illustrated #41 1/15/2011

Hotwire V 3 1/12/2011

Eden, by Pablo Holmberg 1/10/2011

Minicomics: Sacha Mardou, Kyle Baddeley, Ryan Cecil Smith 1/8/2011

Minicomics: Francois Vigneault, Johnathan Baylis, ES Fletschinger 1/5/2011

The Whale, by Aidan Koch 1/3/2011

1-800-MICE #5, by Matthew Thurber

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Brit Comics: The Comix Reader

The Comix Reader is the brainchild of British cartoonist, Richard Cowdry. He edits and contributes material to each issue. Its format is that of a classic comics broadsheet; each issue is 24 pages and in full color. His stated purpose in publishing it was to revive the anything goes, "fun" and "free-spirited" nature of the underground press of the 60s and 70s. That's a line I've heard quite often from slightly older cartoonists in the US who decry literary comics and cartoonists and prefer their comics to be as id-soaked, vulgar and free-wheeling as possible. Naturally, there's room for all sorts of comics, but those that invoke the underground frequently have a chip on their shoulder while staking out their territory.

Fortunately, Cowdry abandons this rhetoric after the first issue and simply went about the business of recruiting a wide variety of artists to regularly contribute to the Reader. Having read the first five issues, it establishes a nice rhythm to see some artists return in issue after issue, while having more samples of work made me appreciate other artists more. Cowdry has made a sustained effort to recruit a number of female cartoonists and obviously has no editorial mandates as to what he wants each cartoonist to do. The result is a melange of gag strips, local/topical humor, autobio comics, whimsical fantasy strips, low-res drawings and highly detailed renderings. The Reader has gotten stronger from issue to issue, and that's a testament to each cartoonist obviously trying to contribute their best material and up their game in each subsequent installment. Rather than review particular issues, I thought I'd highlight some of the cartoonists who caught my eye. While this is a long list, there's still about a dozen other cartoonists published in the Reader who didn't draw my attention one way or another.

Richard Cowdry: Cowdry himself is an excellent and vicious satirist. Some of the strips here were reprinted in his Downtown collection, which I reviewed here.

Saban "Shabs" Sazin: The cartoony style of this artist emphasizes bold, sweeping expressions by his characters. Sazin smartly and amusingly addresses working-class woes as well as the experience of being an immigrant in the U.K. His thick line looks especially great soaking up color on a big page.

Lord Hurk: Hurk most closely resembles the underground cartoonists to which Cowdry refers than anyone else in the Reader. His comics are in turn bizarre, hilarious and imaginative as he imagines the adventures of the Lonely Bomb, Diamond Chops and misshapen superhero The Magnificent Orb. Hurk's chops are unassailable and his work looks especially effective in color. While he taps into that anarchic underground sensibility in terms of his ideas and wild visuals, he avoids scatology for scatology's sake; every gross gag is in service of the story or satire. His figures are grotesque, funny and distorted, but his work doesn't rest on grossing out the reader.

Kat Kon: Kon tends to work really big--like just four panels per huge page. That's because she likes to blow up faces and really zero in their weirder qualities. In issue #2, she works a bit smaller, but still with that thick line that emphasizes character expression and lots of spotting blacks. Issue #3 has one image where a woman has a shirt that says "I refuse to smile for no reason" and loads of dead bodies around her; it's a darkly amusing take on a persistent feminist issue that pervades any number of culture. The fifth issue reinforces this with her take on being a barista and the kinds of comments she gets. Kon isn't much one for metacommentary, letting her figures and images speak for themselves. The format certainly flatters her art and adds greatly to its punch.

Alex Potts: His comics took time to really grow on me, as he tends to use a 5 x 7 grid in each issue. That grid minimizes his art while pushing the reader through quickly, but his low-key narratives regarding the character Philip have a surprisingly dark tone to them. Potts reminds me a bit of Chris Ware in the way he uses small panels to his advantage and lets the reader figure out the implications of the character's story for themselves.

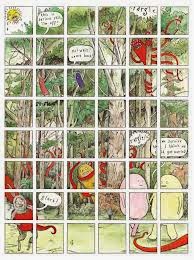

Steve Tillotson: Of all the artists in the Reader, Tillotson is the one who took the greatest advantage of the formal possibilities of working big. His trademark is using a grid that simultaneously depicts a single image and that breaks it up to allow individual actions by the characters. His rendering is superb, as he draws both cute & simple characters as well as lush backgrounds. I'm not sure I'd be up to seeing a book's worth of his strips, but that's what makes him perfect for an anthology.

Ellen Lindner: A long-time favorite of mine, Lindner uses her Reader space for autobio (which has always been funny and sharply observed) and splashes it with huge swaths of vivid color. Oranges, yellows, greens, pinks and purples all tend to dominate her comics here, grabbing the reader's eye while she relates witty and thoughtful anecdotes.

Sina Shamsavari: His autobio centers around relationships and loneliness as a gay man in London. His line varies from a bold, naturalistic style to a more fragile, angular look that incorporates splashes of color. I love the way he varies approaches from issue to issue. In some, he does a single narrative and in others, four 2 x 3 panel mini-narratives. All of them focus on the pros and cons of being alone, of being an outsider even in gay culture. The comics are philosophical and thoughtful rather than whiny, but one can still feel Shamsavari's(variously also known as Sina Evil and Sina Sparrow) the depths of his sadness. That's mitigated by the ways in which he finds to express himself. The sophistication of his autobio is a perfect balance for the sillier stuff in the Reader.

Paul O'Connell: O'Connell's biography of model and singer Sabrina in #1 was a strong piece, using photo-reference to create a narrative while giving it a "pop art" effect through the nonintuitive application of color. Less successful was a "clowns in hell" experiment with Addy Evenson; this page was dissonant to the point of incoherency.

Julia Homersham: Homersham appeared in the first two issues with a number of goofy gags that riff on inanimate objects like food or animals behaving as humans. The first issue features single-panel gags, while the second issue is all strips of various lengths. Homersham is heavy on both verbal and visual puns, and there are some groaners in there. In the context of the reader, her work acts as a nice palate cleanser for heavier work. Her "History of English Puddings" page is not strictly comics, but the nomenclature and explanation of many of these bizarre dishes is both bewildering and amusing.

Tobias Tak: Tak is a great draftsman who pulls out all the stops with his use of color. The actual content of his comics is usually self-consciously twee, which makes reading them a slog. They're like reading a Richard Sala comic without any of the bite or the brains and tend to act as a roadblock while reading the anthology. It's labored whimsy.

Gareth Brookes: His page about birds singing to humanity about its arrogance was one of the most overtly-precious, tedious and annoying lectures I've ever seen in comics. The birds are nicely-illustrated, but they're only illustrations and lie inert on the page.

Tim & Alex Levin: Their "Jones" gag strips, in issue after issue, are sloppy without any charm. The jokes themselves are easy pop cultural targets, dumb scatological humor, or bits of randomness that don't go anywhere.

Peter Lally: His take-off on the artist Banksy was silly, poorly-drawn and had an obvious punchline. Much better was "Taxi", a fascinating slice-of-life story (drawn white-on-black backgrounds) that reveals a lot about working-class taxi drivers and an older generation in general. The style Lally used was bold and eye-catching, instantly drawing me in.

Bernadette Bentley: Bentley writes, smart, funny and sharply-observed autobio comics. Her strip about being a guard in a museum and desperately trying to find things to do to stave off boredom is clever for her use of strike-outs in her text to couch meanings. The story about her mother trying to use art to draw out mentally handicapped people that was subsequently shot down by superiors was heart-breaking.

Barnath Richards: He did just one page for the Reader, but it's a doozy: a beautifully drawn and colored one-pager about remembering a TV show from his youth about a robot. In just three panels, he captures the vividness of this memory without wallowing too much in the nostalgia of the moment.

Hannah Eaton: Her densely rendered story about her grandfather hauling corpses for a living was funny and evocative of a different and often stranger era.

Jimi Gherkin: Gherkin's comics are mostly silly, but I thought his affectionate tribute to Harvey Pekar and R.Crumb in "The Jimi Gherkin Name Story" was effective both as homage and as a way of exploring his own past.

Elliot Baggott: Baggott is another artist who dove into the opportunity given to him by having such a big page with enormous relish. His first strip, a single illustration that follows a fox down a building and through a city, is a marvel of clear formal cleverness. His silent strip in #3, done in the style of stained glass, is a gag about how movable type transformed the world, complete with a plop take at the end. If his first strip was remarkable for its use of negative space, the second one is fascinating due to how the reader is dropped into a landscape entirely suffused with color. "Boss Talk" in #5 is a more conventional strip that's a takedown of thinly veiled sexism.

Bird: Bird's mediation on why we worship what we worship and the sheer weirdness of being alive in #3 was funny and thoughtful, and his thin line combined with a restrained use of color made it a highlight. Jokes about allergies and "Happy Days" in #4 could have been hacky, but they were so well-constructed that the set-ups were just as amusing as the punchlines; the character construction was completely different than his work in #3 but their rounded, roly-poly quality was entirely appropriate for this sort of joke.

Maartje Schalkx: Schalkx's strips are models of economy and efficiency, as they mostly depict just her head, and remove most of her facial features at that. There's one strip in particular where we see just her head on a pillow and her eyes open, staring at a man sleeping next to her with his eyes closed. She flips back and forth in sequence on a panel-free page, sparking a silent reverie about perhaps why she's there and who she happens to be sleeping next to. Another issue simply featured her head bouncing down the page, while another issue features her head interacting with other heads at an LGBT disco, where she's trying hard to pick someone up. That strip also features soft pastels in the background, adding to the ethereal feel of that particular scenario. Schalkx uses the entire page in smart ways that made seeing her work a pleasure in every issue.

Craig Burston: I'm not generally a fan of 8-bit style drawings, but Burston's "Low-Res Des" strips are funny because they make the formal qualities of the work part of the narrative. The strip about the fly (in an homage to the film The Fly) was especially amusing.

Ralph Kidson: Kidson's first strip was called "Big Balls Crow", which is about all you need to know about it. The rest of his work in the Reader is silly without otherwise being distinctive.

Sean Duffield: I found little to interest me in Duffield's work; when it wasn't mining scatological humor for its own sake, it seemed overly provincial. It was too locked into local, political and popular references to resonate with me, though perhaps that wouldn't be true of someone living in Britain.

Noelle Barby: Her autobio strip about encountering the forces of sexual debauchery (at last!) in high school was hilarious, as were the depictions of her particular sexual misadventures. Seeing Lust narrate her disappointing future sexual adventures in high school was also amusing, though Barby did at least hold out hope for herself for "life after high school".

James Parsons: Parson's first strip that sees football hooligans wearing the red cross on their faces was mostly clever because of the red crosses on the ambulances that arrive after the inevitable dust-up. His strip in #5 about developing a crush on the actress Sarah Douglas, who played the villainous Ursa in Superman II. It's the rare strip that's both intensely personal and dedicated to one's id but also finds ways to ridicule his own obsessions. The drawings themselves are hilarious--especially the cartoony ones of his penis.

Sally-Anne Hickman: Hickman's "SallyShinyStars" comic strip was a highlight of #5, detailing in grotesque and colorful fashion certain anecdotes about working in a market and the sort of customers she encountered. Her self-caricature is especially amusing.

Fortunately, Cowdry abandons this rhetoric after the first issue and simply went about the business of recruiting a wide variety of artists to regularly contribute to the Reader. Having read the first five issues, it establishes a nice rhythm to see some artists return in issue after issue, while having more samples of work made me appreciate other artists more. Cowdry has made a sustained effort to recruit a number of female cartoonists and obviously has no editorial mandates as to what he wants each cartoonist to do. The result is a melange of gag strips, local/topical humor, autobio comics, whimsical fantasy strips, low-res drawings and highly detailed renderings. The Reader has gotten stronger from issue to issue, and that's a testament to each cartoonist obviously trying to contribute their best material and up their game in each subsequent installment. Rather than review particular issues, I thought I'd highlight some of the cartoonists who caught my eye. While this is a long list, there's still about a dozen other cartoonists published in the Reader who didn't draw my attention one way or another.

Richard Cowdry: Cowdry himself is an excellent and vicious satirist. Some of the strips here were reprinted in his Downtown collection, which I reviewed here.

Saban "Shabs" Sazin: The cartoony style of this artist emphasizes bold, sweeping expressions by his characters. Sazin smartly and amusingly addresses working-class woes as well as the experience of being an immigrant in the U.K. His thick line looks especially great soaking up color on a big page.

Lord Hurk: Hurk most closely resembles the underground cartoonists to which Cowdry refers than anyone else in the Reader. His comics are in turn bizarre, hilarious and imaginative as he imagines the adventures of the Lonely Bomb, Diamond Chops and misshapen superhero The Magnificent Orb. Hurk's chops are unassailable and his work looks especially effective in color. While he taps into that anarchic underground sensibility in terms of his ideas and wild visuals, he avoids scatology for scatology's sake; every gross gag is in service of the story or satire. His figures are grotesque, funny and distorted, but his work doesn't rest on grossing out the reader.

Kat Kon: Kon tends to work really big--like just four panels per huge page. That's because she likes to blow up faces and really zero in their weirder qualities. In issue #2, she works a bit smaller, but still with that thick line that emphasizes character expression and lots of spotting blacks. Issue #3 has one image where a woman has a shirt that says "I refuse to smile for no reason" and loads of dead bodies around her; it's a darkly amusing take on a persistent feminist issue that pervades any number of culture. The fifth issue reinforces this with her take on being a barista and the kinds of comments she gets. Kon isn't much one for metacommentary, letting her figures and images speak for themselves. The format certainly flatters her art and adds greatly to its punch.

Alex Potts: His comics took time to really grow on me, as he tends to use a 5 x 7 grid in each issue. That grid minimizes his art while pushing the reader through quickly, but his low-key narratives regarding the character Philip have a surprisingly dark tone to them. Potts reminds me a bit of Chris Ware in the way he uses small panels to his advantage and lets the reader figure out the implications of the character's story for themselves.

Steve Tillotson: Of all the artists in the Reader, Tillotson is the one who took the greatest advantage of the formal possibilities of working big. His trademark is using a grid that simultaneously depicts a single image and that breaks it up to allow individual actions by the characters. His rendering is superb, as he draws both cute & simple characters as well as lush backgrounds. I'm not sure I'd be up to seeing a book's worth of his strips, but that's what makes him perfect for an anthology.

Ellen Lindner: A long-time favorite of mine, Lindner uses her Reader space for autobio (which has always been funny and sharply observed) and splashes it with huge swaths of vivid color. Oranges, yellows, greens, pinks and purples all tend to dominate her comics here, grabbing the reader's eye while she relates witty and thoughtful anecdotes.

Sina Shamsavari: His autobio centers around relationships and loneliness as a gay man in London. His line varies from a bold, naturalistic style to a more fragile, angular look that incorporates splashes of color. I love the way he varies approaches from issue to issue. In some, he does a single narrative and in others, four 2 x 3 panel mini-narratives. All of them focus on the pros and cons of being alone, of being an outsider even in gay culture. The comics are philosophical and thoughtful rather than whiny, but one can still feel Shamsavari's(variously also known as Sina Evil and Sina Sparrow) the depths of his sadness. That's mitigated by the ways in which he finds to express himself. The sophistication of his autobio is a perfect balance for the sillier stuff in the Reader.

Paul O'Connell: O'Connell's biography of model and singer Sabrina in #1 was a strong piece, using photo-reference to create a narrative while giving it a "pop art" effect through the nonintuitive application of color. Less successful was a "clowns in hell" experiment with Addy Evenson; this page was dissonant to the point of incoherency.

Julia Homersham: Homersham appeared in the first two issues with a number of goofy gags that riff on inanimate objects like food or animals behaving as humans. The first issue features single-panel gags, while the second issue is all strips of various lengths. Homersham is heavy on both verbal and visual puns, and there are some groaners in there. In the context of the reader, her work acts as a nice palate cleanser for heavier work. Her "History of English Puddings" page is not strictly comics, but the nomenclature and explanation of many of these bizarre dishes is both bewildering and amusing.

Tobias Tak: Tak is a great draftsman who pulls out all the stops with his use of color. The actual content of his comics is usually self-consciously twee, which makes reading them a slog. They're like reading a Richard Sala comic without any of the bite or the brains and tend to act as a roadblock while reading the anthology. It's labored whimsy.

Gareth Brookes: His page about birds singing to humanity about its arrogance was one of the most overtly-precious, tedious and annoying lectures I've ever seen in comics. The birds are nicely-illustrated, but they're only illustrations and lie inert on the page.

Tim & Alex Levin: Their "Jones" gag strips, in issue after issue, are sloppy without any charm. The jokes themselves are easy pop cultural targets, dumb scatological humor, or bits of randomness that don't go anywhere.

Peter Lally: His take-off on the artist Banksy was silly, poorly-drawn and had an obvious punchline. Much better was "Taxi", a fascinating slice-of-life story (drawn white-on-black backgrounds) that reveals a lot about working-class taxi drivers and an older generation in general. The style Lally used was bold and eye-catching, instantly drawing me in.

Bernadette Bentley: Bentley writes, smart, funny and sharply-observed autobio comics. Her strip about being a guard in a museum and desperately trying to find things to do to stave off boredom is clever for her use of strike-outs in her text to couch meanings. The story about her mother trying to use art to draw out mentally handicapped people that was subsequently shot down by superiors was heart-breaking.

Barnath Richards: He did just one page for the Reader, but it's a doozy: a beautifully drawn and colored one-pager about remembering a TV show from his youth about a robot. In just three panels, he captures the vividness of this memory without wallowing too much in the nostalgia of the moment.

Hannah Eaton: Her densely rendered story about her grandfather hauling corpses for a living was funny and evocative of a different and often stranger era.

Jimi Gherkin: Gherkin's comics are mostly silly, but I thought his affectionate tribute to Harvey Pekar and R.Crumb in "The Jimi Gherkin Name Story" was effective both as homage and as a way of exploring his own past.

Elliot Baggott: Baggott is another artist who dove into the opportunity given to him by having such a big page with enormous relish. His first strip, a single illustration that follows a fox down a building and through a city, is a marvel of clear formal cleverness. His silent strip in #3, done in the style of stained glass, is a gag about how movable type transformed the world, complete with a plop take at the end. If his first strip was remarkable for its use of negative space, the second one is fascinating due to how the reader is dropped into a landscape entirely suffused with color. "Boss Talk" in #5 is a more conventional strip that's a takedown of thinly veiled sexism.

Bird: Bird's mediation on why we worship what we worship and the sheer weirdness of being alive in #3 was funny and thoughtful, and his thin line combined with a restrained use of color made it a highlight. Jokes about allergies and "Happy Days" in #4 could have been hacky, but they were so well-constructed that the set-ups were just as amusing as the punchlines; the character construction was completely different than his work in #3 but their rounded, roly-poly quality was entirely appropriate for this sort of joke.

Maartje Schalkx: Schalkx's strips are models of economy and efficiency, as they mostly depict just her head, and remove most of her facial features at that. There's one strip in particular where we see just her head on a pillow and her eyes open, staring at a man sleeping next to her with his eyes closed. She flips back and forth in sequence on a panel-free page, sparking a silent reverie about perhaps why she's there and who she happens to be sleeping next to. Another issue simply featured her head bouncing down the page, while another issue features her head interacting with other heads at an LGBT disco, where she's trying hard to pick someone up. That strip also features soft pastels in the background, adding to the ethereal feel of that particular scenario. Schalkx uses the entire page in smart ways that made seeing her work a pleasure in every issue.

Craig Burston: I'm not generally a fan of 8-bit style drawings, but Burston's "Low-Res Des" strips are funny because they make the formal qualities of the work part of the narrative. The strip about the fly (in an homage to the film The Fly) was especially amusing.

Ralph Kidson: Kidson's first strip was called "Big Balls Crow", which is about all you need to know about it. The rest of his work in the Reader is silly without otherwise being distinctive.

Sean Duffield: I found little to interest me in Duffield's work; when it wasn't mining scatological humor for its own sake, it seemed overly provincial. It was too locked into local, political and popular references to resonate with me, though perhaps that wouldn't be true of someone living in Britain.

Noelle Barby: Her autobio strip about encountering the forces of sexual debauchery (at last!) in high school was hilarious, as were the depictions of her particular sexual misadventures. Seeing Lust narrate her disappointing future sexual adventures in high school was also amusing, though Barby did at least hold out hope for herself for "life after high school".

James Parsons: Parson's first strip that sees football hooligans wearing the red cross on their faces was mostly clever because of the red crosses on the ambulances that arrive after the inevitable dust-up. His strip in #5 about developing a crush on the actress Sarah Douglas, who played the villainous Ursa in Superman II. It's the rare strip that's both intensely personal and dedicated to one's id but also finds ways to ridicule his own obsessions. The drawings themselves are hilarious--especially the cartoony ones of his penis.

Sally-Anne Hickman: Hickman's "SallyShinyStars" comic strip was a highlight of #5, detailing in grotesque and colorful fashion certain anecdotes about working in a market and the sort of customers she encountered. Her self-caricature is especially amusing.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Brit Comics; Sean Azzopardi, Oliver East

Let's take a look at two British cartoonists known for poetic comics abstracted from their daily lives.

The Homesick Truant's Cumbrian Yarn, by Oliver East. Somehow, this is the first comic by East that I've read despite his solid reputation over the past few years. The short description of this autobio comic is that it describes East's walk from Arnside to Grange Over Sands in Northwest England's county of Cumbria. He makes the walk for no other reason than as a thing to do, walking as near the railroad tracks as possible but taking nearly seven hours to make it to his destination because of the mud, sand, wild animals, and odd strangers. There's a strong John Porcellino influence at work here, which isn't surprising, but East's voice is quite different. He has a wonderfully dry and sarcastic wit that accompanies his spare, blotchy line that goes from depicting moments of great stillness to accelerating into frenzied moments of pursuit.

His narrative captions veer between simple and descriptive to saying things like, in discussing the distance he must walk "Somewhere between 200 K and fuck loads" or a brightening day as "The overcast sky like a Tupperware lid. And the tub has just been removed is all. Bright but still locked in." His page layout instructs the reader as to what to pay attention to without actually saying it. When he sticks to a 2 x 3 grid on the page, this signals a steady walking rhythm. When he expands to a 2 x 2 grid on page seven, he wants the reader to slow down and observe the damage done by recent storms, which is marvelously depicted by a blotchy, splattered ink technique. Later on, when he's chased by a dog, he adds more panels to get the reader into the action and fear of the event, reducing both his body and the dog to rudimentary sketches flashing across the page. The comic is full of little delights and surprises such as this, as East drops hints and clues about his own personality without ever discussing why he's making this particular trek. It is simply something that he needs to do, and the degree of difficulty as well as its eventual conclusion are both implicitly tied to a certain emotional feeling of earned triumph, a task completed. East helps the reader see the beauty in the mud, the downed branches, the locks and levees and the simple struggle of putting one foot in front of another--all without calling attention to that beauty in his narrative. It's all in the drawings, whose beautiful immediacy and sketchiness draws the reader in.