Karl Stevens is known for his photorealist comics, using a dense amount of cross-hatching, shading and color to bring his drawings to life. However, his latest (and last) collection of comics from his gig at the Boston Phoenix shows off a wide range of styles and approaches. There's one thing that's consistent in all of them: Stevens is very funny. Indeed, his comic timing has only sharpened as he wandered from standard autobio tropes to reality-bending imagery and events. At heart, Stevens has a real ear for funny anecdotes and how to relate them. Some of them are provoked by his own weirdness or silliness, but others are simple sharply observed and rendered so as to provide the funniest outcome.

For example, in the strip above, it's presumably Stevens who's rambling on about living in a dystopia. The woman in the strip is watching TV (made clear by the light flashing on her face) and barely tolerating his nonsense until she finally tells him to shut up because her show has come back on. The humor in the strip is derived not so much from Stevens' out-of-context and possibly drunken babble, but from the way her eyes move back and forth at Stevens and the way her lips wrinkle up. Stevens employs that realistic style but pays close attention to panel-to-panel transitions and small movements, and that's what gives life to his drawings. That's what sets him apart from other photorealist cartoonists or cartoonists who fully paint their comics: he may be working from poses, but he transforms them into fully active, breathing comic strips.

Stevens seems to have a particularly good time drawing the adventures of his "descendant", Karl VIII, in the year 2312. It's a hilarious lampoon of privileged white frat boy culture, as the bored and dissolute Karl is unimpressed by an array of wonders and miracles. Riding giant bunny rabbits, visiting the mermaid planet and having a tree cat that can teleport him anywhere is dull, especially if anyone he encounters is slow to accommodate him or entertain him. It's also an excuse for Stevens to draw crazy stuff. He's not afraid to deviate from his usual formula from strip to strip, as when he starts to draw a Garfield-style strip like Jim Davis, There are other pages where he features what looks like a quick preliminary sketch as a final product, pages where his figures have far less detail, and other pages featuring realistic drawings of fanciful creatures, like Pope Cat.

Throughout it all, Stevens displays a restlessness that borders on the existential. He isn't interested in providing context or backstories regarding the people who appear in his stories but instead is more interested in capturing singular moments in time. That includes the awkward and funny interactions he has with his nude models, as his attempts to crack jokes or introduce weird topics of conversation with them frequently falls painfully flat. Stevens slips between black & white and color images as though to tell the reader that they're all just pictures, "realistic" as some might seem. That extends to reproducing precisely the same image as a black and white and then as a color painting. The other thing that sets Stevens apart as a cartoonist, as opposed to an illustrator, is that his understanding of gesture and the way bodies relate to each other in time and space is nuanced and sensitive. This all allows him to depict spaces inbetween, the moments between Big Moments in our lives, and the cracks between meaningful events. While the strips are not directly related, they nonetheless gain a sort of forward momentum, detailing a narrative that's not story based or even emotion-based, but rather one based on one man's imagination. It's as though the reader is made privy to Stevens' stream-of-consciousness ideas about what's catching his attention at any given moment, and Stevens captures that snapshot with that mixture of fidelity and strangeness that's a part of all our daydreams.

This is the blog of comics critic Rob Clough. I have writings elsewhere at SOLRAD.co, TCJ.com and a bunch more. I read and review everything sent to me eventually, especially minicomics. My address is: Rob Clough 881 Martin Luther King Junior King Blvd Apt 10 i Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Monday, September 30, 2013

Saturday, September 28, 2013

A Couple of Worthy Fundraisers

I wanted to make mention of a couple of worthy fundraisers. First is funding several months' worth of comics from Yeti Press. This will include a new comic from Kevin Budnik, an artist whose work I enjoy quite a bit. Sam Sharpe, another talented cartoonist, will also have a book. This kickstarter is close to being funded, but I'd still take a look at it.

I also want to heartily endorse the travel/research fundraiser for T.Edward Bak. He's touring in support of volume one of his Wild Man series, Island of Memory. This tour will fund Bak's appearances, including one I'm trying to put together here at Duke.

I also want to heartily endorse the travel/research fundraiser for T.Edward Bak. He's touring in support of volume one of his Wild Man series, Island of Memory. This tour will fund Bak's appearances, including one I'm trying to put together here at Duke.

Friday, September 27, 2013

Chameleon: Jim Rugg and Supermag

Jim Rugg, like many cartoonists whose tastes run toward the edgier and trashier neighborhoods of underground comics and culture, has always had a taste for exploitation films and over-the-top imagery in general. His chief strengths as a cartoonist and illustrator are his ability to draw absolutely anything with an astounding amount of fidelity with regard to whatever he's doing, and to employ a remarkable restraint while doing so. In his remarkably striking catch-all anthology Supermag, published by AdHouse Books. Rugg reveals a restless cartoonist who's all over the map precisely because he can't quite figure out how to limit himself to any one particular style. Rugg sometimes seems like a cartoonist in search of an idea worthy of his talent, worthy of spending years of working on it.

Rugg could easily be a mainstream superhero artist. His line and use of color on strips like "USApe" and "Duke Armstrong: The World's Mightiest Golfer" reveal an artist in total command of the medium, one who has an intuitive sense of how to depict action and creative effective panel-to-panel transitions. At the same time, he can't help but take the piss out of genre comics. USApe is both a paean to 80s-style, jingoistic action films and an over-the-top satire of same. Duke Armstrong's premise (a golfer whose aim is so unerring that he can take down airplanes and beat men to death with his clubs) is so ridiculous that the macho stereotypes and cliches that the strip otherwise embraces with a straight face look absurd. "Bigfoot Fist Fight" is another variation on mashing up genre nostalgia with current alt-comics trends; here, Rugg uses a scratchy and dirty line not unlike a lot of other alt-comics cartoonists who dip their toe into genre waters. His golden age action pastiche, "Captain Kidd: Explorer" is an astounding work of verisimilitude as Rugg channels Milton Caniff and once again plays up macho and sexist cliches while poking fun at them.

Rugg is just as comfortable stretching out using a more traditional alt-comics approach. He channels Dan Clowes (circa Velvet Glove) in the Robin Bougie-written "One Night In Paris", a delightfully sleazy story about a young man winding up with two friends at a legendary adult theater. Rugg captures that flatness of affect, the stooped shoulders and poor posture and the human grotesqueries dead-on here, but it still retains Rugg's signature clarity. That clarity makes him a killer illustrator, as images for Foxing Quarterly (a couple kissing in a library as the reader's view is obstructed by books) and Sleazy Slice (a woman going down on a man in a bathroom stall, with only a side view of the closed stall available) indicate. I enjoyed the juxtaposition of those two images, which suggested a sequential connection despite originally being drawn for separate assignments.

Really, there's a treasure on nearly every page here. Rugg does a Tom and Jerry type strip that has real and permanent repercussions for the mice, and it's both hilarious and horrible. He also does autobio, a Rob Liefeld pastiche that is jaw-dropping and slice of life stories. Rugg clearly loves all of it, all of comics, all of culture, high and low. Rugg seems to delight in fragments and the way they play on a page without outside context. Of course, playing those fragments against each other creates its own, new context, giving Supermag the feel of being constructed from lost copies of other publications full of that sort of image or comics. Still, I can't shake that sense of restlessness as I read this book: strips with middles but no beginnings or endings, glimpses and fragments of intriguing projects, bits and pieces from anthologies. Rugg has already done one pastiche adventure comic (Afrodesiac) and an homage to street culture and action films (Street Angel, with Brian Maruca). I'll be curious to see where his interests take him when he decides to do another long-form comic.

Rugg could easily be a mainstream superhero artist. His line and use of color on strips like "USApe" and "Duke Armstrong: The World's Mightiest Golfer" reveal an artist in total command of the medium, one who has an intuitive sense of how to depict action and creative effective panel-to-panel transitions. At the same time, he can't help but take the piss out of genre comics. USApe is both a paean to 80s-style, jingoistic action films and an over-the-top satire of same. Duke Armstrong's premise (a golfer whose aim is so unerring that he can take down airplanes and beat men to death with his clubs) is so ridiculous that the macho stereotypes and cliches that the strip otherwise embraces with a straight face look absurd. "Bigfoot Fist Fight" is another variation on mashing up genre nostalgia with current alt-comics trends; here, Rugg uses a scratchy and dirty line not unlike a lot of other alt-comics cartoonists who dip their toe into genre waters. His golden age action pastiche, "Captain Kidd: Explorer" is an astounding work of verisimilitude as Rugg channels Milton Caniff and once again plays up macho and sexist cliches while poking fun at them.

Rugg is just as comfortable stretching out using a more traditional alt-comics approach. He channels Dan Clowes (circa Velvet Glove) in the Robin Bougie-written "One Night In Paris", a delightfully sleazy story about a young man winding up with two friends at a legendary adult theater. Rugg captures that flatness of affect, the stooped shoulders and poor posture and the human grotesqueries dead-on here, but it still retains Rugg's signature clarity. That clarity makes him a killer illustrator, as images for Foxing Quarterly (a couple kissing in a library as the reader's view is obstructed by books) and Sleazy Slice (a woman going down on a man in a bathroom stall, with only a side view of the closed stall available) indicate. I enjoyed the juxtaposition of those two images, which suggested a sequential connection despite originally being drawn for separate assignments.

Really, there's a treasure on nearly every page here. Rugg does a Tom and Jerry type strip that has real and permanent repercussions for the mice, and it's both hilarious and horrible. He also does autobio, a Rob Liefeld pastiche that is jaw-dropping and slice of life stories. Rugg clearly loves all of it, all of comics, all of culture, high and low. Rugg seems to delight in fragments and the way they play on a page without outside context. Of course, playing those fragments against each other creates its own, new context, giving Supermag the feel of being constructed from lost copies of other publications full of that sort of image or comics. Still, I can't shake that sense of restlessness as I read this book: strips with middles but no beginnings or endings, glimpses and fragments of intriguing projects, bits and pieces from anthologies. Rugg has already done one pastiche adventure comic (Afrodesiac) and an homage to street culture and action films (Street Angel, with Brian Maruca). I'll be curious to see where his interests take him when he decides to do another long-form comic.

Thursday, September 26, 2013

SPX 2013: A Natural Progression

Some thoughts on the latest iteration of SPX, which happens to be the 13th I've attended since 1997 (skipping 2005, 2007 and 2010 and of course the cancelled 2001 show).

* I think one reason why this year's show was so startling to long-time attendees and exhibitors was that we were suddenly confronted with the future of the show. There are almost no scenarios where the show as presently constructed could get any bigger. For a mid-sized show, there simply aren't any better venues in the DC area. Going to a convention center could bring many additional costs, like using union labor, for example. There aren't going to be 20,000 people coming to SPX any time in the near future. Indeed, now that the show has completely taken over all available event space in the ballroom, there were times when the crowds even felt a bit thin, even if the actual number of people attending was greater than last year. The snafus regarding registration forced the hand of the executive committee so as to avoid a total public relations meltdown that invalidated their first-come, first serve policy by shutting out some of the top cartoonists and small press publishers. It was a bold move to simply solve the problem by adding more tables.

* The big fear on behalf of all exhibitors was spreading the dollars of the attendees too thin by having too many choices. I talked to a number of different cartoonists about this. There were a few trends I noticed:

1. If you had a book on the SPX debut list, you probably made money on it. The same was true for some folks who were guided by the likes of Rob McMonigal, Tom Spurgeon and myself. With more options than ever, people wanted some kind of guide to what was good or new. I can think of a dozen artists who brought between 30-50 copies of their new comic, and many sold out of them on Saturday. Many creators who were on Tony Breed's list of queer cartoonists had plenty of people come look for them.

2. If you were new to SPX, you probably did pretty well. Several newcomers I talked to, especially some who have put out a number of comics over the years, reported solid sales.

3. If you were selling prints, you probably made some money. The crowds were hungry for eye-catching art at affordable prices.

4. If you didn't have a lot of new comics and were a familiar face, you probably didn't move a lot of backstock. While the crowd is slowly expanding, it does tend to be the same kind of people, year after year.

5. Various publishers reported good sales, but nothing approaching the table-clearing of last year.

6. International cartoonists reported mixed sales. NoBrow seemed to do well once again. Italian publisher Delibile had one of the best books of the show in Mother, and they reported that they did pretty well. Philippa Rice sold out of her own comics by Sunday.

7. Having a big-ticket, high-prestige item usually paid off, like Jeff Smith and his collected RASL.

* This may have been the most diverse comics show I've ever attended. SPX finally caught up to more cosmopolitan shows, and the gender breakdown for both attendees and exhibitors is close to 50-50. That was sagely reflected in terms of the programming and special guest selection. (More on that in a bit.) It was more racially diverse than I've seen at any small press show, with the number of African-American attendees and exhibitors, while still small, looking like it was three or four times as great than in any other year. The same was true of Asian creators and attendees. There was probably a greater concentration of queer fans and creators at this show than in any other year. Part of this is a generational thing and an internet thing; the tumblr meetup on Sunday, for example, was dominated by people under 25 years old. The younger crowd also seemed to have extremely catholic tastes, judging by post-show "swag posts". All of these trends speak well of the show and its future, especially as SPX hopes to continue to slowly build its fanbase.

* Every year, I make a spreadsheet of who will be at the show, and I first note the artists I'm familiar with. Then I visit the websites of everyone else to seem if their work would be of interest to me and annotate a map with which I navigate the room. This year, there were a staggering 250-300 artists I wanted to see out of 600-700 exhibiting. This meant that I started Saturday morning at the southeast corner of the room and slowly made my way up. By the end of the day, I had not made it all the way across the room, despite attending no panels and taking only a 15 minute break for lunch. Looking back at the guest list for the 2000 show, there weren't more than 50 artists whose work I was directly interested in. The main sacrifice for me here is taking the time to get sketches. My sole exception was to get a sketch of Lisa Leavenworth from the great Peter Bagge.

* For me, this is very much a working experience. I'm in the room to survey the scene, talk to cartoonists about the show and pick up review copies. There was truly a staggering amount of good material to be found. Of course, the social aspect of the show is another highlight. My wife is an aspiring cartoonist and attended the workshop headed by Josh Bayer and Alec Longstreth. She passed on that Bayer was brimming with incredibly useful drawing tips that made sense and were easy to implement. Longstreth's discipline in getting cartoonists to draw quickly in drills was something she wished she could have in everyday life: "OK, now two minutes for the dishes. Go! Stop! Now 2 minutes on sweeping. Go!"

* For my part, I was happy to see so many comics people and get a chance to chat: Marc Sobel, Tom Spurgeon, Annie Koyama, Simon Moreton, Sean Azzopardi and Jon McNaught (all from England), Dash Shaw, Ed Piskor, Jacq Cohen, Gary Groth, Heidi MacDonald (to whom I recommended Anna Bongiovanni's book Out of Hollow Water), Jen Vaughn, Michael Kupperman. I was warmly greeted by Jesse Reklaw, whom I hadn't seen in quite some time. It was a great pleasure to meet the talented Daryl Seitchik, Julia Gfrorer, Jason Levian, Lizz Lunney, Philippa Rice, Luis Echavarria and so many more. Then there were the hordes of CCS cartoonists, new and old to me. There are so many of them now that they're scattered across the room. I had an interesting conversation with each and every cartoonist I encountered, which is one reason why it took such a long time to get around the room. I made a couple of suggestions for Joe "Jog" McCulloch, who was carrying out his mission collecting comics for the Library of Congress this year. He was trying to collect as many international comics as possible.

* After last year's once-in-a-generation show, SPX was wise not to try to follow that act with a small number of special guests. Instead, they went crazy-big, inviting over a dozen creators from around the world. This show emphasized alt-comics' depth above all else. The committee was also aware of the flack they got last year from having a relative scarcity of special guests who were women. This year, there was no such problem, as Ulli Lust, Lisa Hanawalt, Liza Donnelly, Rutu Modan and many others were special guests. While last year's guest list was an oddity in terms of its guest list (there's usually more balance), the committee was still wise to move as it did.

* Perhaps my favorite moment of the show was when Carol Tyler stopped for a second with my wife and me to show us original pages of the comic strip she does for Cincinnati Magazine. They are staggeringly beautiful and inventive. Carol was one of many veteran cartoonists looking for a way to make a real living from their comics. This was a theme for many folks I talked to who were over thirty and/or had published through the likes of Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly. While there's still a certain amount of prestige to be gained in working with them. there's still not much money.

* I've noted in recent years that it's possible for entirely different kinds of comics fans to have totally different experiences of the show. There was even a bit of tension among the tribes last year when a number of prominent webcomics creators were chosen to present the Ignatz awards, baffling (and annoying) cartoonists from the art-comics side of the spectrum. Increasing the size of the room seemed to dissipate that tension a bit; Topatoco was nestled in the back of the room, and the tables seemed to work themselves out nicely in terms of what cartoonists were paired with others.

* I imagine some artists who got an SPX table hoping to cash in on last year's sales were disappointed. I am pretty certain that the success of last year's show led to "Tablegeddon", and I'm guessing that this will work itself out next year for those cartoonists who lost a lot of money and didn't find the social interactions worth their time as a form of compensation. While the committee will take a look at the feedback they receive from cartoonists, I'm guessing that the new room is here to stay.

* Liza Donnelly hosted the Ignatz Awards, which as usual crammed a couple of hundred people into the room. There were more women nominated for awards than ever before, including all five Outstanding Graphic Novel nominees. Apropos of this, Donnelly selected women to present each award, a group that included Jen Vaughn, Carol Tyler, Rutu Modan, Kate Leth, Raina Telgemeier, Becky (& Frank), Ulli Lust, Mikhaela Reed, and Lucy Knisley. This was easily my favorite Ignatz awards ceremony ever. It had its usual brisk pace, and each present was quite funny. After Ulli Lust won for Outstanding Graphic Novel, Rutu Modan (who had just lost) was up to present the final award and cracked wise about it. "Perhaps you should look into this for the future", she said. Lust was stunned that in a short period of time, her work was finally translated into english, was nominated for an award and then got the award. She also joined in with the show's presenters in paying tribute to Kim Thompson; his amiable presence was missed at this show. Chip Mosher of Comixology had the last word and was quite aware that "I'm the guy keeping you from the chocolate fountain and booze". Mosher is a long-time fan in addition to being an exec at Comixology, and he told everyone in the room to avail themselves of their service. I saw him interacting with Simon Moreton and Warren Craghead, whose comics-as-poetry are about as far away from mainstream as you can get, and he said that they could definitely find an audience there. It's a very intriguing idea to say the least. Then Mosher produced an armful of drink tickets and said "Come find me to get them!"

* Michael DeForge humbly accepted three bricks (for Outstanding Series, Collection and the coveted Outstanding Artist). He joined the exclusive career Four Brick Club, a distinction shared only by five other cartoonists: Chris Ware (6), Dan Clowes (6), Jaime Hernandez (5), Kevin Huizenga (5) and James Kochalka (4). Jillian Tamaki and Chuck Forsman joined the Three Brick Club, also occupied by Anders Nilsen, Carla Speed McNeil and Eddie Campbell. (Twenty-two other cartoonists have won two Ignatz Awards).

* My panel was titled "Queering the Maisntream?", and it featured Rob Kirby, L. Nichols, Charles "Zan" Christensen, Dylan Edwards and Laurel Lynn Leake. Kirby and I carefully assembled the panel to reflect as wide and diverse a range as possible of age, gender, gender identity, subject matter, publishing experience, and editorial experience. The energy in the room was palpable as there was standing room only. This was easily my best experience moderating a panel, as each and every one of the panelists was thoughtful, passionate and articulate. The idea behind the panel was to examine the ways in which queer culture was crossing over into mainstream culture in the comics world and why. Edwards' discussion of trans issues was on point, noting that while he originally intended his book Transposes for a gay male audience (for the purpose of education, essentially), he's been surprised and pleased to see it embraced by straight audiences as well. Christensen talked about his company Northwest Press being open to publishing all kinds of stories and not specifically naming it to reflect only queer issues, though obviously that is a focus. He talked about the recent anthology Anything That Loves, which is about the experience of bisexuals and others whose identity can't be captured by a simple gay/straight binary, as an example of breaking out of the parallel world that gay comics has occupied for forty years. Many noted that a big positive, recent trend was the way that uncompromising queer content is increasingly embraced by straight audiences, like Justin Hall's anthology No Straight Lines and Gengoroh Tagame.

Leake was there to give the perspective of a young cartoonist, but I was also interested in her experiences at the Center for Cartoon Studies. Her identity as a queer person has never been an issue, either with her classmates (many of whom are queer-identified) or her teachers. She also noted that one reason why the barriers between gay and straight culture are breaking down is because even if a straight person doesn't actually know a gay person, they are probably fans of gay celebrities -- and in our internet culture, celebrities are sort of our friends. When asked if this was a permanent trend or just a temporary blip, they all leaned toward the former, because of the internet creating connections, providing information and generally giving an outlet and a voice. Nichols noted that while her comics have rarely explicitly touched on being queer (with the exception of her new series Flocks), she never felt any resistance in the alt-comics community. She also touched on breaking barriers between those of faith and queer culture, just as Leake touched on breaking down binary definitions related to sex, gender and sexuality. Kirby spoke of reaching out to alt-comics culture many years ago when he asked John Porcellino to distribute his comics through his network, a request Porcellino happily agreed to. Kirby's Tablegeddon anthology minicomic included a fine list of queer and straight cartoonists all discussing their experiences tabling at comics shows. Kirby didn't make a big deal out of this rare pairing of cartoonists, nor did he have to. Sometimes sexual identity was an issue in the stories here, and sometimes it wasn't, but the entire book was appealing to queer or straight audiences. I ran out of time before I ran out of questions. Hopefully, the SPX web site will have this streaming soon.

* I have three bags' worth of comics to sort through, but some interesting books included the new Monster anthology, the aforementioned Mother anthology, the Queerotica anthology published by some CCS students and grads, and the beautiful Dog City anthology, also published by CCS students.The latter is a box containing several minicomics, a short anthology, a magazine, a poster, patches and little drawings. What's great about it is not just that it's a design marvel, but that the material within is extremely strong.

* Circling back around, the one concern I have about this show and alt-comics in general is that the supply seems to be far greater than demand. There are more good young cartoonists now than ever. Sam Alden, a worthy winner of Promising New Talent, is exploding into a huge talent right now, thanks to his tremendous work ethic. His humility and talent remind me a lot of Michael DeForge, Dash Shaw and Luke Pearson: quiet guys who simply work all of the time, sloughing off old work like dead skin. But will Alden have a big enough audience to focus entirely on comics without taking another job or living in relative poverty? The young presence at this show gives one hope; on Sunday, both ATMs in the hall had been cleared of a total of $40,000. Many artists also had Squares as a way of accepting money; this is frankly going to be a requirement at all future shows. More cartoonists are allying themselves with micropublishers who pick up costs, promotion and other production-related tasks that can interfere with cartooning. A new revenue stream is that of the comic shop publishing comics; Kilgore Books publishes both Noah Van Sciver and Joseph Remnant, while Box Brown's Retrofit is being published by Big Planet Comics. These are all positive steps, as are the increasing number of small, regional comics shows. The increasing influence of Tumblr culture is another positive, drawing in readers who don't necessarily read webcomics per se. Comixlogy may hold some answers, but I suspect it will just be another small revenue stream.There's no single solution to this problem; instead, a dozen or more small initiatives need to continue to be spawned to keep afloat the passion of comics.

* I think one reason why this year's show was so startling to long-time attendees and exhibitors was that we were suddenly confronted with the future of the show. There are almost no scenarios where the show as presently constructed could get any bigger. For a mid-sized show, there simply aren't any better venues in the DC area. Going to a convention center could bring many additional costs, like using union labor, for example. There aren't going to be 20,000 people coming to SPX any time in the near future. Indeed, now that the show has completely taken over all available event space in the ballroom, there were times when the crowds even felt a bit thin, even if the actual number of people attending was greater than last year. The snafus regarding registration forced the hand of the executive committee so as to avoid a total public relations meltdown that invalidated their first-come, first serve policy by shutting out some of the top cartoonists and small press publishers. It was a bold move to simply solve the problem by adding more tables.

* The big fear on behalf of all exhibitors was spreading the dollars of the attendees too thin by having too many choices. I talked to a number of different cartoonists about this. There were a few trends I noticed:

1. If you had a book on the SPX debut list, you probably made money on it. The same was true for some folks who were guided by the likes of Rob McMonigal, Tom Spurgeon and myself. With more options than ever, people wanted some kind of guide to what was good or new. I can think of a dozen artists who brought between 30-50 copies of their new comic, and many sold out of them on Saturday. Many creators who were on Tony Breed's list of queer cartoonists had plenty of people come look for them.

2. If you were new to SPX, you probably did pretty well. Several newcomers I talked to, especially some who have put out a number of comics over the years, reported solid sales.

3. If you were selling prints, you probably made some money. The crowds were hungry for eye-catching art at affordable prices.

4. If you didn't have a lot of new comics and were a familiar face, you probably didn't move a lot of backstock. While the crowd is slowly expanding, it does tend to be the same kind of people, year after year.

5. Various publishers reported good sales, but nothing approaching the table-clearing of last year.

6. International cartoonists reported mixed sales. NoBrow seemed to do well once again. Italian publisher Delibile had one of the best books of the show in Mother, and they reported that they did pretty well. Philippa Rice sold out of her own comics by Sunday.

7. Having a big-ticket, high-prestige item usually paid off, like Jeff Smith and his collected RASL.

* This may have been the most diverse comics show I've ever attended. SPX finally caught up to more cosmopolitan shows, and the gender breakdown for both attendees and exhibitors is close to 50-50. That was sagely reflected in terms of the programming and special guest selection. (More on that in a bit.) It was more racially diverse than I've seen at any small press show, with the number of African-American attendees and exhibitors, while still small, looking like it was three or four times as great than in any other year. The same was true of Asian creators and attendees. There was probably a greater concentration of queer fans and creators at this show than in any other year. Part of this is a generational thing and an internet thing; the tumblr meetup on Sunday, for example, was dominated by people under 25 years old. The younger crowd also seemed to have extremely catholic tastes, judging by post-show "swag posts". All of these trends speak well of the show and its future, especially as SPX hopes to continue to slowly build its fanbase.

* Every year, I make a spreadsheet of who will be at the show, and I first note the artists I'm familiar with. Then I visit the websites of everyone else to seem if their work would be of interest to me and annotate a map with which I navigate the room. This year, there were a staggering 250-300 artists I wanted to see out of 600-700 exhibiting. This meant that I started Saturday morning at the southeast corner of the room and slowly made my way up. By the end of the day, I had not made it all the way across the room, despite attending no panels and taking only a 15 minute break for lunch. Looking back at the guest list for the 2000 show, there weren't more than 50 artists whose work I was directly interested in. The main sacrifice for me here is taking the time to get sketches. My sole exception was to get a sketch of Lisa Leavenworth from the great Peter Bagge.

* For me, this is very much a working experience. I'm in the room to survey the scene, talk to cartoonists about the show and pick up review copies. There was truly a staggering amount of good material to be found. Of course, the social aspect of the show is another highlight. My wife is an aspiring cartoonist and attended the workshop headed by Josh Bayer and Alec Longstreth. She passed on that Bayer was brimming with incredibly useful drawing tips that made sense and were easy to implement. Longstreth's discipline in getting cartoonists to draw quickly in drills was something she wished she could have in everyday life: "OK, now two minutes for the dishes. Go! Stop! Now 2 minutes on sweeping. Go!"

* For my part, I was happy to see so many comics people and get a chance to chat: Marc Sobel, Tom Spurgeon, Annie Koyama, Simon Moreton, Sean Azzopardi and Jon McNaught (all from England), Dash Shaw, Ed Piskor, Jacq Cohen, Gary Groth, Heidi MacDonald (to whom I recommended Anna Bongiovanni's book Out of Hollow Water), Jen Vaughn, Michael Kupperman. I was warmly greeted by Jesse Reklaw, whom I hadn't seen in quite some time. It was a great pleasure to meet the talented Daryl Seitchik, Julia Gfrorer, Jason Levian, Lizz Lunney, Philippa Rice, Luis Echavarria and so many more. Then there were the hordes of CCS cartoonists, new and old to me. There are so many of them now that they're scattered across the room. I had an interesting conversation with each and every cartoonist I encountered, which is one reason why it took such a long time to get around the room. I made a couple of suggestions for Joe "Jog" McCulloch, who was carrying out his mission collecting comics for the Library of Congress this year. He was trying to collect as many international comics as possible.

* After last year's once-in-a-generation show, SPX was wise not to try to follow that act with a small number of special guests. Instead, they went crazy-big, inviting over a dozen creators from around the world. This show emphasized alt-comics' depth above all else. The committee was also aware of the flack they got last year from having a relative scarcity of special guests who were women. This year, there was no such problem, as Ulli Lust, Lisa Hanawalt, Liza Donnelly, Rutu Modan and many others were special guests. While last year's guest list was an oddity in terms of its guest list (there's usually more balance), the committee was still wise to move as it did.

* Perhaps my favorite moment of the show was when Carol Tyler stopped for a second with my wife and me to show us original pages of the comic strip she does for Cincinnati Magazine. They are staggeringly beautiful and inventive. Carol was one of many veteran cartoonists looking for a way to make a real living from their comics. This was a theme for many folks I talked to who were over thirty and/or had published through the likes of Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly. While there's still a certain amount of prestige to be gained in working with them. there's still not much money.

* I've noted in recent years that it's possible for entirely different kinds of comics fans to have totally different experiences of the show. There was even a bit of tension among the tribes last year when a number of prominent webcomics creators were chosen to present the Ignatz awards, baffling (and annoying) cartoonists from the art-comics side of the spectrum. Increasing the size of the room seemed to dissipate that tension a bit; Topatoco was nestled in the back of the room, and the tables seemed to work themselves out nicely in terms of what cartoonists were paired with others.

* I imagine some artists who got an SPX table hoping to cash in on last year's sales were disappointed. I am pretty certain that the success of last year's show led to "Tablegeddon", and I'm guessing that this will work itself out next year for those cartoonists who lost a lot of money and didn't find the social interactions worth their time as a form of compensation. While the committee will take a look at the feedback they receive from cartoonists, I'm guessing that the new room is here to stay.

* Liza Donnelly hosted the Ignatz Awards, which as usual crammed a couple of hundred people into the room. There were more women nominated for awards than ever before, including all five Outstanding Graphic Novel nominees. Apropos of this, Donnelly selected women to present each award, a group that included Jen Vaughn, Carol Tyler, Rutu Modan, Kate Leth, Raina Telgemeier, Becky (& Frank), Ulli Lust, Mikhaela Reed, and Lucy Knisley. This was easily my favorite Ignatz awards ceremony ever. It had its usual brisk pace, and each present was quite funny. After Ulli Lust won for Outstanding Graphic Novel, Rutu Modan (who had just lost) was up to present the final award and cracked wise about it. "Perhaps you should look into this for the future", she said. Lust was stunned that in a short period of time, her work was finally translated into english, was nominated for an award and then got the award. She also joined in with the show's presenters in paying tribute to Kim Thompson; his amiable presence was missed at this show. Chip Mosher of Comixology had the last word and was quite aware that "I'm the guy keeping you from the chocolate fountain and booze". Mosher is a long-time fan in addition to being an exec at Comixology, and he told everyone in the room to avail themselves of their service. I saw him interacting with Simon Moreton and Warren Craghead, whose comics-as-poetry are about as far away from mainstream as you can get, and he said that they could definitely find an audience there. It's a very intriguing idea to say the least. Then Mosher produced an armful of drink tickets and said "Come find me to get them!"

* Michael DeForge humbly accepted three bricks (for Outstanding Series, Collection and the coveted Outstanding Artist). He joined the exclusive career Four Brick Club, a distinction shared only by five other cartoonists: Chris Ware (6), Dan Clowes (6), Jaime Hernandez (5), Kevin Huizenga (5) and James Kochalka (4). Jillian Tamaki and Chuck Forsman joined the Three Brick Club, also occupied by Anders Nilsen, Carla Speed McNeil and Eddie Campbell. (Twenty-two other cartoonists have won two Ignatz Awards).

* My panel was titled "Queering the Maisntream?", and it featured Rob Kirby, L. Nichols, Charles "Zan" Christensen, Dylan Edwards and Laurel Lynn Leake. Kirby and I carefully assembled the panel to reflect as wide and diverse a range as possible of age, gender, gender identity, subject matter, publishing experience, and editorial experience. The energy in the room was palpable as there was standing room only. This was easily my best experience moderating a panel, as each and every one of the panelists was thoughtful, passionate and articulate. The idea behind the panel was to examine the ways in which queer culture was crossing over into mainstream culture in the comics world and why. Edwards' discussion of trans issues was on point, noting that while he originally intended his book Transposes for a gay male audience (for the purpose of education, essentially), he's been surprised and pleased to see it embraced by straight audiences as well. Christensen talked about his company Northwest Press being open to publishing all kinds of stories and not specifically naming it to reflect only queer issues, though obviously that is a focus. He talked about the recent anthology Anything That Loves, which is about the experience of bisexuals and others whose identity can't be captured by a simple gay/straight binary, as an example of breaking out of the parallel world that gay comics has occupied for forty years. Many noted that a big positive, recent trend was the way that uncompromising queer content is increasingly embraced by straight audiences, like Justin Hall's anthology No Straight Lines and Gengoroh Tagame.

Leake was there to give the perspective of a young cartoonist, but I was also interested in her experiences at the Center for Cartoon Studies. Her identity as a queer person has never been an issue, either with her classmates (many of whom are queer-identified) or her teachers. She also noted that one reason why the barriers between gay and straight culture are breaking down is because even if a straight person doesn't actually know a gay person, they are probably fans of gay celebrities -- and in our internet culture, celebrities are sort of our friends. When asked if this was a permanent trend or just a temporary blip, they all leaned toward the former, because of the internet creating connections, providing information and generally giving an outlet and a voice. Nichols noted that while her comics have rarely explicitly touched on being queer (with the exception of her new series Flocks), she never felt any resistance in the alt-comics community. She also touched on breaking barriers between those of faith and queer culture, just as Leake touched on breaking down binary definitions related to sex, gender and sexuality. Kirby spoke of reaching out to alt-comics culture many years ago when he asked John Porcellino to distribute his comics through his network, a request Porcellino happily agreed to. Kirby's Tablegeddon anthology minicomic included a fine list of queer and straight cartoonists all discussing their experiences tabling at comics shows. Kirby didn't make a big deal out of this rare pairing of cartoonists, nor did he have to. Sometimes sexual identity was an issue in the stories here, and sometimes it wasn't, but the entire book was appealing to queer or straight audiences. I ran out of time before I ran out of questions. Hopefully, the SPX web site will have this streaming soon.

* I have three bags' worth of comics to sort through, but some interesting books included the new Monster anthology, the aforementioned Mother anthology, the Queerotica anthology published by some CCS students and grads, and the beautiful Dog City anthology, also published by CCS students.The latter is a box containing several minicomics, a short anthology, a magazine, a poster, patches and little drawings. What's great about it is not just that it's a design marvel, but that the material within is extremely strong.

* Circling back around, the one concern I have about this show and alt-comics in general is that the supply seems to be far greater than demand. There are more good young cartoonists now than ever. Sam Alden, a worthy winner of Promising New Talent, is exploding into a huge talent right now, thanks to his tremendous work ethic. His humility and talent remind me a lot of Michael DeForge, Dash Shaw and Luke Pearson: quiet guys who simply work all of the time, sloughing off old work like dead skin. But will Alden have a big enough audience to focus entirely on comics without taking another job or living in relative poverty? The young presence at this show gives one hope; on Sunday, both ATMs in the hall had been cleared of a total of $40,000. Many artists also had Squares as a way of accepting money; this is frankly going to be a requirement at all future shows. More cartoonists are allying themselves with micropublishers who pick up costs, promotion and other production-related tasks that can interfere with cartooning. A new revenue stream is that of the comic shop publishing comics; Kilgore Books publishes both Noah Van Sciver and Joseph Remnant, while Box Brown's Retrofit is being published by Big Planet Comics. These are all positive steps, as are the increasing number of small, regional comics shows. The increasing influence of Tumblr culture is another positive, drawing in readers who don't necessarily read webcomics per se. Comixlogy may hold some answers, but I suspect it will just be another small revenue stream.There's no single solution to this problem; instead, a dozen or more small initiatives need to continue to be spawned to keep afloat the passion of comics.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Minicomics Round-Up: Roberts, Sharpe, R.Smith, Fleener, McMahan

There's no through-line in the minis reviewed in this column this time around, other than I found them all to be quite good.

Powdered Milk #11, by Keiler Roberts. This mini is an especially sharp and subtle bit of storytelling. Roberts has been doing comics about being an artist and a mother for a few years now and hasn't flinched in detailing her struggles with post-partum depression along with the ups and downs of being a parent. This issue is a tightly-drawn series of rapid-fire comments from her toddler daughter, and while many of the comments are hilarious and played for laughs, it's clear that Roberts is drawing these comics as a way of letting off steam as well. Having your child yell at you, hit you, bite you and just do inexplicably destructive things is maddening Children are also quite intuitive and can pick up on emotional signals both subtle and not so subtle, and they are quite willing to confront you on them, like when Roberts' daughter asked why her eyes are crying. Roberts also hints at the difficulties of being a primary caregiver, especially when one is trying to be an artist. There's a page where Roberts tells her daughter "You're supposed to be napping" when she's drawing a strip, only to meet with curiosity from her daughter. When she sees the strip is about her, she says "Thank you for drawing that, Mommy". It's the situation in a nutshell: guilt, joy, frustration, astonishment. In strip after strip, Roberts gets across what it's really like to be a parent.

Viewotron #2, by Sam Sharpe. Employing frequently deadpan anthropomorphic animals as a storytelling device not unlike the artist Jason, this is a devastating story about the disintegration of the relationship between a son and his schizophrenic mother that seems to be at least partly autobiographical. Sharpe opens the comic depicting himself as a child, talking about his mother being missing with a friend, as well as the odd fact that his father let him read the strange, convoluted and paranoid letters she sent to her boy. From there, we see the hopeful reconnection between mother and son as we're privy to Sharpe's nervousness and uncertainty about what, exactly, he wanted from the relationship. Sharpe slowly, painfully details the way his mother's mind starts its descent back into paranoid delusions, as she thinks that her son is part of the "Sharpe crime family" and wants him to disassociate from his father and family completely. He humors her and tries to change the subject as much as possible, helping her when a friend of hers from therapy suddenly commits suicide. The end of the comic is chilling, as Sharpe is forced to confront his mother's mental illness with her when she demands to know if he's seen the horrible things she hallucinated at his house. Even then, the connection he wants to have with her (as opposed to the actual connection) is so strong that he patiently tells her that they just see things differently and that she has a mental illness. At that point, she starts laughing hysterically, writing him off as a duplicate and telling him that her son is dead. Even drawing his characters as anthropomorphic dogs does little to blunt the emotional impact of the scene, and one senses that drawing his characters in this way was as much for Sharpe's benefit as it was for the readers. Sharpe uses a 2x3 panel grid to maintain the same sense of rhythm and pace no matter what the situation, so even the rougher scenes aren't lingered on for very long by either artist or reader. This is a powerful comic that's told with confidence, skill and even flair.

I Am Fire, by Rachael Smith. This is a full-color mini about a couple of wildly dysfunctional teens who develop a crush on each other. British artist Smith has a nicely-honed sense of comic timing and manages to create a pair of protagonists who are near-sociopaths yet strangely likable at the same time. The story follows a girl named Jenny, who creates havoc doing an internship of sorts in a department store, and Chris, a pyromaniac who somehow winds up as an intern for a fire-prevention outfit. While the cover certainly has an apocalyptic feel to it, the actual circumstances of how Chris winds up wearing that sign are quite amusing. Smith is unrelenting in these forty pages when it comes to the obnoxiousness of her characters and the shtick that surrounds them, as the cast includes an obsessed fire safety officer, an alpha male fireman, a dotty saleslady and various other somewhat one-dimensional character types. Smith manages to insert a bit of humanity into the proceedings in a way that doesn't seem ham-fisted, unearned or sentimental, and that rescues the comic from falling into cliche'. Indeed, it provides some rather amusing surprises for a number of characters. Smith's bug-eyed characters remind me a bit of a slicker Kate Beaton or perhaps Raina Telgemeier. That smooth, slick line actually goes nicely with her acerbic sense of humor. Given the way she writes her characters, I thought her use of color was a bit over-the-top, however. Nearly every page had dense, rich colors that at times overpowered the eye, especially on pages where nothing much was actually happening. A more muted palette would have been appropriate for much of the book and might have allowed the reader a better chance to take in the loveliness of her drawing style. There's no question that Smith is funny and talented but a smidgen of restraint could have made this comic even funnier.

You Were Swell, by Sophie McMahan. Getting this comic in the mail is one of those rare occasions when you get a comic that's completely bonkers and fantastic from an artist you've never heard of. This is an amazing series of strips mashing together 50s advertising art and romance comics tropes with modern body horror/body dysmorphia that together give a scathing, hilarious critique of gender norms and roles. "Other Self" illustrates a seemingly happy, white 1950s family with heads that split off, as the narrative caption posits the question "Do you ever feel split between two selves?" It's an arrow aimed right at societal and consensus constructions of "normal" and acts both as a declaration by the artist and a hand extended to the reader. In "What If?", McMahan takes an idyllic scene of three women enjoying ice cream, inserts a traditionally handsome male making a crude remark, and then has the women disintegrate him with a laser eye blast. I found this comic to be hilarious, partly because the wish fulfillment is so obvious but mostly because of the way she juxtaposes bland figures with crazy action. "Winner", which details a beauty queen winning first prize, goes in a similar direction, as she loses all of her teeth upon getting the crown, though no one seems to notice. It's a funny image to begin with, but it also pokes fun at the ways in which beauty is so obviously a socially constructed concept, something the pageant setting makes quite clear.

"Bad Thoughts" is the central piece of the comic, where McMahan explores and admits that the hateful thoughts she has about others are literally ugly and a reflection of her own self-hatred. This comic is a way of acknowledging this tendency and destroying the notion that we are abnormal if we have negative feelings. McMahan subverts and undermines this notion at every turn, like in one strip where a handsome guy tells a beautiful girl with lovely lashes that mascara is made out of bat feces, or another "perfect date" where the couple's faces melt at the end. This remarkable comic covers a lot of ground and hammers home a lot of provocative ideas thanks to McMahan's command over her line and willingness to explore the grotesque. That facade of beauty that she punctures again and again is set up perfectly, as McMahan has an unerring grip both on what makes such art and imagery appealing as well as how it is also innately revolting. That sense of revulsion is almost palpable throughout the comic, whose commentary is less overtly political (though there is a political and satirical element to it) and much more deeply personal. McMahan has an interesting career ahead of her.

The Less You Know, The Better You Feel #2, by Mary Fleener. This early alt-comics era standout continues to draw political comics for The Coast News, focusing in on local government greed and calling them out for getting in bed with big developers trying to extract every dollar possible from her idyllic and arts-oriented beach town in California. Fleener's at her best when she gets into particulars, like in the above strip about the right of every citizen to speak for three minutes at every city council meeting. Another strip gives advice on how to be effective when given that platform. Fleener also veers away from politics to offer amusingly-illustrated recipes, complain about aggressive bikers (those strips are especially hilarious), talk about the local flora and fauna or whatever strikes her fancy. Still learning on the job as a political cartoonist, she's making much better use of simple and striking images and cutting back on fussy over-labeling and complicated drawings. Strips where she compares a local politician named Stocks to MacBeth (complete with the three witches and their cauldron) are a good example of this powerful image-making. Fleener is a naturally funny cartoonist, and it's been interesting to see how she's allowed her whimsical nature to merge with her sharp, focused political instincts to provide cartoons that are memorable and brutal. She's not afraid to repeatedly get out the long knives to carve up hypocrites and greedy politicians who would prefer that the public simply ignore what they're doing.

Powdered Milk #11, by Keiler Roberts. This mini is an especially sharp and subtle bit of storytelling. Roberts has been doing comics about being an artist and a mother for a few years now and hasn't flinched in detailing her struggles with post-partum depression along with the ups and downs of being a parent. This issue is a tightly-drawn series of rapid-fire comments from her toddler daughter, and while many of the comments are hilarious and played for laughs, it's clear that Roberts is drawing these comics as a way of letting off steam as well. Having your child yell at you, hit you, bite you and just do inexplicably destructive things is maddening Children are also quite intuitive and can pick up on emotional signals both subtle and not so subtle, and they are quite willing to confront you on them, like when Roberts' daughter asked why her eyes are crying. Roberts also hints at the difficulties of being a primary caregiver, especially when one is trying to be an artist. There's a page where Roberts tells her daughter "You're supposed to be napping" when she's drawing a strip, only to meet with curiosity from her daughter. When she sees the strip is about her, she says "Thank you for drawing that, Mommy". It's the situation in a nutshell: guilt, joy, frustration, astonishment. In strip after strip, Roberts gets across what it's really like to be a parent.

Viewotron #2, by Sam Sharpe. Employing frequently deadpan anthropomorphic animals as a storytelling device not unlike the artist Jason, this is a devastating story about the disintegration of the relationship between a son and his schizophrenic mother that seems to be at least partly autobiographical. Sharpe opens the comic depicting himself as a child, talking about his mother being missing with a friend, as well as the odd fact that his father let him read the strange, convoluted and paranoid letters she sent to her boy. From there, we see the hopeful reconnection between mother and son as we're privy to Sharpe's nervousness and uncertainty about what, exactly, he wanted from the relationship. Sharpe slowly, painfully details the way his mother's mind starts its descent back into paranoid delusions, as she thinks that her son is part of the "Sharpe crime family" and wants him to disassociate from his father and family completely. He humors her and tries to change the subject as much as possible, helping her when a friend of hers from therapy suddenly commits suicide. The end of the comic is chilling, as Sharpe is forced to confront his mother's mental illness with her when she demands to know if he's seen the horrible things she hallucinated at his house. Even then, the connection he wants to have with her (as opposed to the actual connection) is so strong that he patiently tells her that they just see things differently and that she has a mental illness. At that point, she starts laughing hysterically, writing him off as a duplicate and telling him that her son is dead. Even drawing his characters as anthropomorphic dogs does little to blunt the emotional impact of the scene, and one senses that drawing his characters in this way was as much for Sharpe's benefit as it was for the readers. Sharpe uses a 2x3 panel grid to maintain the same sense of rhythm and pace no matter what the situation, so even the rougher scenes aren't lingered on for very long by either artist or reader. This is a powerful comic that's told with confidence, skill and even flair.

I Am Fire, by Rachael Smith. This is a full-color mini about a couple of wildly dysfunctional teens who develop a crush on each other. British artist Smith has a nicely-honed sense of comic timing and manages to create a pair of protagonists who are near-sociopaths yet strangely likable at the same time. The story follows a girl named Jenny, who creates havoc doing an internship of sorts in a department store, and Chris, a pyromaniac who somehow winds up as an intern for a fire-prevention outfit. While the cover certainly has an apocalyptic feel to it, the actual circumstances of how Chris winds up wearing that sign are quite amusing. Smith is unrelenting in these forty pages when it comes to the obnoxiousness of her characters and the shtick that surrounds them, as the cast includes an obsessed fire safety officer, an alpha male fireman, a dotty saleslady and various other somewhat one-dimensional character types. Smith manages to insert a bit of humanity into the proceedings in a way that doesn't seem ham-fisted, unearned or sentimental, and that rescues the comic from falling into cliche'. Indeed, it provides some rather amusing surprises for a number of characters. Smith's bug-eyed characters remind me a bit of a slicker Kate Beaton or perhaps Raina Telgemeier. That smooth, slick line actually goes nicely with her acerbic sense of humor. Given the way she writes her characters, I thought her use of color was a bit over-the-top, however. Nearly every page had dense, rich colors that at times overpowered the eye, especially on pages where nothing much was actually happening. A more muted palette would have been appropriate for much of the book and might have allowed the reader a better chance to take in the loveliness of her drawing style. There's no question that Smith is funny and talented but a smidgen of restraint could have made this comic even funnier.

You Were Swell, by Sophie McMahan. Getting this comic in the mail is one of those rare occasions when you get a comic that's completely bonkers and fantastic from an artist you've never heard of. This is an amazing series of strips mashing together 50s advertising art and romance comics tropes with modern body horror/body dysmorphia that together give a scathing, hilarious critique of gender norms and roles. "Other Self" illustrates a seemingly happy, white 1950s family with heads that split off, as the narrative caption posits the question "Do you ever feel split between two selves?" It's an arrow aimed right at societal and consensus constructions of "normal" and acts both as a declaration by the artist and a hand extended to the reader. In "What If?", McMahan takes an idyllic scene of three women enjoying ice cream, inserts a traditionally handsome male making a crude remark, and then has the women disintegrate him with a laser eye blast. I found this comic to be hilarious, partly because the wish fulfillment is so obvious but mostly because of the way she juxtaposes bland figures with crazy action. "Winner", which details a beauty queen winning first prize, goes in a similar direction, as she loses all of her teeth upon getting the crown, though no one seems to notice. It's a funny image to begin with, but it also pokes fun at the ways in which beauty is so obviously a socially constructed concept, something the pageant setting makes quite clear.

"Bad Thoughts" is the central piece of the comic, where McMahan explores and admits that the hateful thoughts she has about others are literally ugly and a reflection of her own self-hatred. This comic is a way of acknowledging this tendency and destroying the notion that we are abnormal if we have negative feelings. McMahan subverts and undermines this notion at every turn, like in one strip where a handsome guy tells a beautiful girl with lovely lashes that mascara is made out of bat feces, or another "perfect date" where the couple's faces melt at the end. This remarkable comic covers a lot of ground and hammers home a lot of provocative ideas thanks to McMahan's command over her line and willingness to explore the grotesque. That facade of beauty that she punctures again and again is set up perfectly, as McMahan has an unerring grip both on what makes such art and imagery appealing as well as how it is also innately revolting. That sense of revulsion is almost palpable throughout the comic, whose commentary is less overtly political (though there is a political and satirical element to it) and much more deeply personal. McMahan has an interesting career ahead of her.

The Less You Know, The Better You Feel #2, by Mary Fleener. This early alt-comics era standout continues to draw political comics for The Coast News, focusing in on local government greed and calling them out for getting in bed with big developers trying to extract every dollar possible from her idyllic and arts-oriented beach town in California. Fleener's at her best when she gets into particulars, like in the above strip about the right of every citizen to speak for three minutes at every city council meeting. Another strip gives advice on how to be effective when given that platform. Fleener also veers away from politics to offer amusingly-illustrated recipes, complain about aggressive bikers (those strips are especially hilarious), talk about the local flora and fauna or whatever strikes her fancy. Still learning on the job as a political cartoonist, she's making much better use of simple and striking images and cutting back on fussy over-labeling and complicated drawings. Strips where she compares a local politician named Stocks to MacBeth (complete with the three witches and their cauldron) are a good example of this powerful image-making. Fleener is a naturally funny cartoonist, and it's been interesting to see how she's allowed her whimsical nature to merge with her sharp, focused political instincts to provide cartoons that are memorable and brutal. She's not afraid to repeatedly get out the long knives to carve up hypocrites and greedy politicians who would prefer that the public simply ignore what they're doing.

Monday, September 23, 2013

More Minis From Cara Bean

Let's take a look at some old and new minis from the cartoonist Cara Bean. Bean's been doing minis on and off for a few years now, but she seems to be really concentrating on comics in particular at the moment. As a result, she's rapidly evolving as a cartoonist.

The Gremlins Movie Incident is autobio that recalls her father taking Bean and her rambunctious siblings and cousins to the movie Gremlins. Though rated PG, its grisly (if cartoonish) violence and generally dark themes made it wildly age-inappropriate for little kids, so much so that it led to the PG-13 rating. This is a funny comic, but it's also about the way the film traumatized everyone who saw it in different ways. Bean thought that gremlins would come up out of the toilet to get her and she needed company in there; her sister was afraid they'd come get her at night. In terms of the art, there are three things I especially liked. First, the way Bean draws figures as looking slightly like sausages (or at times, like beans!) is amusing, especially when she gives them big, bulging eyes. Second, her formatting is all over the map in ways that keep the reader guessing: single panel per page images, four-panel grids, pages without panels where images bleed into each other and a hilarious single use of color that was the horrific (and comedic) climax of the story.

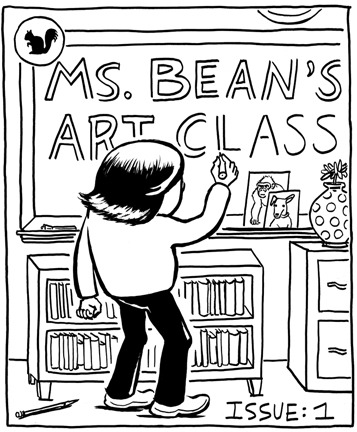

Ms. Bean's Art Class #1, is about Bean's day job as a high school art teacher. Bean's greatest strength as a storyteller is her ability to relate her students' stories on the page. There's a telling early strip called "First Day of School To-Do List" that involves being able to identify potential problem students as well as those students likely to need extra encouragement; her ability to sense what is needed for a situation seems to be a strength for Bean both as an artist and as a teacher. Indeed, this comic is all over the place visually: loosely-drawn stories with varying grid styles; illustrated text and charts; realistically-depicted figures that focus in on the intensity of their feelings; and quick drawings that get across a gag. The secret to Bean's success is her ability to wield authority in her class by way of never taking herself seriously. Every teacher wants their kids to listen, to participate and to be nice to the other kids. Instead of establishing that kind of order through fiat, she uses highly goofy humor and a willingness to be ridiculous. In these stories, it's amazing how well the students often respond to her silly sense of humor, especially because she is absolutely committed to the gag and encourages others to join in. At the same time, she also seeks to make an emotional connection with her students by encouraging their work and simply being nice to them, an approach that can help crack the most distant of students. This is an entertaining comic both because of her choices as an artist as well as her choices as a teacher.

Squeaky Noises is one of Bean's earliest comics. It's an interview between a squirrel and a rescued racing greyhound. Despite that interview format of the squirrel interviewing the dog, it's drawn in a realistic style that does well to understand the ways in which animals move and rest. It's obvious that Bean spent a lot of time drawing animals. What I look most about this comic is the restrained way that Bean attacks the sport of greyhound racing while urging people to consider adopting the animals after their racing days, when so many of them are simply put down. There are other clever storytelling conceits, like several pages of the squirrel approaching the house and jumping in (somewhat nervous about being attacked), then surprising the reader by talking. The final revelation of the squirrel being a security blanket in a very different sense is both funny and touching.

The Gremlins Movie Incident is autobio that recalls her father taking Bean and her rambunctious siblings and cousins to the movie Gremlins. Though rated PG, its grisly (if cartoonish) violence and generally dark themes made it wildly age-inappropriate for little kids, so much so that it led to the PG-13 rating. This is a funny comic, but it's also about the way the film traumatized everyone who saw it in different ways. Bean thought that gremlins would come up out of the toilet to get her and she needed company in there; her sister was afraid they'd come get her at night. In terms of the art, there are three things I especially liked. First, the way Bean draws figures as looking slightly like sausages (or at times, like beans!) is amusing, especially when she gives them big, bulging eyes. Second, her formatting is all over the map in ways that keep the reader guessing: single panel per page images, four-panel grids, pages without panels where images bleed into each other and a hilarious single use of color that was the horrific (and comedic) climax of the story.

Ms. Bean's Art Class #1, is about Bean's day job as a high school art teacher. Bean's greatest strength as a storyteller is her ability to relate her students' stories on the page. There's a telling early strip called "First Day of School To-Do List" that involves being able to identify potential problem students as well as those students likely to need extra encouragement; her ability to sense what is needed for a situation seems to be a strength for Bean both as an artist and as a teacher. Indeed, this comic is all over the place visually: loosely-drawn stories with varying grid styles; illustrated text and charts; realistically-depicted figures that focus in on the intensity of their feelings; and quick drawings that get across a gag. The secret to Bean's success is her ability to wield authority in her class by way of never taking herself seriously. Every teacher wants their kids to listen, to participate and to be nice to the other kids. Instead of establishing that kind of order through fiat, she uses highly goofy humor and a willingness to be ridiculous. In these stories, it's amazing how well the students often respond to her silly sense of humor, especially because she is absolutely committed to the gag and encourages others to join in. At the same time, she also seeks to make an emotional connection with her students by encouraging their work and simply being nice to them, an approach that can help crack the most distant of students. This is an entertaining comic both because of her choices as an artist as well as her choices as a teacher.

Squeaky Noises is one of Bean's earliest comics. It's an interview between a squirrel and a rescued racing greyhound. Despite that interview format of the squirrel interviewing the dog, it's drawn in a realistic style that does well to understand the ways in which animals move and rest. It's obvious that Bean spent a lot of time drawing animals. What I look most about this comic is the restrained way that Bean attacks the sport of greyhound racing while urging people to consider adopting the animals after their racing days, when so many of them are simply put down. There are other clever storytelling conceits, like several pages of the squirrel approaching the house and jumping in (somewhat nervous about being attacked), then surprising the reader by talking. The final revelation of the squirrel being a security blanket in a very different sense is both funny and touching.

Friday, September 20, 2013

New Versions of Old Books: Steinke, Bagge, Lafler

Let's take a look at some new collections and volumes of comics that I reviewed in their previous forms.

Big Plans: The Collected Mini-Comics and More, by Aron Nels Steinke. I reviewed the bulk of the contents of this book here and here. This collection of Steinke's early work looks great in this collection, especially his more recent stories. The earliest work looks a lot more uneven, especially in terms of the character design. The static nature of his storytelling also continues to be a distraction at times. Later in the book, Steinke makes his style work for him, incorporating beautiful and detail-oriented drawings to accentuate elements of the story in an unobtrusive way. Steinke presents himself as a figure in a permanent sense of agitation in this book, even more than he expresses anger. Indeed, he frequently holds in his anger until long after the object of his fury is out of sight and earshot. Steinke's use of interstitial pieces from short stories effectively serves to give some breathing room to the other pieces, especially since they tend to be his funnier works.All told, this book just feels like a dedicated cartoonist's first book: filled with enthusiasm, errors and a clear path of development and evolution made in public. His more recent comics about teaching really seem to be the right path for him, as he's able to merge his childlike exuberance with an adult's sense of responsibility and duty. When he collects those strips, I think we'll begin to see the fully mature phase of Steinke's career.

Everybody Is Stupid Except For Me, by Peter Bagge. In my review of the first edition of Bagge's political strips from Reason magazine, I noted that the longer pieces were more thoughtful and interesting than some of the shorter and punchier single-page strips that lacked the even-handedness of the longer stories. In this revised edition, Bagge dropped a few of those shorter strips in favor of adding longer stories, and the result is an even stronger book. Bagge is a libertarian in terms of philosophy, but is quite willing to take on Libertarian party points of view. While many think of libertarians as being gun nuts or obsessed with legalizing drugs (two points of view that show how libertarians dip into both right and left-wing ideas), Bagge's story "Brown Peril" highlights another important libertarian ideal: free and unimpeded immigration. Bagge actually does the work of a reporter and goes on the scene to political events, in this case a hispanic, pro-immigration march in Seattle. Using his quick, merciless wit, Bagge skewers those who are opposed to free immigration and reveals it as another form of othering. "Shenanigans" sees Bagge talk about the ways in which the oldest trick in politics (intimidating voters at the voting booth) was in display in Seattle when the Republican party had a schism between the old-school Mitt Romney supporters and the younger Ron Paul backers. Bagge was diligent in writing about how the backers of the other GOP candidates were in on the freeze-out at first, until they realized the Romney camp pulled a double-cross on them. Bagge really lifts the lid on the garbage pail of politics here, revealing it to be every bit as petty as one might suspect.

On a different note, I thought "Caged Warmth" was amazing. Bagge assisted a group of women in a minimum-security prison stage a musical performance by helping out with the art. The stories he tells are heart-breaking, especially when he relates his own emotions upon hearing the spoken-word testimony of one woman whose drug addiction drove a wedge between her and her children. Bagge still manages to highlight the humor of the situation while skewering his own sense of guilt in not being able to help these women, who are desperate for a letter of recommendation, a job, anything, once they are released.

The best new story t is "I.M.P.", a short biography of maverick critic and writer Isabel Mary Paterson, whose ferocity and wit made her the terror of the New York literary scene in the 1920s and 1930s. At one point a friend of Ayn Rand and a woman who was constantly amazed by the rise of technology as a way of man establishing its dominance over nature and fate, Paterson was an entirely independent thinker who owed no allegiance to any political party or system. Bagge manages to capture the essence of the historical literary figures mentioned while still maintaining his exaggerated, curvy and rubbery line and smart-ass sense of delivery. Bagge also has a knack for writing with affection about those he admires while presenting them warts 'n all. Wrapping things up with a funny strip about his relationship with Ayn Rand's works, this new edition from Fantagraphics is tremendously satisfying, even if (and perhaps especially) if one is at odds with Bagge's political beliefs.

Menage a Bughouse, by Steve Lafler. Steve Lafler was one of my earliest subjects for High-Low some years back, as I took an extended look at his Bughouse trilogy. Comparing the small print size of those comics with some of the original pages published in his Buzzard anthology, it was obvious that the Top Shelf editions looked cramped and small by comparison. This latest collection of all the Bughouse comics finally restores the series to a size that befits Lafler's character design and trippy detail. This was one of my favorite comics of the last fifteen years and a fine synthesis of Lafler's explorations into psychedelia, pulp storytelling, the world of music and the act of creation itself. It's jammed full of excellent drawing, memorable characters and a lively, joyful storytelling tone.